a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

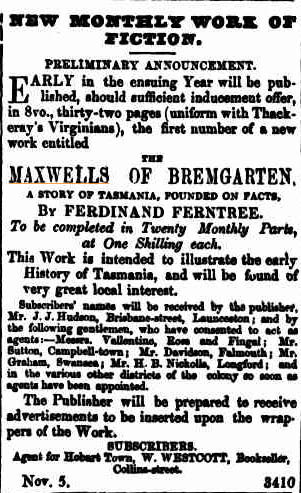

Title: The Maxwells of Bremgarten Author: William Moore Ferrar * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1403051h.html Language: English Date first posted: December 2014 Most recent update: December 2014 This eBook was produced by: Maurie Mulcahy Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Advertisement in The Courier (Hobart, Tas.), Tuesday 19 November 1858

RESPECTED READERS.—Utterly hopeless of attracting your attention in these fast days of steam, electricity, and prolific literature by attempting to explain the nature of the present work in an ordinary preface, I am induced to address you as if a tolerably good understanding were already established between us; hoping that when you finish the perusal of it, you will arrive at the conclusion that my impertinence is tolerable at least, if not justifiable.

So enlightened an individual as yourself will not require to be told that Tasmania, formerly called Van Diemen's Land, is an island lying to the south of Australia, surrounded by the Indian, Southern, and Pacific Oceans, and by Bass's Strait, which separates it from the great island continent. But with its past history—its aboriginal inhabitants, the dangers and troubles of the early pioneers of the bush, and the stirring scenes and bloody skirmishes in which many a truly valuable life has been lost, together with its present social aspects and the internal organization of its society—you cannot be supposed to be quite so well acquainted. It is true that this comparatively insignificant colony occupies a corner in many a goodly volume, wherein but very slender justice is done to its beauty, the fertility of its soil (which is not, however, universally excellent), and the generous hospitality and superior intelligence of its free settlers. That Tasmania was once a receptacle for the transgressors of British law, from wherever the British flag held dominion, is a fact which will not soon be forgotten; but it is my intention now that this island is, thanks to the liberal policy of the English nation, a free colony, to avoid as much as possible, consistently with an unbiassed narrative of the facts upon which my story is founded, this painful and delicate subject.

The island was first colonized in the year 1804, and I have purposely allowed a period of twenty years to elapse before my story commences. Even with this liberal allowance it is possible that I may be guilty of many anachronisms by bringing my family of settlers so far into the interior of the country when excellent land could be obtained at that early period within a much more reasonable distance of the capital; and when, as the late Dr. Ross informs us, the fertile vale of Bagdad, where Maxwell finds the first inland hotel and meets the hospitable farmer White, was a wilderness. Society was then in an almost totally disorganized state. The settler hurried to his location and built his wigwam without much regard for convenience and still less for taste. Here he struggled for years with difficulties, dangers, and privations which would have broken the hearts of hundreds accustomed to city luxuries from their birth. Here in the silent solitude of the bush he gradually lost the greatest portion of the refinement which he brought with him from the mother country; and here his children were generally deprived of that daily education and intercourse with strangers which unite in forming their minds for the parts they might be destined to play in the great drama of life.

A better state of things is now, however, apparent on all sides. The rude primitive wigwams have long since disappeared, and handsome cottages and well appointed mansions of timber, brick, and stone occupy their places. Excellent schools for the youth of both sexes abound in town and country. Churches and chapels raise their modest spires in every village, and ministers of religion penetrate to all inhabited parts of the island. Outrages upon life and property, though still sometimes committed, are far less numerous than they formerly were. The refinements of civilized life wage constant war with, and will, I have no doubt, a finally overcome, all habits of overbearing intolerance still to be found amongst the upper classes of landed proprietors. But notwithstanding this general explanation, it may be objected that my transition from a period of semi-barbarism to one of modern colonial comfort, not to say luxury, is so abrupt as to offend the critical judgment of those who are already acquainted with our history. Be this as it may, I can only apologize for it and for all other incongruities of style and deficiencies of construction, trusting that you will make every kind allowance for the inexperience of a writer of whose life thirty years have been passed in pursuits in which the cultivation of the belles lettres made but a sorry figure indeed.

Of the story itself I will say but little here, leaving it with no small amount of diffidence to stand or fall by its own merits. I aim at no originality of design, and am certain I deserve no credit for conceiving and successfully carrying out the ramifications of a deeply complicated plot. The narrative is based upon many undoubted truths, as a reference to the Rev. John West's elaborate History of Tasmania will satisfactorily prove. The domestic drama, with which history has nothing to do, is also founded on facts.

The scene of the story is not laid in the most beautiful part of the island, nor yet in a locality already famous for deeds of lawless violence or romantic coloring of any kind; but in the immediate neighborhood of the quiet and secluded villages of Avoca and Fingal. The picturesque Ben Lomond (about five thousand feet high) overlooks, though at some distance, the former village; while the latter, now celebrated for the auriferous quartz reefs recently discovered in its vicinity, is pleasantly situated in a valley through which runs the branch road from Campbell Town to Falmouth, on the Eastern Coast. As it approaches the sea the road suddenly dips into a remarkably beautiful glen called St. Mary's Pass, terminating in rich marshes, which are washed by the restless waves of the vast Pacific. As I rode with a friend for some miles along the beach, the angry waves foaming upon one side, and the dark mountains rising tier above tier, clothed to their summits with a dense forest, upon the other, I conceived the idea of illustrating this savage extremity of the antipodes in at least one scene of this humble history. In this, as in other cases, imagination has been drawn upon to some extent, and the result is placed in the following pages at your disposal.

With respect to the dramatis personæ, it is sufficient to observe that they are for the most part fictitious, and there are none of them intended to represent or caricature personages of real flesh and blood either dead or living. I will not assert the same, however, with respect to classes. This Maxwell may be taken as a type of the existing class of enlightened settlers—honest, courageous, and hospitable, who having commenced with small capitals and no small share of resolution, are now possessed of great wealth. Edwin Herbart may be considered to represent a large class who originally emigrated from their native land and worked themselves upward by their labor and good conduct without any capital to begin with. Earlsley is but a feebly drawn delineation of the almost despotic country magistrate, now belonging to a bygone era. Junipers and Baxters may still be met with occasionally. The names of Colonel Arthur, Jorgenson, Brady, and some others are well known to readers of colonial history; and Colonel Arnott, his son and daughter, speak for themselves.

I think myself happy in being thus permitted to appear before you. If we never meet again I shall turn—though it may be with some pain—from the great sea of literature wherein so many gallant barks have already perished, and instead of being myself the amusing and instructive author, shall seek amusement and instruction in the pages of wiser and better men.

I have the honor to be,

Respected reader,

Your obedient servant and well-wisher,

THE AUTHOR.

CHAPTER

I.—AN INTRODUCTION AND RETROSPECT.

CHAPTER II.—A

VISITOR AND A VISIT.

CHAPTER

III.—THE COLONEL'S INFORMATION.

CHAPTER

IV.—INSTRUCTIVE AND ENTERTAINING.

CHAPTER

V.—DELIBERATION AND DECISION.

CHAPTER VI.—OFF TO

TASMANIA.

CHAPTER

VII.—THE SETTLER'S FIRST JOURNEY INTO THE BUSH.

CHAPTER

VIII.—A NIGHT IN A TASMANIAN WOOD.

CHAPTER

IX.—AN ORIGINAL SETTLER AND HIS HOMESTEAD.

CHAPTER

X.—PREPARATIONS FOR A JOURNEY.

CHAPTER

XI.—OUR HEROINE'S TRAVELS AND TROUBLES BEGIN.

CHAPTER

XII.—THE JOURNEY IS CONTINUED.

CHAPTER

XIII.—FARMING OPERATIONS AND JOHNSON JUNIPER.

CHAPTER

XIV.—FARMING OPERATIONS.—ARTHUR EARLSLEY, ESQ., J.P.,

AND BAXTER THE CARRIER.

CHAPTER

XV.—GRISELDA'S GOOD FORTUNE—WINTER IN TASMANIA.

CHAPTER

XVI.—ARISTOCRATIC VISITORS.

CHAPTER

XVII.—THE SHADOW IN THE SUNLIGHT.

CHAPTER

XVIII.—PEOPLE OF THE TOWNSHIP AND MRS. EARLSLEY'S

SYMPATHY.

CHAPTER XIX.—MORE

TROUBLES.

