a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Sundown Stories

Author: Dorothy Drewett

eBook No.: 2100141h.html

Language: English

Date first posted: 2021

Most recent update: 2021

This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore

by Dorothy Drewett

Illustrated By Ethel Wood

C O NTENTS

The Home of the Nursery Rhymes

More about Mary’s Little Lamb

More about Simple Simon

The Stolen Tarts

Contrary Mary’s Garden

The Girl who did not Like Sewing

The Edge of the World

’Tis at Sundown that the Fairies come

Breaking their fetters from the West.

In a Dreamship when the Day is done

They come to live in my Hours of Rest.

They tell me stories of Nursery Days,

Of the Things Unseen, yet always near.

Of the Spirits of Flowers, and Insects ways

Of the Joy of Life, and the Myth of Fear.

“AND where do all these Nursery Rhymes live, mother?” inquired a dear little boy one night, after he had listened to the nightly recital of all his favorites. His mother, who had been repeating the old old stories of “Little Jack Horner,” “Little Miss Muffet,” “Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary,” and “Queen of Hearts,” besides many others, to him, now seemed puzzled at his question.

“Where do they live, dear?” she repeated half wonderingly; “indeed, my little boy, I—I—cannot tell you.”

“Who will tell me then, mother?” he persisted.

His mother seemed completely bewildered. “You will have to ask a fairy, my love. There, there, now, it’s time the candle was out. Kiss me goodnight—and go to sleep, like a good boy.”

Little Charlie was really a very good little boy, and obeyed his mother. He, therefore, stopped questioning her, and allowed her to tuck him up and put the candle out.

After listening to her footsteps on the stairs, for a few moments, he sat upright in bed, when they had died away, and all was silent. “I would like to know where they live—I really would, indeed!” he murmured; and, as he did so, he raised his eyes to the window, which had been left open. Just one star seemed to shine in the sky, and as he continued to gaze at it, it seemed to grow bigger. It did grow bigger—until at last he knew it was coming nearer—and he watched it, delighted, as it floated downwards to him. He watched it so earnestly that his eyes grew tired, and for just one moment, he closed them.

When he opened his eyes again, he found a beautiful silver fairy climbing in at the window. She was arrayed in a gown of shimmering silver gauze, her crown and her dear little shoes, gloves and wand, all being of silver. A dainty cloak was flung over her arm, and this Charlie could see, was also of silver, with a blue lining, like the sky on a summer’s day.

“I heard your question,” she said in a voice like a silver bell, clear and sweet and low. “And your mother was quite right when she told you that only a Fairy could tell you where the Home of the Nursery Rhymes is! I am a sky fairy—one of those who see everything and hear every word that is spoken. That star,”—and here she pointed upward—“is my home. All sky fairies live in a star.” Charlie was amazed to find that the star he thought was floating down to him, was still shining in the sky.

“Just when you looked up and watched me coming to you, a cloud came before my star, and, consequently, still seeing something bright, you mistook me for the star itself. I have left my home for awhile to show you the Home of the Nursery Rhymes to-night.”

Charlie needed no second bidding, and was scrambling out of bed, when he suddenly remembered that he was still in his pyjamas.

“Could I go like this?” he asked timidly.

“No—no indeed! Besides you’re ever so much too big for my chariot,” she laughed, and her laugh filled the room like the sound of silver chimes.

“Hush!” he said warningly. “My mother will hear.”

“My presence is invisible,” said the fairy, “my voice inaudible to human ears, except yours, and for the moment you are enchanted. Look again at your apparel, and you will see now that it is quite fit to accompany me.” Charlie glanced nervously down, and was half afraid when he saw upon his feet, silver shoes like the fairy’s. He next discovered that his pyjama suit was gone, and he was arrayed in silver, with a little silver cloak lined with blue to match the fairy’s.

There was a silver crown on his head, set in the centre with a tiny star, and in his hand he held a wand of silver, upon the end of which was another tiny star—even as he was tiny.

“Come quickly!” said the fairy. “We have not much time. We have a million and one miles to travel to the Nursery Rhymes’ home—to say nothing of coming back. The way is always longer when you are coming home from the scene of pleasure.” All this while, she had been making her way to the window, Charlie following as quickly as he could.

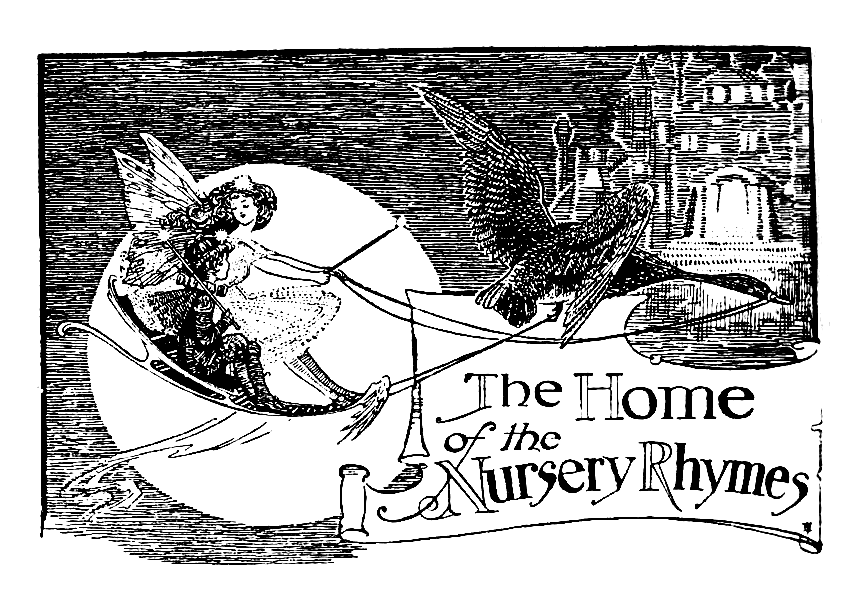

“Jump into my chariot!” and Charlie followed her into a beautiful little silver chariot which was waiting by the window-sill. It was drawn by a lovely bird, whose wings were lined with soft blue down. The fairy took the silver rein and said, “Ready!” at which they began to soar upward—bird, chariot, Fairy and Charlie, all together. In an instant the World was left behind, and they were among the stars, above the clouds, spinning along in the cool air, as easily as if Charlie were in his Daddy’s motor-car. But this chariot went at a speed that beat every motor-car out of record. “It is wonderful,” he said with delight, “and I don’t feel a bit sleepy!”

