a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

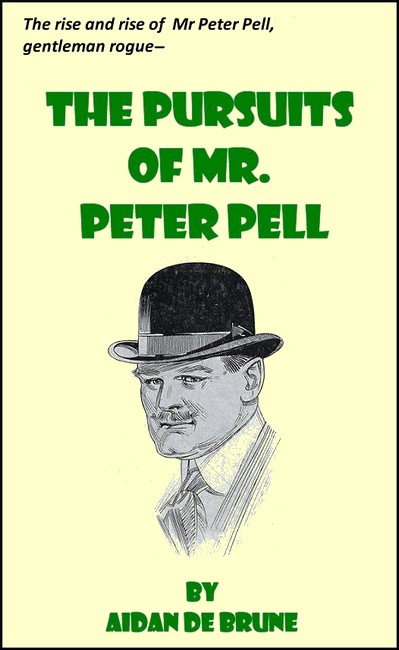

The Pursuits of Mr. Peter Pell:

Aidan de Brune:

eBook No.: 1701171h.html

Language: English

Date first posted: Oct 2017

Most recent update: Jun 2021

This eBook was produced by: Terry Walker, Colin Choat, Gordon

Hobley and Roy Glashan

by

Aidan de Brune

(Writing as Frank de Broune)

The Pursuits of Mr. Peter Pell.

Cover designed by Terry Walker©2017

THIS book is a product of a collaborative effort undertaken by Project Gutenberg Australia, Roy Glashan's Library and the bibliophile Terry Walker to collect, edit and publish the works of Aidan de Brune, a colourful and prolific Australian writer whose opus is well worth saving from oblivion.

THE first beams of the morning sun wandered across the Esplanade and, penetrating a leafy screen, fell upon the closed eyelids of Mr. Peter Pell. That gentleman opened one eye slowly and then closed it quickly, but the sun was not to be denied and, at last, it dawned upon the awakening senses of Mr. Pell that it was time to be up and about.

It was not the first time that the exigencies of modern civilisation had forced Mr. Pell to seek an airy couch on the playground of the Perthites. By choice he was sybaritic, by necessity ascetic, but yesterday evening it was a choice between supper and bed and the vanities of the table proved superior to the claims of bodily repose.

Mr. Pell, rising from his hard couch, showed what ladies of a certain age and standing call "a fine figure of a man." He was largely made with even a slight tendency to stoutness. His head was somewhat small and set on his head at an angle that gave him, when excited, a certain air of ferocity. His hair was thin, although covering nearly all the top of his head.

His voice, his principal asset, was heavy and boomed like the tenor "C" of the cathedral chimes. For preference he was clean-shaven, but on this morning his toilet had been neglected and he showed a two-day growth of beard on chin and lip.

Dispensing with ablutions, Mr. Pell carefully dusted his clothes and then considered his position. The first, and from internal reminders, the most pressing necessity was for breakfast. A search of his pockets revealed, or rather confirmed the knowledge, that the balance in hand consisted of one penny and three half pennies.

Balancing each coin on a separate finger Mr. Pell gravely considered them. Certainly breakfast commensurate with his requirements was not compassed within the ability of twopence halfpenny. Some sort of food might be obtained for sixpence, but even that, sum was not to hand and Mr. Pell's ambition lay in the direction of a regular thoroughgoing breakfast, beginning with the usual porridge and continuing through eggs and bacon, chops, steaks, etceteras, to the grand finale of bread and butter and marmalade. At the thought of the last item Mr. Pell's tongue gently inserted itself between his lips for he had a very sweet tooth. But, however elastic his thoughts, twopence halfpenny was but too matter of fact.

Somewhere in this gay city of Perth, thought Mr. Pell, there must be come kind friend from whom the necessary coins of the realm may be obtained to provide for the realisation of the Epicurean feast.

Leaving the Esplanade Mr. Pell made his way to Hay Street. Assuming the air of a moneyed loiterer, he carefully examined the goods in the shop windows, at the same time keeping a careful eye open for some acquaintance who might prove financial. The hurrying crowd of workers and shoppers jostled him, but nowhere did he see a familiar face.

"Hullo, old chap!" A voice, sounded in his ear and a heavy hand descended on his shoulder. Mr. Pell swung round with hope in his heart.

"Just the man I was looking for." The accoster was a thin nervous looking man with a vacant wandering eye and a ragged beard. His appearance was unkempt and Mr. Pell could not place him on his list of acquaintances and friends. But it was evident from the other's manner that they were acquainted, while Mr. Pell's memory might be defective, and breakfast loomed as a possibility.

"My dear fellow," retorted Mr. Pell, unctuously. "I am pleased to see you.—What—"

"I'm in a little difficulty," interrupted the stranger in a hoarse whisper. "Could you—would you—permit yourself to do me a favour?"

"Well, er—" commenced Mr. Pell.