CHAPTER

XX.—PROGRESS OF THE FIRE.

CHAPTER

XXI.—EDWIN HERBART.—EVENING AMUSEMENTS.

CHAPTER

XXII.—VISITORS.

CHAPTER XXIII.—THE

ALARM.

CHAPTER

XXIV.—A NOCTURNAL EXPEDITION.—DINNER TALK.

CHAPTER

XXV.—EVENING CONVERSATION—ANOTHER VISITOR.

CHAPTER

XXVI.—MOTHER AND DAUGHTER.

CHAPTER

XXVII.—BREAKFAST AND A TESTY COLONEL.

CHAPTER

XXVIII.—RECAPTURE OF A RUNAWAY.

CHAPTER

XXIX.—A VISIT TO SKITTLE BALL HILL.

CHAPTER

XXX.—A RUPTURE IN THE HOMESTEAD.

CHAPTER

XXXI.—EDWIN'S ADVENTURES.

CHAPTER

XXXII.—BAXTER'S PRAYERS.

CHAPTER

XXXIII.—A TENDER INTERVIEW.

CHAPTER XXXIV.—A

GLOOMY JOURNEY.

CHAPTER

XXXV.—A ROAD PARTY STATION OF OLDEN TIME.

CHAPTER

XXXVI.—EDWIN HERBART'S ADVENTURES CONTINUED.

CHAPTER XXXVII.—ARRIVAL OF ISABEL—MR. JUNIPER BEGS

LEAVE TO INTRODUCE A FRIEND.

CHAPTER

XXXVIII.—JORGEN JORGENSON.

CHAPTER XXXIX.—JORGENSON CONCLUDES HIS NARRATIVE.—A

STRANGE INCIDENT.

CHAPTER XL.—ANOTHER NIGHT IN A TASMANIAN

WOOD.—BUSHRANGERS' VENGEANCE.

CHAPTER XLI.—THE

MOUNTAIN FORTRESS.

CHAPTER

XLII.—MR. JUNIPER GETS READY FOR MRS. EARLSLEY'S

BALL.

CHAPTER

XLIII.—A SANGUINARY ENGAGEMENT.

CHAPTER

XLIV.—DULL—WHICH THE READER MAY SKIP.

CHAPTER

XLV.—DREADFUL.

CHAPTER

XLVI.—A SEAT IN MAXWELL'S HOUSE BECOMES VACANT.

CHAPTER

XLVII.—COLONEL ARTHUR'S APPEARANCE.

CHAPTER XLVIII.—A

PROPOSAL.

CHAPTER

XLIX.—FORTUNE'S FAVOR.

CHAPTER

L.—AN EPISODE IN TASMANIAN HISTORY.

CHAPTER

LI.—MAXWELL ENTERTAINS A STRANGER.

CHAPTER

LII.—EDWIN GOES TO HOBART TOWN AND MEETS WITH OLD

ACQUAINTANCES.

CHAPTER LIII.—MORE

ACQUAINTANCES.

CHAPTER LIV.—"LOVE'S

LABORS LOST."

CHAPTER

LV.—GRISELDA'S DISTRESS.

CHAPTER

LVI.—GRISELDA'S DECISION.

CHAPTER

LVII.—HENRY AND ISABEL BEHIND THE SCENES.—MR. ROUSAL'S

HISTORY.

CHAPTER LVIII.—THE

CATASTROPHE.

CHAPTER

LIX.—CONCLUSION.

EARLY in the year 18—, but we will not be particular as to dates, a large vessel, crowded with happy passengers, entered the magnificent harbor of Sydney, New South Wales. The morning was bright and clear; the sun shone in cloudless glory; and the weary voyagers, after an absence from their native land of seven tedious months, gazed with delight on the beautiful shores which on either hand sloped to the water's edge, clothed with rich verdure, and smiling under the influence of the summer's morning. To describe the exquisite scenery of this noble harbor, or to take even a passing notice of the pleasant cottages, the elegant villas, or the fairy-like gardens that adorn its shores, would be a work of magnitude to Washington Irving himself. The homely sounds of the dogs and cocks, the shouts of bullock-drivers, and the laughter of the merry children as they played beneath the wide spreading branches of ancient trees, were heard by the newly arrived wanderers with thrills of delight as the ship was being brought up to her anchorage under the skilful management of her pilot. The town of Sydney now appeared stretched out before them looking peacefully down upon the quiet waters, the abode of princely wealth, and the storehouse of plenty unaccompanied by abject and squalid poverty.

In this vessel there were many respectable families, but that of Bernard Maxwell will for the present alone engage our attention. The head of this family, which consisted of five individuals, had passed his fortieth year, and was one of those numerous stalwart sons of Britain who, arriving almost daily in Australia, were so acceptable and so necessary to that young and rapidly advancing colony. In the persons of an amiable and dearly loved wife and three young children he had given, as Lord Bacon says, "hostages to fortune." Mrs. Maxwell seemed to be in every way well suited for the toilsome life on which she was about to enter. She was possessed of comeliness but not beauty; a robust, but not masculine figure; a countenance more expressive of thoughtfulness than gaiety; and at firmness of purpose which sufficiently betrayed itself whenever an occasion arose for its display. To add to these qualities she possessed a highly cultivated taste, with a mind adorned by the countless accomplishments which shine forth with such peculiar lustre in the feminine portion of the human world.

Their children were well looking, and well made—full of vigorous health and buoyant hopes. The eldest, Griselda, had reached her fifteenth year. Her face, although not strictly beautiful, was sufficiently fair to charm the eye of the most indifferent spectator. Beneath a brow of delicate whiteness, a pair of large blue eyes looked out confidingly upon the great world. With an intelligent, as well as innocent face, of which her parents might well be proud, and a figure faultless in shape and proportion, Griselda united a voice of winning softness; indeed her mild manner was the greatest charm she possessed; and though her appearance was in every respect highly prepossessing, yet her mental qualities, just then beginning to make themselves apparent, promised to enhance its value in the highest degree. To be the perfect model of her mother, of whom she was enthusiastically fond, was Griselda's greatest ambition, for in that model she beheld a rational piety, the most perfect singleness of heart, undeviating truth, and a keen perception of the good and beautiful, wherever such were to be found.

Of her two brothers, Eugene and Charles, it is not necessary now to say much. We will content ourselves with informing the reader that they were twins, and exactly three years younger than their sister. The former was a bold and somewhat careless youth, endowed with a high spirit and many noble qualities; the latter resembled his sister in settled quietness of manner, and an apparent timidity of disposition. The children, sometimes with their parents, and frequently by themselves, walked about the streets of Sydney, examining the various articles exhibited for sale in the shop windows, and every other object of curiosity that presented itself, while their father employed himself in procuring information for his guidance to the scene of his future home.

The parents of Griselda were natives of the Emerald Isle—that pretty spot concerning which some ecstatic poet says:

There needs but self-conquest

To conquer thy fate;

Believe is thy fortune,

And rise up elate.

A little voice whispers

To will is to be

First flower of the nations—

First gem of the sea.

They were both born in Dublin, the beautiful city of whose gay streets and delightful suburbs countless recollections arise in our mind like stars of refined gold. In the midst of the varied scenery on the river Liffey, and amongst the parks, meadows, and woods adjoining its banks, the minds of Elizabeth Maxwell and her daughter were first opened to nature's primitive loveliness; and the influence thus early engendered was never forgotten by either. The father of Elizabeth was a merchant of long standing in Dublin, named Barton, who had reared a large family of sons and daughters in a highly creditable manner. Of these, Elizabeth was the youngest, but though young in years, it was generally remarked that she appeared to be more prudent and sensible than her elder sisters. However this may be, we have it on good authority that her acquaintance and subsequent marriage with Bernard Maxwell were attended by a romantic circumstance, which we may as well narrate for the amusement of our readers.

It was a gala day at the once busy but now totally neglected harbor of Howth. The naval enthusiasm of the British nation had just been raised to the highest pitch by the news of the great victory of Trafalgar, though the national sorrow was simultaneously poured forth for the hero whose brilliant life was suddenly extinguished in the hour of triumph. There was a grand regatta at Howth, and the elite of the Irish metropolis had driven out in carriages and cars to take part in the rejoicings. Crowds of fashionably dressed ladies, escorted by polite and well-looking beaux, promenaded on the quay. Military music was not wanting to heighten the pleasure of the gay company. Handsome yachts and well-manned row-boats, in some of which many of the fair sex enjoyed themselves, darted to and fro on the water; and to add to the interest of the scene, a beautiful frigate lay peacefully at anchor at some distance from the shore, an object of admiration to numerous visitors.