“Sleepy!” cried the fairy. “Of course not! You are enchanted for to-night, and sleepiness is quite out of the question. Are you afraid?”

“No; neither sleepy nor afraid; and that I think is very wonderful,” he answered.

“If you were another little boy than Charlie, you would be afraid, but being Charlie, and enchanted, you could not possibly be, if you tried. Another little boy I know, who wanted to visit the Moon, which is quite as far away as the Nursery Rhymes’ house, came up with me in my chariot, but got about as far as this and felt afraid. The minute he felt afraid he tumbled straight out of the chariot—head first—into—”

“Oh, dear!” cried Charlie in alarm; “was he hurt? Suppose he fell into the sea. Where—where did he fall to?”

“If you had waited till I finished my tale you would know now that he fell straight out of the chariot, head first into bed—and didn’t remember a thing that had happened when he woke in the morning.” The Fairy stopped speaking a moment to hand the reins to Charlie, who took them, just as easily as if he were used to this sort of work, or pleasure, or what you will.

“Yes! This boy fell into his own bed, and when he awoke in the morning he had forgotten everything that had occurred. Now, you won’t forget, because in a few moments you will pass the gates of Memory, and will never forget till the end of your life—even if you live to a hundred years—anything that ever happened to you or anything that was ever said to you.” She pointed suddenly with her wand, then snatching the reins out of his hand, she cried—

“We are passing through the gates of Memory”— and they both remained silent as some big, grey gates came into view. In a moment they had passed through, and, as Charlie turned to look round, he saw that the gates were a beautiful rose color. He asked the Fairy why they had thus changed, and she answered—

“There are two sides to the gates of Memory—the sad and the joyful. The grey side is for the sad side, the rose color for the happy. Which side did you see most of as you passed through them?” replied the Fairy.

“I think I saw most of the rose color, for I was so wonderstruck at the change of color that I looked long at it.”

“Then your life will have more happy moments than sad ones in it. Congratulate yourself, my child.”

For a long while they sped along silently, and to enliven the journey, the bird sang a song as it went— such a wonderful song, that Charlie was enraptured, the tones being ten thousand times sweeter than Charlie’s pet canary.

A great golden palace suddenly loomed out of a soft blue haze, and from its hundreds of windows gleamed streams of light.

“They are revelling to-night. Times are changed —they are past the sufferings they went through on earth, and are happy now,” cried the Fairy. “This is the Nursery Rhymes’ Home!”

Before Charlie could utter a word, the bird had silently fluttered before the palace portals, and they had alighted, Charlie remembering to offer the Fairy his arm.

The palace hung in the air, which was blue like the sky, and Charlie and the Fairy took three steps into the air before they reached the door. As soon as they stepped inside they were greeted by a merry voice, saying:—

“Old King Cole was a merry old soul

And all within his halls are welcome!”

And a portly old gentleman dressed in scarlet, with his crown awry, came forward, followed by three fiddlers, who immediately struck up a tune when the king was speaking; and two other quaint characters, one carrying a bowl and the other a pipe.

The Fairy, however, took no notice of Old King Cole, but walked along the hall into another room.

It was like a scene from the pantomime inside this room. Tiny green hillocks were arranged around, and the snowiest of snowy sheep grazed upon them. One could almost imagine one was out in the country to see the green grass, and the little daisies peeping up here and there. A sweet little voice greeted the Fairy and as they entered.

“Little Bo-Peep she lost her sheep,

And couldn’t tell where to find them;

Let them alone, and they’ll came home,

Bringing their tails behind them.”

“And they did come home,” said the prettiest little shepherdess in the world, in a frock of pink and blue, “and never, never did they get lost any more.”

The Fairy and Charlie passed out of this room into another, which was arranged like a kitchen. At a table stood a queen, whom Charlie immediately recognised as the “Queen of Hearts,” by the song she sang as soon as she saw them—

“The Queen of Hearts,

She made some tarts.

All on a summer’s day.

The Knave of Hearts

Stole those tarts,

And took them clean away.”

“But you are not going to have them this time, my lad,” cried the Queen angrily, as she saw Charlie, and stamped her foot. “Away this instant!”

Of course, they left the room instantly, the Fairy explaining that since the Queen’s experience, when she lived on earth, she suspected every man and boy of being a thief.

Yet another apartment did they visit—and this time it was the garden of “Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary.” In the centre stood a very quaint little maiden, holding a watering-can in her hand, and when she saw the visitors, she, like the others, burst into song—

“ ‘Mary, Mary, quite contrary.

How does your garden grow?’

‘Silver bells and cockle shells,

And pretty maids all in a row.’ ”

Here she pointed with one dainty hand at the garden patch before them. There rose on the air the chime of tiny bells, and Charlie saw upon several plants some silver bells waving to and fro. The beds of flowers, which each had the face of a pretty maid laughing from its centre, were bordered with cockle shells.

“They would be wedding bells if I could find a man for each of my maids!” sighed Mary, as she lifted the watering-can.

The next room they passed into was very luxuriously furnished, and in the centre was a table, beautifully set for dinner, at the head of which sat a jolly old king, smiling in anticipation at a huge pie which had been placed before him. As soon as he spied the visitors, he began to sing the well-known tune—

“Sing a song of sixpence,

A pocket full of rye,

Four and twenty black birds

Baked in a pie.

When the pie was opened, the birds began to sing;

Was not that a dainty dish to set before the King?”

“Will you not have some?” he asked. “Don’t be afraid. We do not live on earth now, and there will not be live birds in this one. Oh, no, nothing so shocking! Only earth people could devise such a cruel joke. Can you imagine anything more terrible than your dinner flying out of the window, and picking off the nose of your maid? Such a pretty nose it was, too!— and the loss of it quite spoilt the maid. Dear, dear, dear me,— ha, ha, ha!”

They accepted the king’s invitation to have some of the pie, and Charlie was very surprised to find that the Fairy’s piece of pie was the color of gooseberries, while his own was strawberry color. He asked the reason why, and was informed that his piece of pie represented “health,” the Fairy’s slice “happiness,” and the king’s own, which was raspberry color, “mirth,” the best thing in the world, so he told them, and that there would be a great deal less sorrow and disease on the earth if people took a little more “mirth.”