A fresh breeze swept over the crest of the adjacent picturesque hill of Howth, and then flew over the water towards the little island called, for what reason we know not, Ireland's Eye. About two hours after midday, after most of the cups had been sailed for and won, the guns of the frigate suddenly opened fire, and it soon became known that she was saluting his Excellency the Lord-Lieutenant, who was now seated in the frigate's state barge, half-way between the vessel and the land, the crew sitting like so many statues with their oars pointed perpendicularly to the sky. When the last gun was fired, the oars dropped with one accord into the water, and his Excellency soon found himself alongside the ship. At the same moment a boat rowed by four amateurs, in which three ladies and an elderly gentleman were seated, pulled with considerable velocity under the stern of the frigate, and this was met with equal velocity by a returning yacht which had just shot athwart the frigate's bow. The crews of both vessels seemed to have lost their presence of mind; a confusion arose, and several voices were heard shouting together. A collision took place; the three ladies in the boat screamed, and rose to their feet, and in so doing, one of them unfortunately fell into the water. The agony of the old gentleman who was evidently the father of the young lady so unpleasantly submerged, was very great; and he was on the point of plunging in after her when a loud voice from the deck of the yacht bade him stop, and another heavy splash in the water announced that that duty was being performed by somebody else. The lady remained under water for a considerable time; the brave champion dived after her like a creature to whom the sea was but a plaything, and in a few seconds brought her to the surface; in another moment she was pressed in her father's arms. As an open boat was not the most agreeable place for a lady suffering from the effects of such an accident, she was immediately taken on board the yacht, where there was a comfortable cabin. The captain of the frigate, who witnessed the whole affair, was kind enough to send an invitation to the lady and her friends to come on board, and occupy his own cabin, but this her father thought proper to decline with thanks. After being assured of the safety of his daughter, he sought out her gallant preserver, tendered him his best thanks, announced himself as Mr. Barton, a well-known merchant, and gave Mr. Bernard Maxwell, the handsome young gentleman who had displayed such well timed aquatic abilities, a cordial invitation to his suburban villa, near the charming village of Lucan—an invitation, which to say the truth, young Maxwell had often wished for, and was not slow to accept.

We will not enter into a history of their courtship, which lasted for various reasons fully two years—a pleasant time doubtless to them, as it is to all under similar circumstances. But the happy day came at length, and the honeymoon quickly passed away in travelling, and the cares as well as the solid comforts of holy wedlock commenced in due course. Maxwell retained his situation in the bank, and resided in a pretty cottage near his father-in-law's residence. Here his three children were born, and all his leisure hours were employed in opening their minds to study, and in laying the foundations of a solid education. But after the lapse of a series of years he found that the closeness of his application to the duties of his office, together with unlimited indulgence in other mental labors, began gradually to undermine his health. A partial disarrangement of his nervous system took place, and acting under the advice of a few friends, with the consent of his amiable wife, he determined to try his fortune in the still undeveloped land of Australia, to seek the restoration of his health, and to find, perhaps, an independence for his declining years.

The parting between Elizabeth Maxwell and her parents and sisters was like what such partings usually are. There were pale faces and weeping eyes. Numerous cousins and more distant relatives hung about, begging from time to time for a shake of the hand, or the still more consolatory favor of a kiss. They stood on the North Wall, on the banks of the Liffey, possibly for the last time; it was a cold but clear evening, and the bell of the steamer that was to convey them to Liverpool, the port of embarkation, rang sharply out upon the frosty air. Mr. Barton embraced his daughter and her children, and pressing the hand of his son-in-law he presented him with a considerable sum of money, and without waiting for thanks retreated precipitately into the midst of a crowd of idle gazers. At the last sad moment a youth of manly proportions and pleasing countenance advanced hastily up to the young Griselda; taking her proffered hand, he pressed his lips to hers, scarcely meeting with anything like resistance. As eaves-dropping is not generally considered a very creditable occupation, we must not presume to listen to the whispered words of parting that ensued; they were spoken amid tears and sighs; and the young Edwin hurried from the spot!

The steamer's bell rang for the last time, and the passengers hurried on board. The bow of the vessel was pushed out into the river—the paddle wheels revolved—the last adieus were spoken—and the friends on shore returned sorrowfully home.

THE voyage was more than usually monotonous, nothing having occurred to enliven its tedious length except a couple of ships spoken with at sea, and a distant glimpse of the South American coast. When Maxwell landed in Sydney he declared he had had enough of the sea to last him all his life. His health was, however, almost completely restored, and he felt as if entering upon a new existence, with a world of boundless and magnificent open before him. Mingled with his hopeful anticipations for the future were many mournful thoughts connected with the past. He had left, perhaps for ever, the dearly loved land of his birth; he had separated himself from relations and friends whom he might never see again; and had thrown up an employment of a respectable nature, to enter upon a speculation the issue of which might be extremely disastrous. He was a man of great depth of thought, and, as is generally the case with such men, was sometimes given to despondency; yet his mind was well tutored in the belief that he was under the protection of an all-wise Providence who, as it is said in the proverb, would help him if he would only help himself.

The hurry and bustle of debarkation over, a lodging procured, and the luggage safely put away, our settler bethought himself of his letters of introduction. He took one to an eminent merchant of whose urbanity and liberal disposition he had heard a great deal, and was received with politeness, tempered with a fair proportion of ice. The merchant was a keen man of business, and as his business absorbed all his thoughts as well as dreams he had no leisure to throw away upon bearers of letters of introduction; unless it was possible to drive with such bargains to personal advantage. He understood, he said listlessly, that it was Mr. Maxwell's intention to proceed into the country; he was sorry to say he knew nothing at all of the country, and could give him no information whatever. He evidently voted Maxwell's presence a bore, and bowed him out of doors with a benign smile. The settler was grieved, and making a sudden resolution never to deliver any more such letters, he packed up his remaining stock with his card in each envelope, and dropped them into the post-office.

After waiting in some anxiety for a couple of days he was pleased to find that even one out of the two dozen gentlemen to whom his letters were addressed, condescended to take some notice of him. This was a retired Indian officer, Colonel Arnott by name, who resided at a little distance from the city. He introduced himself with the honest bluntness of an old soldier, declaring that had he but known a few days sooner how Mr. Maxwell was situated he would have been on the spot to assist and advise to the best of his ability. "As it is," said the worthy old officer, "you can pack up your traps, leave them or bring them with you just as you like, and come out to my place for a few weeks until you decide what's to be done."

"You are too good, Colonel," said Mrs. Maxwell, "a family like ours would be too serious an invasion of your hospitable mansion."

"Not at all, my dear madam," said the Colonel, "if I was not sincere I'd have said nothing. I have witnessed—aye, and also suffered in—far more desperate invasions; but I came not to bore you with military tactics. My manners ma'am are like my parts of speech, or I might say words of command—short, sharp, and decisive. You'll excuse me, but my house is heartily at your service; and my wife—a good soul—will be glad to see you; my son and daughter, too, will be so happy. Fine boys those of yours sir, and your daughter a perfect lily of the valley as I live. We'll make men of those boys; which is the elder, for I see no difference?"

"This boy, Colonel," replied Maxwell, pointing to Eugene, "is exactly fifteen minutes older than his brother."

"O I see," said the Colonel with a chuckle, "That's the way to do it—nay my dear madam, no cause for blushing. Egad, I was a long time before I had even one, and then ten years before I had another, and in two years another, only three just like you; two at home, one up the country taking care of the sheep, though there could not be perhaps a more careless rascal to take care of anything."

"If you will be so good, Colonel Arnott," said Maxwell, not wishing to hear any family disclosures, "as to give me a little information relative to the mode of proceeding to be adopted, I shall feel greatly indebted to you."

"'Pon my honor, sir," answered the old officer, "you'll excuse me—but information is a thing I never do give except in my own house, and after dinner. After dinner, sir, when the ladies are good enough to show us their backs—I beg ten millions of pardons! when I crack my bottle of Burgundy as you can see by my nose, I'll give you more information than mayhap you'll be apt to relish. I'll put you up to a wrinkle or two that'll astonish you, depend on it. I am a rough old dog, sir, but I put on some restraint before the ladies; and if you don't promise to come to my house, the whole box and dice of you, I will just say this—if you ever presume to speak to me again I'll call you a sneak, if it's in the presence of the Governor. What do you say? Is it to be peace or war?"

"You cannot suppose, my dear sir," replied Maxwell, "that I am so foolish as to decline your valuable friendship; were it only for a single day I will give Mrs. Maxwell and the children the great pleasure of a drive to your residence."

"You will do no such thing, sir," said the Colonel, his carbuncled nose assuming a variety of hues, "as that is a pleasure I propose for myself. My carriage will be here precisely at eleven o'clock to-morrow morning, and if I am not in it my promising son, my second hopeful—a sly young dog, Miss Maxwell, so beware of him—will be there instead. Now pack up your things and leave the heavy articles in the charge of your landlady—an honest woman ma'am, know her very well—and be ready. You'll excuse me—have a very pressing appointment."

So saying the old gentleman shook hands with his new friends, and coming to Griselda he said slowly as if speaking to himself—"Upon my word, a delicate young flower this, rather too delicate for our hot sun; let us see—fair hair, classic forehead, blue eyes, Grecian nose, cherry lips, chin-chopper-chin," tucking her under it and laughing aloud, "Mr. Maxwell, keep your eyes on that girl. Good-by boys, we'll make men of you, we will;" and the Colonel put on his hat and walked out, striking his cane heroically on the floor.

Punctually at eleven the next day, according to the Colonel's appointment, a carriage drove up to the door, drawn by two handsome bays. From it leaped a fashionably dressed young man, rather well-looking, though of an Indian cast of countenance, with very black hair, and sparkling eyes of the same sombre hue. He was rather tall and slight, but of an exceedingly good figure. He announced himself as the son and representative of Colonel Arnott, who, he said, had been reluctantly compelled to stay at home, owing to a severe attack of gout. The young gentleman did the honors on this occasion with studied politeness, and in a short time the whole party were proceeding at a rapid pace down George-street on their way to Cook Villa, for its proprietor loved to do all in his power to perpetuate the names and fame of England's greatest men. The day was fine and not much too warm, the horses were fresh, and the road tolerably good. The party did not seem disposed for conversation, except that young Arnott would turn round in his seat beside the coachman occasionally and point out some particular place, or the residence of some noted man to Mr. Maxwell. The young people enjoyed their drive; Mrs. Maxwell and her daughter looked perfect pictures of happiness, while Maxwell examined with care the many objects of beauty that passed before his eyes, though his mind was not yet divested of that anxiety for the future which he could not altogether shake off. Arriving at the summit of an eminence from which a commanding view of one of the most splendid harbors in the world can be obtained, Mr. Arnott ordered the carriage to be stopped in order to afford the newly-arrived family an opportunity of examining the scenes that lay on either hand—exquisite panoramas, not easily forgotten when once gazed upon. On the left they could see the city of Sydney with its white arms jutting out into the bay, and looking peacefully happy as hundreds of suburban cottages reflected the beams of the midday sun, with the curved and jagged outlines of the harbor, its bays and islets, unrivalled in the beauty of its quiet waters, and the welcome haven of many a weary mariner. On the right a less beautiful but more rural picture presented itself. A vale of great extent was spread out before them, in the midst of which a sheet of water like a quiet river or lake lay surrounded by beautiful knolls, clothed with underwood and adorned with trees of patriarchal dignity.

When these enchanting prospects had been sufficiently admired, the carriage moved on, and in a little time entered a broad gateway, at which hung a wooden gate painted red. They were now within Colonel Arnott's domain, which, about fifty acres in extent, surrounded his house and offices. The avenue was rugged, being in an unfinished state; the holes were partially filled up with stones newly gathered from the soil, so that our travellers were glad when their journey was over. At the door of an aristocratic cottage orneé they found their loquacious host standing, one of his feet encased in a polished boot, the other wrapped in numerous cloths and bandages, supporting himself with a stout stick. Advancing cautiously as the carriage drove up, he lifted his hat with a gallant air, and said in a loud voice, "Welcome, welcome to Cook Villa, my dear madam! How d'ye do, Maxwell! Haven't forgotten your name, you see. Welcome, my future heroes. Ha, my fair lily of the valley! Powers of lightning! Mrs. Arnott, ma'am, where are you!"

"I am happy to see Mrs. Maxwell," said a female voice; and a tall, dark-haired lady, moving with majestic grace, came forward and presented her hand. "I bid you welcome to our land of sunshine. Pray come in; I hope these hot summers will agree with you better than they do with me."

The busy Colonel introduced Maxwell to Mrs. Arnott; also, Miss Griselda Maxwell, and Masters Romulus and Remus Maxwell. Mrs. Arnott smiled, saying, "O, Colonel, you are surely joking;" to which he replied, "Not a bit, 'pon honor."

A young lady now came forth. "O, Isabel," said Mrs. Arnott, "Mrs. Maxwell, allow me to introduce my daughter; Miss Maxwell, my daughter Isabel."

The party entered the parlor, and took seats, the Colonel making facetious remarks and complimentary speeches; when after sitting about five minutes the ladies rose by general consent and left the room, Mrs. Arnott having invited her visitors to take off their bonnets. Contrary to expectation Mrs. Maxwell found in the Colonel's wife a lady-like woman in the prime of life. Her deportment was stately, and her manners tinged with a slight shade of hauteur, the result, perhaps, of an over-strained consciousness of superiority of blood and birth. On the present occasion, however, she seemed desirous of making a favorable impression. Her features were pleasing and regular, but sharp, and expressive of great shrewdness. Her hair and eyes were black, like those of her son and daughter. This last was a sprightly damsel of seventeen, with some pretensions to beauty: her dark complexion and elegant figure were both alike faultless. She was dressed in white, with a blue kerchief on her neck fastened by a showy diamond brooch.

The Colonel and his residence remain to be described. The imaginative reader may picture to himself a short, straight, puffy old gentleman with capacious checks and purple nose. His eyes, which twinkled and sparkled incessantly, were of a dark hazel hue, and a few thin locks of very white hair peeped from beneath a high crowned white hat, which when removed displayed a shining bald head, extremely venerable in its antiquated appearance. He wore a loose morning wrapper of yellow silk, a white waistcoat, and dark inexpressibles. His perpendicular figure was displayed in a pompous strut and magisterial air.

The residence, built doubtless on the proprietor's own plan, after the fashion of a Bengal bungalow, was constructed principally of wood. It covered a large portion of ground, and had a verandah in front and at the sides. The dining and drawing-rooms, principal bedrooms, and kitchen, were all on the ground floor; and there was plenty of space for the Colonel's family and visitors. The offices consisted of a spacious stable, in which four horses were well kept; and amongst numerous etceteras a well-stocked aviary occupied a genial corner, enjoying alternately sun and shade. The garden was large and quite full of flowering shrubs and fruit trees, amongst which the orange, apricot, peach, and mulberry were conspicuous. There was a little lawn sloping away to the margin of the bay, and a paddock wherein a couple of contented cows roamed at pleasure.

It was now two o'clock, the Colonel's usual hour for dinner, and a bell was rung to announce the important fact. In a few minutes the company assembled in the drawing-room, and the host pompously conducted Mrs. Maxwell to the dining-room, Mr. Maxwell performing the same act of politeness for Mrs. Arnott; Mr. Henry followed with Griselda and his sister, the two boys bringing up the rear.

The conversation scarcely lagged for a moment, the Colonel's jokes and hearty laughs were frequent, and the rest of the party partook of his gaiety.

"Your daughter," said Mrs. Arnott to Mrs. Maxwell, "has a very uncommon name. Griselda I think you call her."

"That is my daughter's name," replied Mrs. Maxwell.

"Well, I think it is a delightfully pretty name, so very singular."

"I think it's an infernally ugly name," said the Colonel.

"O Colonel," said his wife, "how very shocking! You will make use of those barbarous words, though you know they annoy me so much: pray Mrs. Maxwell do not mind him—his expressions sometimes quite put me to the blush."

"Like the tip of my nose," said the Colonel.

"O for shame you dreadful man," said Mrs. Arnott, using her smelling bottle.

"Well, well," said the Colonel, "we won't quarrel about names. A rose you know by any other name, etcetera—your good health fair lily of the valley; if your name is ugly you are not, at least if my eyes are as good now as they were fifty years ago. Your mamma will now tell us, my pretty one, why you were called by such a greasy name—it sounds to me like that of a Spanish gipsy."