As soon as they had finished, which was after the king had had three slices to Charlie’s one, a loud bell rang, and the Fairy arose in great haste, crying—

“There is hardly time to see Jack Horner, Little Miss Muffet, Boy Blue, or the Lady who rode to Banbury Cross.”

But somehow they made time, and paid a flying visit to Little Miss Muffet, who, still very fond of curds and whey, was supping some out of a basin. There were no big spiders to frighten her here, as there had been on the earth, so she supped her curds in peace. Little Jack Horner was discovered with a pie on his knees, and just as the Fairy with Charlie entered, he “put in his thumb, and pulled out a plum,” and said, “What a good boy am I.”

“Indeed you are!” said the Fairy laughing— and then they visited little Boy Blue, whom they found with little Tom Tucker, who was amusing Old Mother Hubbard by singing for his supper. When the song was ended, Mother Hubbard’s wonderful dog laughed heartily, and shouted “Bravo!” at which the kind old dame went to her cupboard. Instead of being empty, as it was when she lived on the earth, it was filled with goodies of all kinds.

The “Lady who rode to Bambury Cross” proved very interesting. Charlie admired her beautiful white horse, and was charmed with the music which issued from the rings on her fingers and the bells on her toes.

As they were preparing to leave, a great noise of laughing arose, and Charlie looked pleadingly at the Fairy.

“Yes; we must see the Old Woman who lived in a Shoe,” and they passed into an immense hall. But the shoe was entirely different from the one that the thousand and one children had occupied when they were on the earth. It was of solid gold, and each of the children was arrayed in finest silver clothes, and, instead of the whipping they used to get, the old woman was giving them strawberries and cream upon golden plates, and she was joining them in their laughter.

At the door of the Palace, they met the Four and Twenty Sailors who ran away from the snail. They saluted the Fairy and Charlie, who were just getting into the silver chariot, drawn by the Bird.

The last sound that reached their ears as they floated away from the Home of the Nursery Rhymes was the song—

“Three blind mice, three blind mice—

See how they run, see how they run.”

“That,” said the Fairy, “is the farmer’s wife, who cut off the tails of the three blind mice with her carving knife. In her new home here, she has no use for the knife. But if you go to see her, she proudly tells you the whole story, just as if it were not known in every corner of the globe by every child. She will never forget the brave deed she wrought when she dwelt upon the earth.”

“Oh, please tell me whatever is that queer object balancing itself upon the wall?” cried Charlie.

“Don’t you recognise Humpty Dumpty?” and, in spite of herself, the Fairy had to laugh at Charlie’s look of amazement, and his exclamation, “But he is mended! However did that happen?”

“Oh! in this wonderful land where everything and everybody is happy, they found a cure, and poor, unfortunate Humpty Dumpty became whole again.”

For awhile Charlie was silent.

“How happy they are!” he said at last. “Their troubles are all ended!”

“Yes; and it just shows you that everything, even the worst catastrophe (like Humpty Dumpty’s) comes out right in the end. Earth people are so foolish that way. If they would only firmly believe that even the worst trouble ends well, how much less sorrow (mostly imaginary) would be saved.”

“Dear, dear! there is an immense giant upon the earth, and he grows bigger every day. His name is ‘Worry’— beware of him!”

The journey home was a very long, but delightful one, the bird singing all the way. The sun was just beginning to peep over the hill when Charlie tumbled into bed, thanking the Fairy for her kindness.

When he awoke, his mother was bending over him, looking rather anxious.

“This comes of telling you Nursery Rhymes just before bed-time. You have just been saying ‘Humpty Dumpty sat on the wall,” she said.

Then Charlie sat up and told her all his adventures of the night before, hoping she was not angry that he went so many miles without her permission. She was not one bit angry. She only smiled, and then hugged him closer to her.

* * * * * * * * *

Charlie is a man now. He is a rich man, and a prominent one in his native city. He can faithfully say that most of his memories are happy ones—that he can remember everything that has happened to him in his life, especially the good and pleasant things. Also, he is a firm believer in what the Fairy told him about the most hopeless catastrophe coming right in the end—and last, but not least, he enjoys perfect health. This he attributes to the slice of pie he ate at the King’s table in the Home of the Nursery Rhymes.

“Mary had a little Lamb,

Its fleece was white as snow,

And everywhere that Mary went

The Lamb was sure to go.

It followed her to school one day—

YOU know the rest, don’t you children? of how Mary’s little lamb went to school and was turned out by the teacher; how the stove was upset and the school caught fire, and all the children had to be rescued; how the Lamb was left inside, and was saved by a kind fireman— Oh! yes, you must surely know, for Mother Goose told the tale. But an old friend of that famous Lamb met me the other day, and told me many interesting stories of the Lamb’s adventures on earth that have not been printed in a book yet.

After all the excitement over the fire had died down and it took a few weeks for Mary and the Lamb to recover their fright, they ventured out for a walk in the meadows. Mary’s hair was newly curled and beautifully tidy. She wore a shady hat, and a clean white frock sprigged over with little blue flowers. The Lamb had just been washed, and his woolly coat was indeed “white as snow,” as the poetry-book says. The sun shone peacefully, and the little daisies nodded in the green grass. No one could ever, ever, have guessed that any adventures were pending. When they had selected the greenest spot in the meadow (and it was very hard to do that) to sit down, Mary opened her little lesson book and began to learn her spelling. She was as good as the Lambkin was white—oh! indeed, she was a good, good, goodie little girl.

The Lamb stretched out at full length, and closed his eyes.

“Don’t be lazy,” said Mary. “Couldn’t you learn how to spell?”

The Lamb yawned, and shook his head.

“I am far too young,” he said.

“You have told me that before. Someday you won’t be a lamb—you will be a sheep.”

“I shall never be that. If I lived to one hundred years, I should always be a Lamb.”

“We must both grow up some day,” sighed Mary.

Just then a great black shadow hovered over them, and at first the Lamb thought it was a cloud, but it wasn’t. It possessed a voice that croaked out, “Come with me,” and a claw was thrust into the thick soft woolly part of the Lamb’s neck. The Lamb felt himself leaving the earth; not actually dying, you know, but rising into the air; drawn upwards by the cruel claw stuck in the back of his neck. It is to be sadly feared that the Lamb did not bear his fate like a man. He couldn’t be expected to; so he kicked and bleated all he could. But he kept on rising in the air. Can you guess what had happened to him? No! he wasn’t in an aeroplane, for these were not invented in the Lamb’s day. He was in the clutch of an eagle. Of course, he knew he was going to be eaten up. The Lamb had heard of this happening to other lambs, but had never imagined it would happen to himself, for he had always thought that what could befall an ordinary lamb would never, never, never happen to him.

Now he knew all the conceit of the past had been for nothing. He had imagined himself a special sort of a lamb that could never grow old and never die. He might just as well have been sold to the butcher.

In fact, now that this had happened, he would much rather have been sold to the butcher. Tears dropped out of his eyes, right down on Mary’s clean dress, and the loudest bleats that ever proceeded from a lamb’s throat came from this one.

The Eagle’s home hove in sight at last. Right on top of a high cliff it had gathered a few sticks together, and made its nest. So high up were they now, that the Lamb, in looking down, could not distinguish Mary from the daisies in the meadow. He hoped she had disappeared from the meadows, and run for help.

“I hope I have given you a big fright!” said the Eagle. “You notice you are still alive.”

“Yes, I am still alive,” answered the Lamb; “but how can I get home?”

“Oh! very easily— very easily indeed,” answered the Eagle. “There is only one home for you now.”

“Indeed— indeed?” asked the Lamb eagerly. “Where?”

The Eagle opened its large beak. “Down here!” it said.

The Lamb shuddered. “When — when — will the first bit of me go home then?” he asked, trying to be sarcastic.

“Oh! very soon. I’m not hungry just this minute. You are going to be my supper. Lamb in the moonlight is lovely.”

The Lamb made a mental note, “There is time to get saved,” he said. He was quite sure he was going to be saved.

The Eagle flew away for awhile. It knew its supper couldn’t run away.

The Lamb peeped over the edge of the cliff. It was a precipice, and if he jumped over he would only fall into the sea, and be “drowned-dead.” So he decided to wait in patience. He had not to wait long before a great Seagull flew by. The Lamb hailed the beautiful bird, and after some persuasion, and many assurances that the Eagle was away, he extracted a promise of help. The Seagull flew away for a few minutes, and returned with a pair of large wings, which it fixed upon the Lamb’s back.

Joy! the Lamb flapped them, and spread them, and rose in the air.

“Thank you, thank you!” he said to the Seagull. “How can I manage to repay you?”

“Just by a simple thought,” and the Seagull paused before adding, “Try to be less conceited.”

For a moment the Lamb felt as if he didn’t like the Seagull any more, then he remembered the wings, and promised to try.

“How shall I return the wings?”

“Oh, don’t let that trouble you. They will melt as soon as you get to the earth. Only if you lived up high in the air would they stay.”

So Mary’s little Lamb flew with his borrowed wings down to earth. His mistress was eagerly awaiting him, with arms stretched out to receive him.

“Lambkin,” she said, “I thought you had gone for ever.”

“I am not to be lost so easily,” he replied.

“I got such a scolding from Mother,” said Mary.

“What for? Because you had lost me?” he asked eagerly.

“Because I had some spots on my clean dress.”

The Lamb was decidedly taken aback, but he remembered the Seagull’s words, and said nothing. Besides he did not want to confess that the spots on Mary’s dress were his tears.

“I have made a resolution,” said the Lamb.

“What is it?”

“That I am not going to learn spelling.”

“Yes, you told me that before,” said Mary.

“The reason is different!”

“What is it?” asked Mary.

The Lamb hesitated, then whispered :

“Because I am an ordinary Lamb after all—liable to be eaten by eagles or killed by the butcher any minute. No lambs I ever heard of could spell, and they all grew up into sheep. That’s what I’m going to do, if I can.

But he couldn’t, because nobody has ever heard of Mary’s little Lamb growing up, though there was a decided improvement in his character from that day.

HOW Simple Simon met a pieman going to the fair, and asked him to show his ware; and how the pieman asked Simon to show him first the penny, also Simon’s answer, “Indeed, I have not any,” have become history to children. There is also a well-known tale of Simon’s ambition “to catch a whale, but all the water he had got was in his mother’s pail.” Most children know of how Simon was sent to get some water, and how he tried to bring it in a sieve. In fact the silly things that Simon did are without end. But the following story is of a day in Simple Simon’s life which has not yet found its way into the story-books. One day Simon made a resolution that he would waste no time at all on that day — and he also threw in a rather faint resolution that he would try not to do anything silly, though he felt doubtful about keeping it. He dressed himself with care — that is, upon looking at his clothes which he had worn the day before, and finding the right side rather soiled, he decided to wear them on the other side. The “inside out” side was perfectly clean, so why not? reasoned Simon. The only thing that worried him was that he could not turn his boots inside out too. He felt it was such a waste of time scraping the mud off them, and he was so anxious to get out into the sunshine. He had awakened extra early, and his dear mother (who was never cross with him, no matter how silly he was), was not yet stirring, so Simon thought he would give her a surprise and get breakfast ready. Now Simon and his mother always had an egg each for their breakfast.

“To save time!” said Simon, “I’ll pick out the smallest eggs in the basket. They won’t take so long to cook — and also it will save time not to boil the water. I’ll just put them under the tap. That will do as well.” When he had done this, he said,

“To save time, I’ll start and have my breakfast. Perhaps I had better eat Mother’s breakfast, too, as she is not awake yet. It will save time.”

So he sat down, and imagine his dismay when on taking the top off his egg he found that it was quite raw.

“I wonder!” he said, “if Mother’s egg is the same?” and was very much surprised to find when he took its top off, that it also was quite raw.

“That is very funny,” said Simple Simon. “But I won’t waste any more time about breakfast,” and he went out into the garden. The flowers were all nodding gaily, and invited Simon to enjoy their perfume. He looked longingly at them, but said, “No! I must not waste a minute to-day. I must not stop to smell the roses and violets. I must do something useful.” He wandered round and round the garden in search of something to do. No! all the beds were trim, all the trees pruned, everything smelling sweetly, everything in order, for Mr. Gardener-man had been there, and fixed up the garden. Simon came to the gate.

“I think it will save time if I climb over it, instead of open and shut it.”

So he climbed over it — but he landed on his crown on the other side.

“Ma-a-!” he heard someone say. The voice seemed neither to come from the trees nor the ground nor the right nor the left.

“I am behind you,” said the voice, noting his dismay. “Turn round.”

“It would be waste of time,” said Simon simply, and did not mean to say anything wise.

“Oh, well, I shall have to come in front of you. Have you seen a tan and black goat lately, named Tango?”