"I will tell you with pleasure," said Mrs. Maxwell. "You have doubtless heard of Madam Steevens's hospital in Dublin?"

"No, never in my life ma'am."

"Well, you must know that there is an hospital so-called in that city, and it derived its name from the fact of a lady of rank and fortune having shut herself up within its walls, and devoted all her time and money to the amelioration of the sufferings of her poor and diseased fellow creatures. The lady's name was Griselda Steevens. Her brother, Dr. Richard Steevens, was a man of considerable fortune, and when on his death bed he called his sister to him, and asked her if it was her intention to marry, if she thought of so doing he would leave her all his fortune without reserve; but if not, he would leave it to her for her life only, and after her decease to found and endow an hospital. She, with an abnegation of self worthy of the highest honor, promised him that she would never marry, and he made his will accordingly. She not only kept her word, but immediately commenced carrying her brother's intentions into effect, without wishing to enjoy his fortune in any other way, and when the hospital was ready for her reception she fixed upon it as her own permanent residence. My mother was a very intimate friend of this lady, and, indeed, it was at her request that I called my daughter Griselda, with Mr. Maxwell's concurrence, of course."

"Of course," said the Colonel, "but upon my honor a very pretty little story, quite a sunny episode in our dark and hard-hearted world; but, sounds! Mrs. Arnott, ma'am, you're not going so soon? Well au revoir, as the poet says—

Fare thee well, and if for ever,

Still for ever, fare thee well.

Harry, you young dog, why don't you open the door? You look at Miss Maxwell as if you never saw a young lady before—be quick you planet struck son of a Fort William fire-eater."

Mrs. Arnott, without deigning to take any notice of her husband's speech, gracefully swept out of the room, followed by Mrs. Maxwell and the young ladies; while the Colonel stood up, rubbed his hands, and chuckled audibly.

"Shut the door Harry—and now Maxwell for a little bit of pleasant chat; draw your chair closer, I want to hear what you say distinctly, not that I am deaf either, but fill your glass and pass the decanter this way: I always take an hour after dinner to assist digestion; I drink half a bottle of Burgundy no more and no less—or if I can't get that, good old port or claret will do as well—excuse me for talking so much about number one, but if we don't mind number one who will mind it for us sir, except to send us to the dogs?" saying which the old gentleman laughed complacently and drank his wine, as if his opinion of himself was good and his balance at the bank ditto.

"I trust, Colonel," said his guest, "that your time for giving information on colonial matters is fully come, if not, to-morrow will do quite as well."

"I am not a procrastinating man sir," replied the Colonel; "by the by those two heroes of yours may go into the garden or into the verandah—if you see a snake my juvenile Castor and Pollux you may catch him by the tail, but mind you cut off his head first."

Eugene laughed as he rose and said, "From such an enemy, Sir, I would sooner run a mile than fight with a minute."

"Ah! very good," said the Colonel, "you're a smart boy, we'll make something of you I see—good-by for the present. Now, Mr. Maxwell, what do you propose doing?"

"That depends, Sir, on the advice I may receive; I am completely and profoundly ignorant of everything connected with this country."

"Well, Sir, it was my own case once, but with the aid of a head-piece pretty properly screwed on I soon surmounted the difficulties of ignorance; I became master of as much information in a fortnight as you would probably obtain in a year, and how do you think I did it? I put half a dozen advertisements in the papers here—we had not many papers here ten years ago—one for a situation in a merchant's office or bank, another as from a merchant very much requiring a clerk, another as from a gentleman urgently desiring to purchase a sheep or cattle station up near the Blue Mountains, and so on, all particulars to be forwarded and localities described with precision. In about a fortnight, Sir, I was master of a great store of information. I found that the merchants wanted a few trustworthy clerks, that there were no clerks, except prisoners, to be had for love or money; and I received about a score of letters from proprietors of sheep stations, written in such flowery language, and describing the hills here and the vales there, the rivers, the sweet lagoons, the distressingly fat sheep, and the cattle not able to wag their tails; so that I felt myself like a regular ass shut up in a paddock along with a forest of haystacks; whereupon I wrote home to my poor relatives to tell them to come out if they wanted situations as clerks, and toddled away to look at some of the stations in the country. I was not long in making up my mind, Sir. I am a man of some decision of character. I soon selected a station with 5000 sheep and 500 head of cattle; terms made easy—one-fifth of the purchase-money paid down, remainder in five years. Got on like a regular old fighting cock. Sent ten thousand sheep across the Blue Mountains, have forty thousand now, besides lots of rhino."

Here the Colonel paused to take breath, and tossed off a glass of wine.

"Fill your glass, sir, and pass the bottle to Harry."

"No more thank you," said Maxwell.

"Ah, you're a moderate man I see; well I've nearly finished my daily allowance. How much tin have you got? Excuse my impudence."

"If you mean money, Sir, I can muster something over two thousand pounds."

"A respectable sum," said the Colonel, "a very respectable sum, Sir, for this place; a handsome start for either town or country. If you like to set up in business as a merchant or shopkeeper there are plenty of openings; business is increasing, and will increase. If on the other hand you prefer a country life, there's plenty of room, go up the country—call on my son and commanding officer, Mr. Frederick Arthur Wellington Arnott, and he'll put you in the way of everything—buy your station—come down again—take wife and children up—sit down comfortably, light your fire in blessed ignorance in the bush and burn yourself out, house, sheep, dogs, and all before you've been there a month."

The jolly old Colonel laughed but Maxwell looked grave.

"Mr. Maxwell," said Henry, who had not spoken since the ladies left the room, "had better go and have a look at the country, and I will cheerfully go with him—it is my opinion——"

"Well by the ghosts of St. George and the Dragon!" broke in his father with real or pretended wrath, "you are a precious example of modern school teaching. Who the deuce asked you for your opinion, sir? What on earth do you know about it, sir? You want to have all the talk to yourself. If you want to chatter go join the ladies, and they'll give you enough of it. There never was a man, Maxwell, surrounded by such a set of geese; if I listened to the advice that this fool is continually poking into my ears I'd be buried fathoms deep in the Insolvent Court, a miserable prey to the scoundrels and robbers of the law."

"Well," said Henry, "I only meant to say——"

"'Pon my honor," again interrupted the old gentleman, "if I thought you were going to talk sense I would listen to you. You amuse me very much. I like an upright specimen of the coolest impudence in the world. When I was a young fellow I served under my uncle along with Wellesley in India, and fought under the walls and in the streets of Seringapatam, and in the middle of the row while running pellmell alongside of the old man—my uncle, I mean—I saw our lads catch hold of the villain Tippoo and shouted, 'They've got him, uncle; they've got him!' 'What, talking again, you blackguard!' roared my uncle, and he caught me by the collar and kicked me, Sir, till the blood spouted out of my nose like a stream from a cask of canary. That was discipline if you like, Maxwell."

"I should not like it, Sir," said that gentleman, laughing.

"And if your uncle, Sir," said Henry, determined to be heard, "was then anything like what you are now, I am not surprised at the sudden retreat of the enemy. Besides, it is scarcely thirty years since that happened; you are now past seventy, and you don't mean to tell us that your uncle kicked you in the streets of Seringapatam when you were forty years of age?"

"Hold your impertinent tongue, sir; if he didn't kick me, he kicked a drum boy that was next me—my memory is sometimes defective, and I know somebody was kicked but we have had quite enough of your talk, sir, quite enough of your talk; go and sing a duet with your sister for the amusement of our female guests, and leave Mr. Maxwell to learn a little wisdom from a man capable of teaching him. Chop my old carcase into mincemeat for bombshells! but the service is coming to a pretty pass."

The wrathful Colonel tossed off another glass of wine, while his son, not caring to provoke further hostility, rose with a careless air and left the room.

"That's the way I serve the jackanapes," said the host, after delivering himself of a few short coughs; "he wants to have everything his own way, but he sha'nt; he's like his mother, and she's like the rest of the feminines—give them an inch of authority and they'll take miles; if you want to make your sons, sir, cold, heartless, and selfish, give them unlimited power and authority over all your property, over yourself, their mother, and sisters, and you'll be astonished how very soon you'll find yourself in a dog kennel."

"Pardon me, Colonel," said Maxwell, "but are you not afraid of seriously offending your son? It is written, 'Fathers provoke not your children to wrath.'"