Simple Simon scratched his head. “Can you wait till I get a looking-glass,” he said.

“Why!”

“Because you look very much like a black and tap goat.”

“Do I? You don’t mean to say I’ve lost myself,” said the owner of the voice, and straightway raised a wail, “Ma-a-a.”

“No—but perhaps you have lost your way,” suggested Simon. “Do let me help you.”

He felt quite grown-up and wise, for here, at last, he had met something simpler than himself. “So your name is Tango?” he said. “Why did they call you that?”

“First because the tan of my coat is the ‘tan-go’ shade, and secondly because of the graceful steps I take,” answered the Goat, then as the memory of her lost self rose before her she uttered another wail, “Ma-a-.”

“This is really dreadful,” said Simon, with tears in his eyes. “Where do you live?”

“Murrumburrumbah—ma-a-a.”

“Dear, dear, dear,” said Simon, racking his brains. “That’s a long way from here. We’ll have to get a motor-car. Here’s one coming now.”

A beautiful motor-car, with velvet cushions, came in sight. Its only passenger was a rocking-horse. It was driven by a wise-looking boy about Simple Simon’s size.

“Where are you going?” said Simon.

“Murrumburrumbah,” said the Rocking-horse.”

“Can we get in?” asked Simon. “We are going there.”

The Rocking-horse replied. “Well, yes! I suppose you can. You’ll be the first goat that has ever ridden in a motor-car.”

“I’ll set the fashion,” said Tango. “Already the colour of my coat is the ‘rage,’ and everybody is imitating my steps. Now all the goats in the country will take to riding in motor-cars.”

Simon was lost in rapture, at the graceful way the Goat leapt into the motor-car. When he was safely wedged between Tango and the Rocking-horse, away they went—over hill and down dale, as fast as they liked. Policemen shouted, people stopped to look, but they cared nothing, and on they went.

At last they arrived at Murrumburrumbah, and a little girl and little boy came running out to meet them. The Rocking-horse belonged to the little boy, but Tango was the little girl’s very own. She cried with joy when she saw her dear goat, and thanked Simon very much for taking care of her.

It took a very long time to go back again to Simon’s home, for the motor-car, also belonged to the little girl’s mother, so Simon had to walk back. As he trudged along he kept wondering if he had saved much time that day after all. When he got home it was quite dark and Simon was very hungry. When he told his mother about his adventure, and asked her if she thought he had saved much time, or been very useful, she pointed to the raw eggs, and said, “Never mind about saving time by doing things quickly. Do them well. You know someone said, ‘There is a best way of doing everything, even to boiling an egg?”

“Mother!” said Simon, solemnly, “I think I am getting wise.”

His mother looked frightened. “I think I’d rather have you as you are. You are useful to make people laugh—and that is a big thing,” she said, and made Simon happy again.

The Queen of Hearts she made some tarts,

All on a summer’s day;

The Knave of Hearts he stole the tarts

And took them clean away.”

THE Knave really could not help taking the tarts — they looked so nice — but he should not have done so, should he? You see, the Queen had left them in such an easy place — to cool — on a pantry shelf with the window open — that the Knave going past had only to put his hand in, and in a second he had hold of the whole plate full. This does not, of course, mean to excuse him. He simply should have “resisted temptation,” as the grown-up story books say, but only a hungry boy or girl like you or me knows just how hard that would be. It was near dinner time, and a longish while from breakfast time, and the Knave was a hungry boy, and the tarts smelt good and were easy to get. So that is how it happened. The poetry books don’t tell you exactly everything that happened after — but I happen to know — and I’m going to tell you.

When the Queen missed the tarts, she, of course, asked the Pantry Maid, who, of course, asked the Scullery Maid, who asked the Maid of the Broom, who had not been anywhere near, but referred her to the Page who blew the Bellows, who was so taken aback at the question, that he dropped the Bellows and took to his heels and fled.

“You were right!” said the Scullery Maid to the Maid of the Broom. “The Page of the Bellows took them—but he has fled—so what shall we do?”

“Go after him!” said the Maid of the Broom, and straightway they ran out into the garden—so that when the Queen came back she found only the Pantry Maid in tears.

“They are evidently all guilty,” said the Queen. “Call the Knave of Hearts in to dinner—and stop crying.”

So the Pantry Maid ran out into the garden too — and strange to say she did not return — neither did the Knave of Hearts come in to dinner, which meant that the King and Queen had dinner alone.

Now, when the Page of the Bellows had fled in fright at the Scullery Maid’s question, he ran through the garden in the hope that he would get past the sentries at the gate, and then into the high road, where he would be safe. For he knew that such was the nature of the King and Queen of Hearts that it would be no use to deny having taken the tarts. To say, “no he had not been near,” would immediately convict him. Thus he made up his mind to run as hard as he could before Trouble could overtake him. Well, as he was running, who should he meet but the son of the King and Queen of Hearts—the Knave himself — eating as hard as he could at the very tarts that had caused the trouble.

“Have one?” asked the Knave generously. “You like strawberry tarts best, don’t you?”

The Page of the Bellows was between two fires— because he dared not refuse the Knave’s offer, and yet if he ate a tart, he would be just as good as an accomplice. However, he thought as he was running away for good, and probably would not have anything to eat for a long while, he might just as well taste a tart. He had no sooner taken his first bite when he heard two voices.

“There he is! there he is! actually eating a tart”— and there before him stood the Maid of the Broom and the Scullery Maid. But before he could say a word, the Knave offered them a tart each, and as they could not refuse, they took them silently, and began to eat.

Just as they were finishing, the Pantry Maid came upon them, saying, “You are all guilty—you are all guilty”— but when she saw the Knave eating too. she was silent. For she knew she must never tell that the Knave was the guiltiest of all. Besides, the Knave was offering her a tart, and she dared not refuse the royal favour.

Now, these tarts were dangerous to eat. They contained magic. Only the Queen who had made them knew this. She had poured a few drops of delicious magic-flavouring into them, that had been given to her by a genii, or “magic man”— and it was intended only to be tasted by Kings and Queens. That is why the Queen was so angry when she found they had gone.

During dinner time, she told the King about her misfortune.

“Now, don’t cry about it,” he said; “it will be all right. The guilty ones cannot escape”—for he knew the tarts would leave a sign, and no one who had eaten would escape.

Down in the garden, the Knave, the Page of the Bellows, the Maid of the Broom, the Scullery Maid and the Pantry Maid were deciding what they had better do.

“Just go quietly back,” advised the Knave, “and I’ll make a clean breast of it. I’ll save you all.”

They all went back trusting the Knave, and when the Queen of Hearts saw them she exclaimed, “You are all guilty.” But the Knave pulled her aside and whispered something in her ear, to which she answered, “Oh! I wish it were true, but I can’t believe it — I really can’t.”

He had told her that he had eaten all the tarts — true to his word. But he could not make out why his mother should behave so strangely. He had indeed expected some dire punishment to fall upon him, and instead, here she was persisting that he had not eaten all the tarts, and hoping that he had. When they were alone he wheedled the truth from her, and learnt an astounding fact, that all who tasted that magic flavour would wear a king’s or queen’s crown forever. The Queen, thinking to make her own, and the King of Hearts’ crowns more secure, had used the flavouring, but it was just as joyous news to her to know that her son’s crown was also secure.

But we can’t finish up the tale till you learn what happened to the Scullery Maid and Pantry Maid, the Maid of the Broom, and the Page of the Bellows.

The next morning, on coming into the kitchen, each discovered that the others wore a gold crown on their heads, and in fear they guessed that it was the effect of eating tarts that were not intended for them. Just as they were deciding what to do about it (for the crowns were fixed on so that they would never come off), the Queen and the Knave of Hearts walked in. The Queen was all for turning them out at once, but the Knave pleaded, saying he had led them into temptation, and to let them stay. This proves that even Knaves are not as bad as their name.

“Well,” said the Queen, “they can stay, but their punishment will be just as great as if they went. They should not have sought to hide at the back of you even though you tempted them greatly. Wrong-doing can never be hidden as you see.”

The Queen’s words proved to be correct, for what greater punishment could be thought of than for a Page wearing a crown, to be forced to go on blowing bellows, and becoming the ridicule of the whole household. Likewise, the Scullery Maid, the Pantry Maid, and the Maid of the Broom.

‘Mary, Mary, quite contrary,

How does your garden grow?’

‘With silver bells And cockle shells,

And pretty maids all in a row.’”

IT really did, too, you know. Though you might not believe the story-books, though you may laugh at Nursery Rhymes, I really can assure you that Mary spoke the truth when she said “that silver bells and cockle shells and pretty maids all in a row,” grew in her garden.

It was a lovely garden, but Mary of course was very contrary about it. The row of maidens each had a name. First came Lily, fair and tall, in a white dress and a golden crown. Next came Violet, a tiny wee maid that hid herself under the green leaves so modestly, and let nobody see her exquisite blue dress. Then there came Daisy, the very gayest maiden of all, with a frilly white dress, and lovely eyes. Everybody declared Rose to be the loveliest of the maidens, but I’m afraid she was rather vain. Sometimes she would be seen in a white dress, sometimes in pink, at other times in red, and also in yellow. But if a sweet perfume was any proof of virtue, then she must have been the best. May was another sweet flower-maiden in the row, but when Poppy stood beside her, she looked whiter than ever, for this was such a bright maid. Most dignified of all was Marguerite. Now this is where Mary was so contrary about her garden. She let all the flower-maidens grow in a straight row, where it would have been much better for the appearance of the garden if she had arranged them in groups. Lily and Violet could not talk to each other because one was so tall and the other so small, and when Violet spoke Lily could never hear. Marguerite was parted from her sister Daisy, yet perhaps she would have liked much better to stand beside Lily, than have to listen to Poppy’s “scatter-petal” chatter all day long. Violet and Daisy were fit mates for each other—yet poor Daisy was squeezed in between May and Rose, and was quite overshadowed. And Contrary Mary thought her arrangement was best, yet all the maidens were pining for their own favorite companion, and through Mary’s orders could not move to get nearer to them. Then the Cockle-shells were always a mistake in that garden. They really looked very nice, but they were unhappy because out of their element. They belonged to the sea, and should have been left on the seashore. But the Silver-bells, wherever put, are always in the right place, and with every breeze that blew they chanted a lovely song to delight the inmates of Mary’s garden.

Many people had told Mary of the mistakes in her garden, but she took no notice. Mr. Sunlight once told her that the Daisy should be moved from the Rose, where she could get more rain. Mr. Rain had told her that little Violet would get drowned from the drops which splashed down from the Lily on to its face. But Mary was contrary.

But one day a stranger came to Mary’s garden, and admired the Bells. “The music they make brings one to think of cool fountains on a hot day; and on a freezing day makes one dream of sunny patches. Yet they do not make one discontented. Rather do they make one cheerful. You were wise to plant such silver ringing bells in your garden. Mistress Mary.”

Then he walked round and admired the Lily.

“This is for purity,” he said, “and peace and all things calm. It shows good taste on your part, Mistress Mary, to plant such a beautiful flower in your garden.” Then his eyes fell on the Violet.

“Ah! Humility is the Violet’s virtue. You have done well again, Mistress Mary.”

He stood and looked down the whole row, murmuring the meaning of each flower-maiden.

“Daisy for gaiety, Poppy frivolity. May for pride, what a strange assortment in one garden? Let us see, purity, humility, gaiety, frivolity, cheerfulness, content, pride—and the Rose for love. Well Mistress Mary, since you have a Garden of Contraries, the whole is redeemed by the Rose.”

Mary laughed.

“You have forgotten the cockle-shells,” she said. “I brought them in to make a border.”

And then the stranger laughed.

“Mary,” he said, “the cockle-shells with their sharp points, are perhaps after all an appropriate border to such a Contrary Garden. One is apt to cut one’s hands on the shells when trying to pick a lily. Don’t you find it hard to weed your garden?”

“I am always weeding,” said Mary, “and have to water much.”

* * * * * * * * * *

Now let me whisper a secret. There was not any garden (such as we make with our hands) but the Garden spoken of was Mary’s Own Contrary Self. We all have a garden to cultivate, and must be very careful what we grow in it. Most of our gardens are Contrary Gardens. So many beautiful flowers, such as Purity, Cheerfulness, Humility and Sweet Content grow side by side with thistles, mushrooms, and stinging nettles. Did you ask, where is this garden of ours? Why, dears, in our heart. But as long as we weed often, water well with Sweetness, and keep the Rose of Love alive and blooming, our garden will be beautiful.

RIP, Rip!

“What was that?” asked Mother. “Oh! Maggie, your dress again.”

“I don’t care,” said Maggie.