"O, leave him alone! he's no such fool, neither; he knows I keep the bone in my hand, and follows like any other dog. I like to keep him in order. If I didn't keep him in order I should sink down to nothing at once, for he knows how to rule his mother, and she is of such a commanding disposition—though she's a good soul—that she would soon rule me, and everything would go to the dogs. It takes the likes of me, sir, to rule them all."

"You have another son in the country, sir?"

"Yes, sir, my eldest son Frederick is ten years older than this youngster; his mother, one of the fairest and best women that ever walked in Calcutta, has been in her grave now, poor thing, for eight and twenty years. Do you know, Maxwell,"—and here the speaker's voice wavered a little—"that your fair daughter is the born image of what my lost Henrietta was when she arrived from England with her father the General, and I carried her off in triumph from a hundred competitors, while seven-eights of the bachelor officers of the garrison swore that they'd run me through the body. She had such blue eyes and such fair hair. She used to say—'Harry, you're a clever man, you're too clever, you won't live very long,'—but she was mistaken, it requires a man to be clever to live very long in this world. You see young men who think themselves such wiseacres bustling about and trying to put old men like me down into corners, dying miserably by scores before they're fifty years of age; while here I am nearly eighty, never troubled myself about anything, laughed at everything, was always ready, Sir, to sing my song and dance my hornpipe. I sit here as independent as the chief of the Chocktaw. Frederick manages the sheep, pay him five hundred a year, I receive the wool and tallow, transact all the town business, and make myself as comfortable as an old horse in a clover paddock."

"Have you ever been to Tasmania* Colonel?"

[* This modern designation of the island is adopted in this work. Its former appellation of Van Diemen's Land is, for variety of reasons, suppressed.]

"Yes I have been in Hobart Town, the capital of the island, but never in the country; they say it's a fine country, well grassed and well watered. Have you any idea of going there?"

"I have been advised to go there; I have heard that the Government gives grants of land to bona fide settlers, according to the capital and property they possess."

"That is quite true, Sir, so they do; but I see they are talking already of annulling those regulations. If you think about going there I'd advise you to be quick."

"Have you any idea how much land they would be likely to give me?"

"Well, I think they would give you a maximum grant; that amounts to two thousand five hundred and sixty acres—four square miles."

"Why, bless me, Sir, that would be a splendid estate—a fortune for life. If I had that I would surely be satisfied for the rest of my existence."

"I shouldn't like to swear to that; you know the saying—Have much, want more. I suppose you're a man like the rest of mankind; there are not many exceptions to the general rule."

"I think," said Maxwell, "that a man ought to be satisfied when he is conscious of having enough. A farm, for instance, that supplies all his wants and the wants of his family, that produces for him in return for his labor plenty of food and raw material convertible into cash to pay for other necessaries of life or the education of his children—a man so happily situated should be thankful to God, and not be so extremely weak as to be perpetually panting for more."

"So he should, Sir, so he should, I quite agree with you," said the Colonel, "and doubtless many are so, but there are others who, always ready to carry covetousness out fully in all its branches, would without remorse kick every body into the fiery crater of Mount Aetna, and then go home, smoke their cigars, drink their brandy and water, and feel as comfortable as possible."

"Are such men numerous in Tasmania, Sir?"

"Don't know—never saw one in Hobart Town. That is a nice place, and there are nice people in it. I have enjoyed their hospitality till it nearly killed me."

"Pray, my dear Sir, will you allow me to ask you whether if you were about to commence life again in these colonies with your present large stock of experience, you would do as you have done or prefer going to Tasmania, with the prospect of obtaining a maximum grant of land?"

"It is a difficult question, Sir," answered the old officer, wiping his forehead, "and in order to give a satisfactory answer it will be necessary for me to sound the bugle and parade all my available ideas. If Harry was here now he could help me a little. Well, in the first place I am a terrible fellow to be attracted by difficulties. If I hear of a place distracted by murders, robberies, arsons, devastated by floods or overrun by bloodthirsty enemies, my anxiety to go and pitch my tent there becomes intense. I am too old now or you wouldn't find me here with one foot on a chair and the other under my dinner table, while there's work to be done in any part of the British Empire. My penchant for difficulties has often led me into serious troubles, but the greater the troubles the fonder I grew of them. His grace the Duke of Wellington when commanding at the battle of Assaye did me the high honor to take notice of this. I was exhausted by the hardest fighting imaginable, and most of my men were lying on the ground waiting for orders, for they were tired, poor fellows, and took that opportunity to rest themselves a bit, and I was just taking a little sip out of a lemonade bottle that I had hastily stuffed into my breast when who should come riding up but General Wellesley, for he was not a Duke then—'Captain Arnott' says he, 'you're the very man, the bravest on this field—take your company quickly and assist Colonel Viccars'—you know Viccars who gave you your letter to me—'in storming that four-gun battery which is raking our left.' 'Sir,' said I, 'your penetration does you infinite credit;' and in a moment we were in full charge, shouting like devils, with British cheer and British bayonet, and away went the enemy scampering and tripping one another's heels up. I ran fifteen of the rascals through the body while you would be saying 'think about it,' and attacked their scoundrel of a captain, sword in hand, before he had time to go to the right about, when just as I was going to assist him in kicking the bucket, up comes a great hulking fellow of a grenadier and knocked my sword clean out of my fingers, when on him I turned, sir, like a hungry panther, and if I didn't smash his face right in with my bottle, and make him a present of the rest of my lemonade, you may call me a snivelling poltroon this blessed minute."

"That was a lucky bottle," said Maxwell, edgewise.

"It was, sir," continued the eloquent old gentleman, "it was a lucky bottle. But to the question: you asked me, I think, whether I would not prefer a million of acres in Tasmania to ten thousand here—no, I beg pardon, that was'nt it; you said something about a maximum grant—certainly I would prefer a maximum grant to no grant at all; I would even prefer a minimum grant to no grant at all, but—you'll excuse me I really forget what the exact nature of your question was."

Maxwell, though rather fatigued with the pertinacious loquacity of his host, repeated his question.

"O yes, certainly," said the Colonel, "yes, I knew I had got adrift a little—I understand—I certainly would prefer staying here provided they would give me the grant of land, but as they are not likely to do that I would rather go to Tasmania and get one; that is if, keeping my property here, mind you, I could pass myself off as a bona fide settler from England with only two thousand pounds in my pocket, instead of a New South Wales colonist with twenty or thirty thousand—which I believe would be conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman. I really hardly know how to advise you, Maxwell, but if I were in your place, I think I would make a bold push for the grant of land; and when you are well established on it send one of your sons over here, or both, and buy a station where there is plenty of room."

"And very judicious advice I think it is too, Sir," replied his guest.

"Well, Sir, I am glad you think so. I merely mention these matters; you can act as you think proper. If you like to take a run up to my station, you are heartily welcome. Harry says he'll go with you—would go myself, but you see what an old cripple I am. As it is, we'll take care of your wife and children till you come back again. Now, I should like very much to go for the sake of the difficulties to be encountered on the road—sleeping in the open air where there's not a house within dozens of miles, and waking up perhaps with a black snake across my throat by way of a muffler—or crossing rivers up to my chin, or waiting for weeks before they can be crossed at all. And then, Sir, if you're fond of horse exercise, as most of your countrymen are, my son, Arthur Wellington, will select for you a noble specimen of horse-flesh that he calls 'Donnybrook,' which noble beast will condescend to let you mount upon his back after you have lost an hour trying to do it, and when you are well up he'll carry you playfully to the nearest gum tree and then set up his back like a miniature rainbow and pitch you right over it, branches and all. The last time I was up there, this excellent son of mine (not Harry, but 'tother fellow), who thought I didn't know anything about it, called out loud enough to be heard a mile off to a grinning vagabond of a hut keeper, 'Bring up Donnybrook for my father to ride.' Well, I said nothing aloud, but thought, 'This fellow thinks himself one of the cleverest and clearest-headed chaps and the best manager in all the Australian, but I'll astonish his weak nerves.' Presently up comes the monkey-faced hound leading the brute by the bridle, and keeping his head turned away to prevent me twigging his laugh, while I quietly pulled out a small pistol and saw that it was properly primed. 'Is that Donnybrook?' said I to the man, 'Yes, Sir' said he, 'he's a very quiet beast I believe!' says I. 'Oh, he's middling for that Sir, but you'll be able to manage him,' says the rogue scarcely able to keep himself from laughing in my face. 'Take the saddle off, Sir,' said I in a tone that stopped his laugh at once: it was done—'take the bridle off;' that was done. 'Now you fat thief off you go,' said I, with a roar like a clap of thunder, and away he flew kicking up his heels and after him flew my pistol bullet whizzing into his beef, Sir, like a red-hot bayonet into a bladder of lard; and then I turned upon Frederick—'You're a pretty fellow,' said I, 'you got that beast up here in the hope that he would break my old neck, but you're deceived, Sir, you're deceived this time—you shan't handle the property so soon, Sir, I promise you.' Whereupon Fred began to talk and I began to swear, and we had such a delicious row, you never heard the like of it."