“But I do!” said Mother. “Because I shall have to mend it. Your sewing is disgraceful. All girls of your age take a pride in their appearance. But I think you would go for ever with a torn frock and never think of—”

But Maggie was out of sight, and Mother, finding that the lecture was being wasted on bare walls, became silent.

At tea-time Maggie returned; but alas! with a wider “rip” in her dress.

“You will have to mend it yourself,” said Mother. “I’m simply tired of mending your torn stockings and dresses. Don’t they teach you sewing at school?”

Maggie did not answer.

The next morning Mother handed her a little note for the teacher just as she was setting out for school. “It’s about your sewing,” said Mother, putting Maggie’s nicely-packed lunch-case in her hand. “You know, dear, something really must be done about your sewing. Every girl should know how to sew.”

“Wish I was not a girl then! I hate—hate—hate sewing.” She kissed her mother hastily and sped down the garden path.

That afternoon was devoted to sewing, and it was a bad afternoon for Maggie. She indeed hated sewing. The needle got sticky, and her hands hot, and in a while her head started to ache. The stitches would never come small enough, and when after much struggling she managed to stitch up an inch or two of what she thought was an endless seam, the teacher would come along and make her unpick it. Somehow the cotton always got dirty and the stitches would come out black. Then it would get in a knot, or break, or do something equally annoying. But this afternoon Maggie had worse than the usual bad time. The teacher (owing to her mother’s note) kept a special eye on her. It had been Maggie’s custom to do a stitch or two, and then fall into a little dream about play-time or dinner-time, or any other time but sewing-time. But no chance of that to-day. She was brought right out of the class and made to sit beside Miss Leeton, who simply made her unpick every stitch that was not perfect, and use clean cotton, and hold her needle properly. Poor Maggie! She was glad when the hour for closing-time came, and she imagined the hour for release was near at hand, and the horrible sewing would be put right away for another week.

Not so! To her horror Miss Leeton cried:

“Maggie Brown, I see your sewing has been sadly neglected, and so I am going to give you a special hour all to yourself after school. When the others leave, you will kindly stay behind.”

Now Maggie was too proud to cry, but she felt like it—especially when all the girls filed out, and Miss Leeton took up her sewing and began to set a fresh seam. How Maggie loathed sewing! and she came very near to feeling bitter things against Miss Leeton, only that that lady was also the History teacher and made the lessons so interesting. Maggie was top in history.

Presently Miss Leeton was called away for a few moments on other business—at least she said it would be but a few moments, and that she would be back soon. The moment the door closed on her, down went Maggie’s hands in her lap, and she fell into one of her long day-dreams. She yawned widely, and had just settled more comfortably into her chair when she heard footsteps, and the door flew open. Of course Maggie had thought it was Miss Leeton, and had stopped yawning, but she soon saw it was not. An old, old woman now entered, and then—what a noise of children’s voices followed—crying voices, laughing voices, cross voices, and sad voices. The Old Woman led the way, while the crowd of children followed her singing:

“There was an Old Woman who lived in a shoe,

She had so many children, she didn’t know what to do.”

“No, indeed! and I don’t know what to do; and now the doctor has ordered me away for a holiday, because, what with mending their rags and tatters, I’ve nearly ruined my eyes, and want a rest,” said the Old Woman.

“I am very sorry for you,” said Maggie.

“You’ll be sorry for yourself more, when I tell you what my business is with you,” said the Old Woman. “You’ve been chosen to take care of them while I’m away—to mend for them, to cook for them, and put them to bed.”

“—O-oh! dear!!” gasped Maggie.

“To begin with, you had better put on my hat. It will help you with the sewing.”

The Old Woman took off her hat, and handed it to Maggie. It was an immense Thimble.

“Now, come along and I’ll show you where we live.”

Maggie only too glad to leave the school-room, followed.

They soon came to a large Shoe, as big as a house, with windows in the heel and toe, and at the ankles there were big doors. The children, who were a most unruly lot, rushed in before them, and scampered upstairs where they made a fearful noise. The Old Woman took Maggie into the Toe, and there pointed to a whole heap of —horrors!—stockings; and the holes!—poor Maggie was speechless.

“There are eighty pairs of stockings there,” said the Old Woman, “and you had better start on them immediately. When dinner-time comes—there’s a big ham-bone in the kitchen that will perhaps make some broth. And be sure you whip each child well before you put it to bed.”

“Tell me one thing before you go,” cried Maggie. “Just one thing. Why—why have I been chosen for this?”

“Because you hated sewing, and practical experience is the only way to learn. The good fairies have specially favoured you by giving you this position. Why, you will have to learn how to send the children to school properly clad, with no holes in their stockings or dresses. Now, I must say ‘Good-bye,’ if I am to catch my train.”

The next instant she was gone.

“Oh, dear—oh, dear!” was all poor Maggie could, say as she looked at the pile of stockings. The children were racing up and down the stairs, falling out of the windows, banging the doors, and either crying or laughing at the top of their voices, and Maggie’s head was aching. “Because I hated sewing—this has come upon me.” She took up a needle, and tried to thread it with black wool thread. Now, there is a science in threading wool through a needle—and Maggie, although she had had many opportunities to learn, had never bothered. Now she wished heartily that she had. So the time went on, and when tea-time arrived not a stocking was started and no broth made, and no children whipped.

“I do wish I had taken pains with my sewing,” sighed Maggie. “If I could only have another chance.”

“So you shall!” came a voice—the voice of Miss Leeton—and Maggie felt a heavy hand shaking her. “Here I have been away for ten minutes, and you have been asleep. I see you are too tired for sewing to-day— so we’ll postpone the lesson for another time.

“No, no!” cried Maggie. “Teach me now, and I’ll be so good.”

The fact is, she didn’t believe she had been asleep, and was afraid that the Old Woman would find her again and make her mind the children. And she sewed so diligently that she grew to like sewing very much, and actually she won the sewing prize.

But she had no more visits from the Old Woman who lived in a Shoe.

GUESS what I was told at school to-day,” said Horace to his dog Gip. “Such nonsense you never heard.”

Gip wagged his tail violently, as if eager to know, so Horace continued talking to him as they walked along.

“They told me that the world was as round as this orange. Did you ever hear such a tale?”

Gip went on wagging his tail more violently still, and also kept an anxious eye on the cake his master was rapidly devouring. It was disappearing so quickly that Gip was beginning to wonder how much would be left for his share.