Maxwell rose from the table saying the ladies would wonder what detained them so long.

"Yes," said the Colonel, "I will now take my siesta—always take an hour's nap after dinner, if you like to follow my example there's the sofa, and I dare say no one will disturb you—will meet you in the drawing-room in about that time."

The Colonel retired to his private apartment, and his guest, who was not inclined for sleep, proceeded in search of the ladies.

Guided by the sound of music, for which he always possessed a willing ear, Maxwell entered the drawing-room situated at one end of the building and connected by a long passage with an abrupt turn or two in it with the one he had just left. This apartment was furnished with the greatest care, and wore an aspect of elegance conferred on it by feminine taste and ability. The furniture was light but of exquisite workmanship and costly materials. It was refreshing to Maxwell to sit down upon a sofa and find himself gradually settling within a few inches of the floor, so soft was the luxurious cushion; and the more so as he had been only just released from his confined cabin on shipboard after an incarceration of seven months. Here in pleasant languor he sat for awhile, his eyes wandering from picture to picture on the walls; from the rich ornaments of the mantelpiece to the table covered with handsomely bound books, and to the attractive carpet under his feet. "A happy man I shall be," said he to himself, "if at fifty years of age I can call a room like this my own, and sit listening to my daughter's music." It was not his daughter, however, who sat at the pianoforte but Miss Arnott, already introduced to the reader by the euphonious name of Isabel. She played a lively air, ever and anon turning her graceful head, clothed with a flowing profusion of coal black ringlets, to smile upon Griselda, who sat a little behind but near her, and exchange some little particles of innocent chat. The marked contrast between the complexions and apparent dispositions of these two young ladies could not fail to strike any cursory observer. The one fair almost to a fault, and timid as a young antelope upon its native precipice; the other dark in an equal proportion, with eyes so penetrating that one could not hope to escape their piercing lustre. And yet there seemed to be already a growing sympathy between them—a sympathy, as it were, between dark night and sunny day—the result perhaps of some secret desire frequently implanted in the human breast, which leads many of us to admire in others those qualities in which we find ourselves deficient. Eugene and Charles were seated near the table looking over amusing books, while the absence of Mrs. Arnott, Mrs. Maxwell, and Henry told plainly that they had not risen from their respective siestas.

Maxwell was absorbed in thought, to which the music rising and falling rapidly upon his ear lent a most singular charm. A delightful vision of future independence, if not wealth, and the consummation of all his earthly happiness, wandered through his brain. At one moment he fancied himself the possessor of the million of acres so feelingly alluded to by his lively host; at another he thought that if he could only obtain a maximum grant how comfortable and how well situated he would be for the remainder of his life. His wife, too, to whom he was fondly attached—why should she not share his pleasing dreams? Awaking from his reverie he hastily asked Griselda where her mother was. His daughter was about to reply when the two matrons suddenly entered the room.

"The afternoon is now sufficiently cool," said Mrs. Arnott; "what say you, Mr. Maxwell, to a short walk in the garden or about the grounds?"

"I shall be most happy to place myself at your disposal," replied that gentleman.

"Very well," said Mrs. Arnott; "my dears, will you accompany us, or remain here?"

The young ladies intimated their willingness to be of the party, and Maxwell, placing himself between Mrs. Arnott and his wife, led the way.

It was now six o'clock. The sun was approaching the rim of the western horizon, and being enveloped in light clouds of purple and golden colors, with a dim haze-like smoke, perhaps from some distant fire, shed a bright orange glow over the broad bay and surrounding hills. A fresh breeze, bearing on its bosom the delightful fragrance of many an exotic shrub and flower, swept through the garden and over the pleasant fields. Birds of the gayest plumage, and winged insects arrayed in countless brilliant hues, awoke from their drowsy lethargy and sported on the evening air; while from the surface of the smooth water the rays of the declining orb were reflected as from a lake of burnished silver. Griselda paused to gaze upon the charming landscape, and while so doing her heart bounded with love and gratitude to the Creator of all, who had permitted her to look upon and enjoy such a scene. From a pleasant train of thought she was aroused by the voice of Miss Arnott calling her to come and see her pretty birds indulging in their evening play.

"Call me Griselda," said she, smiling, and taking her companion's arm.

"Oh! certainly, and you must call me Isabel."

"Nay," replied Griselda, "I feel as if I could not; you are so many years my senior."

"Only one or two," said Isabel; "but what matter—I insist upon it, and so you must. Now look at my birds. Oh! I declare, there's my little prince of bower-birds on the floor holding down his pretty head. What is the matter, Princie? Have they been beating you, my poor little fellow? He is not well. These bower-birds, Griselda, are the most interesting creatures you ever saw; they build such pretty bowers for themselves, and play so nicely; you must try and see them at work in the morning. You admire my large collection of beautiful parrots and cockatoos. There is a very fine specimen of Dacela Gigantio, or laughing jackass. That is the Menura Superba—that splendid bird with its tail something like a lyre. We have also the honey-sucker, belonging to the family of the Meliphagidæ. Goodness, gracious! who is that? Oh! Harry, how you frightened me."

"Serve you right, you minx," said Harry, with a laugh, "when I find you here puzzling Miss Maxwell's poor head with your abominable jaw-breaking names. The Latinized monstrosities of your birds and mother's plants ought to be twisted into a hard rope, and you and she tied together with it."

"And to please your dictatorial lordship we ought to be thrown into the middle of the bay, too, I suppose?" said Isabel.

"Nay, you need not ruffle your feathers so. I am a plain young man, and do not require sauce after dinner," answered the brother.

"Because you have got enough already, if we are to judge by the haste with which you ran away from papa," replied the sister.

"A very pretty retort-courteous, upon my honor. Miss Maxwell must be delighted at such exuberant wit," said the gentleman.

"If you do not cease, Sir, I will lay the whole case before papa this instant, and he may treat you to a little pepper as well as sauce," retorted the lady.

"O dear! how wild we are getting. But come, make it up, and I will take you and Miss Maxwell out in my boat to-morrow for a pleasant row," said Harry.

"You must learn to behave yourself like a gentleman before either of us will condescend to step into your boat, or even to walk by your side," said Isabel, a little mollified.

"I'll conduct myself like a nobleman," replied her brother. "Will Miss Maxwell, allow me the pleasure of showing her round a the garden?"

He offered his arm politely, but Griselda preferred taking that of Isabel.

"Well," said he, "proceed—I will follow like a footman."

In this order they entered the garden, a large well-fenced piece of ground, stocked not only with the European fruit-bearing trees and shrubs which flourish in the genial climate of New South Wales, but also with a many rare plants selected with care from the extensive flora of Australia. Nor was Mrs. Arnott's fondness for botany confined to Australian productions alone. She could boast of having in her conservatory many a rare exotic from the islands of the Pacific—from Java, Borneo, and New Zealand. Our acquaintance, Harry, still keeping close to the young ladies, had not been in the garden more than a few minutes when he suddenly exclaimed—"Do you hear that? mother's at the jawbreakers already! Well I'm off—good-by, ladies."

"O, good-by! by all means," said Isabel. "Come, Griselda, we will go and hear what Mamma is saying."

"Well, my dears," said Mrs. Arnott, whose maternal solicitude was pretty constantly awake, "you are, I trust, improving the passing hour by examining with care the beautiful productions of nature with which you are surrounded. This tree, Mr. Maxwell, is a young specimen of the extensive genus Eucalyptus with which our country is completely stocked; it is vulgarly called blue gum, and sheds its bark instead of leaves, as indeed all the different species do. I have a great number of them, which will in time make our place look like a forest. This is another, but of a different species, the Eucalyptus Corymbosa, or blood-wood tree. This pretty shrub, laden with such a quantity of yellow blossoms, is the Acacia Pubescens, quite common here, but new to a stranger from England. I can show you a few more individuals belonging to the order Leguminosa—for instance, we have the Acacia Melanoxylon, or blackwood from Tasmania; likewise the Acacia Sophoræ, or Fragrant Acacia, though it scarcely looks well, as we are rather too far north; when in full bloom it is really lovely; and in addition to these we have the Acacia Longifolia, or Long-leaved Acacia—its short, spiked flowers are very pretty. This umbrageous, bower-like tree is the Corypha Australis, which with the Seaforthia palms, weeping casuarinas, and myrtaceous plants, give quite a singular appearance to the great forests in the interior. This beautiful climbing flower is the Teconia Australis, you see in what rich clusters the petals hang suspended; and we have an interminable variety of umbelliferous, decandrous, papilionaceous bushes, bearing flowers of most brilliant colors, as also——"

"Please, ma'am," said a servant running up out of breath, "my master is getting anxious for his tea."

Recalled by this vulgar message from the Elysian fields of science in which her well stored mind was disporting itself, Mrs. Arnott conducted her friends back to the house. They found the Colonel seated in his snug arm chair, and the tea things laid in the dining-room. He immediately addressed his wife with a slight degree of asperity, saying—"What in the name of engines of war not yet invented, Mrs. Arnott, ma'am, keeps you out so late? I've been waiting an hour."

"I have been showing our friends our garden treasures, Colonel," answered the lady. "You need not be so impatient—I never disturb you in your after-dinner chit-chat."

"You keep me here dying of thirst, ma'am," interrupted the Colonel, "so that I had a great mind to go and take a swim in the bay. Talking of swimming, Maxwell, I once met with a queer adventure that I'll just tell you of while the tea is getting ready. I was once, Sir, as green as duckweed, up the country in very hot weather, and taking a quiet walk along the banks of a river near a friend's house where I was staying for a few days, when the idea occurred to me to pull off my duds and have a swim. Well, Sir, I sat down on the bank, and commenced leisurely to unscrew my coat and unmentionables, when I heard a measured treading thump, thump—just behind me; I turned round without making any noise, and what do you think I saw? A buck forester kangaroo, Sir, about seven feet high without b—- s—-, standing bolt upright about thirty yards off and staring at me just as if I was something good to eat. 'O ho!' said I, 'just wait there my gentleman, 'till I get my bulldog out will you, but I was afraid to move for fear of scaring the rascal the wrong way, when—power o' mercy—he came a half dozen jumps nearer and pawed the air like a perpendicular racehorse, so I just quietly touched the trigger of my barker—I never travel without a pair—and down he came for all the world like a sack of potatoes out of a hayloft. Well, Sir, I went and examined him and found him stone dead to be sure, but he was a fine animal and I thought it singular that he should have a piece of blue ribbon tied round his neck. So I went in and had my swim and went home to my friend's house, and whom should I meet on the way but Mrs. Blackmore, the lady, looking about for something very anxiously."

'O! Colonel Arnott,' said she, 'I have lost my poor Rolla—did you see him?' and she called 'Rolla! Rolla!'

'Who the dev—hem—I beg pardon—but who is Rolla, ma'am, if it's a fair question?'

'My poor pet forester kangaroo, don't you know Rolla?' she replied with an uneasy smile.

'Yes, ma'am, I saw a strange looking animal down near the river, and when we saw one another he bolted one road and I cut my stick the opposite.' So away she went calling Rolla, and away I went, packed up my carpet bag, left two of my best shirts in the hands of the washerwoman, called for my horse, and rode away as the fellow did long ago from the Baron of Mowbray's gate without ever once looking behind me.'

The Colonel laughed as usual and Maxwell laughed, not so much at the anecdote itself or the wry faces and comic gesticulations of his jolly host, as to please and encourage him, if anything was required to do so. Griselda and her brothers looked astonished, and Mrs. Maxwell after listening gravely said——

"The poor pet then met with a sudden and violent death—did you ever hear how the lady bore her loss?"

"The only communication I ever received on the subject was, madam, a letter from her husband saying that if I had shot the kangaroo through malicious design he would be most happy to meet me on equal terms, and then I might have the pleasure of shooting him; I replied that it was through accident of course, and that having unfortunately deprived the lady of one pet, I had not the slightest wish to rob her of another, so I purchased the richest dress and the purest pearl broach I could find in Sydney and sent them to my fair friend, by way of making the amende honorable, and never heard anything of the matter since, except receiving a polite note of acknowledgments. I'll trouble you my princess of fair lilies of all the valleys in the world, to hand me a cup of tea, and don't let your zephyr foot touch my gouty toe."

"I fear," said Mrs. Maxwell, with a quaint smile, "I must be so rude as to call you to order Colonel Arnott, on account of the expressions you address to my daughter—you will make her quite vain and silly."

"No fear of that mamma," whispered Griselda.

"Why, my dear madam," said the Colonel, "there is decidedly some truth in what you say. I beg pardon, it is all truth, every word of it. It was just the way I was myself spoiled. I had a fond mother, ma'am and she used to call me her little pigeon, just as if there is, or ever was, any resemblance between me and a pigeon; but however peaceful the nickname, it led once to a very serious combat. The occasion was this. When Lord Clive was leaving Calcutta for the last time, in the year 1767, there was a great crowd of ladies and gentlemen—officers, civilians, nabobs and lascars assembled on the river's banks to see him depart, and nothing would please me but to stand in the foremost rank, gaping like a bull-frog for a thunderstorm, when somebody from behind knocked my cap over my eyes, and called out 'Well Pigeon, are you here?' I turned round, ma'am, and saw Samuel Blubbertub, son of Assistant-Commissary Blubbertub, who had been di-rated by Clive the week before for misappropriation of government stores. I looked hard at him, 'Yes' said I. 'Owl, I'm here—as good right as you or your father either."

'Take that for your impudence,' said he, giving me a slap on the cheek.

'Tit for tat,' said I, giving him a thrust in the stomach that sent him yards away, when back he came in a rage, and in I went in a fury, and we grappled my boys like two tiger's whelps, when more by good luck than good science I fortunately pushed him into the river just as he was preparing for a heavy thrust. At that moment who should come up but Clive himself.

'What's all this?' said he to an officer, 'Who is this youngster?'

'That's young Arnott, my Lord, son of Major Arnott; his mother calls him the little pigeon.'

'Does she, by Jupiter?' said his lordship, 'the simple woman; he looks a deuce sight more like a hawk. Who is that other fellow?'

'That's the son of late Commissary Blubbertub; he struck the first blow.'

'Serve him right, serve him right; I hate bullies. Well done, Pigeon,' said the hero of Plassey, as he stepped into his barge, and all the people laughed consumedly.

"Your adversary was not drowned I hope," said Mrs. Maxwell, who had listened attentively.

"No ma'am, he was pulled out by a half-drunken lascar, who gave him a good ducking during the operation."

Tea having been dispatched, the company adjourned to the drawing-room, where Miss Arnott again sat down to the pianoforte and played her last new piece with great brilliancy of execution, the old Colonel's tongue rattling away all the time, telling wonderful adventures to Maxwell and the boys; while Mrs. Arnott, drawing out her little work-table, sat down within chatting distance of Mrs. Maxwell, who, with Griselda, earnestly begged to be employed. This, however, Mrs. Arnott would only allow to a limited extent. Henry sat half-hidden in a corner, and seemed to take great interest in the movements of Griselda's fingers; but our fair heroine was quite unconscious of this remarkable circumstance. When the piece was finished, Mrs. Arnott requested her son and daughter to sing a duet, which they did. This being over, and the performers duly thanked, Mrs Arnott asked Griselda if she ever sang, and that young lady timidly replied, "I try sometimes."

"Then you must allow me the pleasure of hearing you, my dear," said Mrs. Arnott.

"You may sing that ballad you have lately learned," said Mrs. Maxwell, "it is a patriotic ditty, called 'THE FORSAKEN WIFE'."

"I cannot sing very well," said Griselda.

"Try, my dear," said Mrs. Arnott.

"Do, Griselda," said Isabel.

"Miss Maxwell will not refuse us such a great pleasure," said Henry.

Thus urged, Griselda sat down to the piano—for she had made some progress in music—and sang with touching earnestness the following simple ballad—

May I not weep for days gone by,

Or speak of home, once gay and fair;

Must I not breathe one tender sigh,