“Yes, they teach nonsense at school;” said Horace. “Telling me the world is round, indeed.” He took another big bite at the cake, and yet another, till no more was left. When Gip saw the last bite disappear, he gave a long howl of disappointment that Horace did not understand in the least.

“That’s right!” he said. “You don’t believe the world’s round, do you. Guess I won’t go back to school any more.”

He started to peel the orange, and began to think hard.

“Let’s be partners Gip!” he said, “and explore. Let’s find out if it’s true—this about the world. Let’s walk to the edge of it and look over. They say England is on the other side. Will you be partners, Gip?”

Gip was always willing to be Horace’s partner, especially when cake was about—though he found his master did not share evenly at all. Still, he was willing to go anywhere with Horace, and hope for the sharing part. Besides, he did not approve of school for Horace, any more than Horace himself did, for the dog had to spend many lonely hours without him.

“To-morrow,” said Horace, “we’ll start on our journey—and to-night I’ll prepare our luggage. We won’t need much. Just plenty of food. I’ll put a good few oranges in for fear I get thirsty—because you can drink anywhere.”

Gip wagged his tail again, as if in entire approval.

The next morning Horace set out for school as usual. He had his satchel on his back, but alas! that satchel was not filled with books. It contained oranges and cakes instead, and when he came to a certain path that led to the school, he passed it, and went on till he came to a path that led to the bush, which he turned into.

“This is better than school,” said Horace, after a while. There were so many things to interest him in the bush—birds twittered among the trees, and here and there a bunny raced across the path. Kookaburras laughed everywhere, and the sun shone through the trees from a cloudless blue sky. It was an ideal day on which to try and discover the “edge of the world.”

It was not very long before Horace began to feel hungry, but that did not trouble him much. He had plenty of oranges and cakes, and biscuits—also a bottle of water. Gip welcomed dinner-time with “en — thusi — as — tic” wags of his tail — at least that’s how Horace explained it when he grew older.

While they were eating their dinner, two or three bright-eyed birds hopped about, and Horace threw them a few crumbs. Presently an old Kookaburra came and sat on a branch of a tree near to them, and started to laugh long and loudly.

“Ha — ha — ha — ha — hee — hee — hee — hee — hoo — hoo — hoo — hoo — hi — hi — hi — hi — haw — haw — haw — haw —”

“What are you laughing at?” asked Horace at last.

“You — you — you — you —” continued the Kookaburra.

“What is funny about me, Jack?”

The Kookaburra stopped laughing, and flew down beside him. He did not seem a scrap afraid of Gip — and that faithful doggie, not feeling hungry so soon after dinner, just lay and watched him.

“You want to find the Edge of the World, eh?” said Jack.

“Yes—”

“Well, you can’t find it just walking along like this.”

“What shall I do then?” asked Horace.

“Either get a balloon, or — find the White Rabbits’ Geography Book,” said Jack.

“Where shall I get that?” said Horace.

“Ask me something easy — I’ve been trying to find it all my life. If I could only find the White Rabbits’ Geography Book. I — I — would not have to laugh any more — and then nobody would call me a Laughing Jack Ass.”

“Can’t you give me any directions,” asked Horace.

The Kookaburra hopped nearer — and lowered his voice to a whisper. “I’m the White Rabbits’ enemy — they think — and, of course, won’t trust me out of their sight. I’ve been trying to get that book for years — and years — ha — ha — ha — ha — he — he — he — he —”

“Hush!” said Horace. “There’s a White Rabbit coming up the path now.”

Whereupon the Kookaburra whispered, “Do your best — and I’ll help you with the rest,” and then he scrambled under the flap of Horace’s school satchel among the oranges. Meanwhile the White Rabbit was coming up the path — and Horace shouted:

“Hi — just a moment. Could you tell me how to find the edge of the world?”

“In the White Rabbits’ Geography Book you’ll find directions.”

“But where am I to find the book?”

“At the foot of the oldest gum tree in the bush you’ll find a little door. Here’s the key. Return it to the next White Rabbit you see.”

“Ha — ha — ha — ha — hee — hee — hee — hee —” started the Kookaburra, making the White Rabbit jump with fright. Then he squeaked to Horace, “Give me back that key. You are partner with a Kookaburra —”

“No!” said Gip suddenly waking up. “Indeed no! He’s my partner. He was only talking to —”

“Hush!” said Horace. “I haven’t seen a Kookaburra.”

“Yes. you have,” said the Laughing Jack Ass. “Give me that key,” and he flew out and plucked the key from Horace’s hand. The next moment they heard him laughing at them from the highest tree in the Bush. “You — you — you — you — must — must — must — must — not — not — not — not — tell — tell — tell — tell— stories,” he cried. “Ha — ha — ha — ha!”

The White Rabbit was nearly mad with grief — and sobbing disappeared into the bush — the only thing one could expect a rabbit to do in any crisis. Suddenly Horace became conscious that the moon was rising up over the trees, and that the sun had gone to bed.

“What is the meaning of this?” he asked himself, and looked round for Gip. That bright partner of his had gone, and all the cakes in the satchel were eaten up.

“When I get home I’ll give that young scamp something to remember,” he said to himself.

All at once it flashed over him that he had fallen asleep after dinner, but he couldn’t decide whether the Kookaburra, and the White Rabbit and the Key were dreams —because you know there are so many Keys and Kookaburras and Rabbits in Australia, that it could easily have not been a dream. Suddenly a loud, long Coo- ee” rang out through the bush. Horace listened intently, until another “Coo-ee” sounded. It was his father’s voice — and he answered with a shrill Coo-ee.

Tramp — tramp — tramp through the bush he heard footsteps coming nearer, and he rose to meet his father.

“Why did not you go to school to-day — you naughty boy,” were the first words that greeted him.

“Because I wanted to find the Edge of the World,” answered Horace, thinking it best to tell the truth this time; “but that Gip deserted me. I’ll give him —”

“Don’t you,” said his father. “That dog saved your life. Ran home and told us all about it, or you’d have been lost for ever.”

As Horace walked home beside his father he could not help thinking how thankless is an explorer’s life — but like a true “explorer” he determined that the quest for the “edge of the world” was not ended, and that he would take the Kookaburra’s advice and set out in a balloon next time, and also leave Gip at home.

At present he is back at school saving up for the balloon, and they are still trying to teach him that the “world is round.”

This site is full of FREE ebooks - Project Gutenberg Australia