The stranger interrupted quickly. "My dear sir, I am sure you will do your best for me. You know of old how diffident I am of speaking of intimate, I may say family matters, to an acquaintance. But you and I are, I should say have been, so intimate that I feel I may speak to you as a brother. My request is a small one, so small that you will, I am sure, have no difficulty in helping me. Can you? Will you? I am sure I have but to speak and your great heart will immediately respond, lend me half a crown for a short period. Stay! Do not speak hurriedly The loan, trifling as it is, will be repaid to you with the utmost promptitude, and perchance, when circumstances have altered, when I assume the rightful position to which I am entitled, your affairs will have my complete and sympathetic support."

Into the thin mist of the early morning vanished Mr. Pell's hopes of an immediate breakfast. Here was another on the same expedition as himself. Yet never in his life had Mr. Pell failed to rise to the occasion and now his tones were urbanity itself.

"My dear sir! I am most sorry. I am deeply grieved. Owing to the fact that, very unfortunately, I left home this morning without my purse I am—er—in somewhat similar straights to yourself. If you will do me the favour of meeting me after—er—my bank opens er—I shall be pleased to comply with your request. Until then, au revoir."

With a graceful sweep of his hand Mr. Pell slowly faded down the street The interruption had only emphasised his need for refreshment. The morning hours were speeding fast and the opportunity of obtaining a loan from some business acquaintance would soon be lost.

Murray and Wellington Streets proved barren hunting grounds and Mr. Pell turned the corner of Barrack Street, his hopes of a luxurious breakfast fast dwindling. The Town Hall clock struck the hour of nine. From the direction of the Terrace came Matt Horan driving his well-known pacer 'Laughing Bill.' He was driving at a good speed, but on seeing Mr. Pell quickly pulled up.

"Hullo, Peter." Now if there was anything that disturbed Mr. Pell's equanimity, it was to be addressed as 'Peter.' He had a very serious opinion of his own importance, and for a person of his commanding figure to be so familiarly addressed showed, in his opinion, a disregard of the due observances of life. To be addressed as 'Peter' was sufficient to destroy even a man's illusion in himself. For these reasons Mr. Pell turned a deaf ear. But Horan was not to be denied.

"Hey, Peter—Peter Pell!" Horan was a persistent person and on second thoughts Mr. Pell thought it wise to answer to the call. Besides it is not always welcome to have one's name thundered in the streets for all and sundry to hear.

"My dear Mr. Horan," said Mr. Pell, advancing to the jog-car with all the dignity he could assume while breakfastless.

"Come off that 'oss, old pal," retorted Horan. "Got anything on?"

Mr. Pell looked down at his attire. It certainly was not of the best but, in his opinion, sufficient for decency.

"At the present moment my time is not occupied, if that is what you mean," replied Mr. Pell with great dignity.

"Jump in, then!" Horan moved up in the seat.

"Into that!" Mr. Pell's voice had a note of anxiety. "I am afraid, my dear sir, that my—er—"

"Oh, you ain't as heavy as all that. But please yourself. Got a job that might suit you if you're on; if you ain't, so long." Horan made a move to drive off.

Again Mr. Pell saw his breakfast fast escaping him. Leaving his dignity to be assumed when his bodily needs had been attended to, he mounted besides his friend in the frail cart.

"It's this way, Peter," commenced Horan, as the pacer moved suddenly into gait. "I'm at the end of my wits to know what to do. This 'ere 'orse is great. I'm open to acknowledge that. The question is, is 'e great enough to win the Christmas Cup. I think he is."

"He is a very large horse, so far as my judgement can be relied on," replied Mr. Pell, looking critically at the quadruped under discussion.

"Oh, get off! What I wants to know is, is he going to pay me to win the Christmas Trotting Cup."

"My dear Mr. Horan," replied Mr. Pell with some warmth. "How should I know? He certainly is a very fine horse so far as I can judge, but I must acknowledge to a very slight knowledge of horses, and especially of trotting horses. To some extent therefore my opinion must be valueless."

"Jest so! If you knew a horse from a cow I wouldn't have brought you into the game. The question is, are you open for an offer."

"Of what?" For the moment Mr. Pell was startled.

"To put this 'ere 'orse right in the books."

"I don't quite understand you," said Mr. Pell dubiously.

"This 'ere 'orse is the great tip," explained Horan.

"Does he?" asked Mr. Pell, innocently.

"What?"

"Tip."

"Good lor'!" and Mr. Horan looked at his companion with a certain amount of admiration. "Are you as innercent as all that?"

"I quite fail to understand your meaning." Mr. Pell had again obtained a grasp on the situation, although he kept a very tight grip on the side of the cart.

"You're the boy for my money. Keep it up, Pell, and you'll pull off the trick."

"Again I quite fail to gather your meaning." A hazy impression that his companion was making fun of him floated into Mr. Pell's mind.

"Never mind understanding, Pell. Are you on?"

"On what? Certainly not on that horse."

"Who's a-askin' of yer? Look 'ere, Pell, will you do as I ask, or will yer get down?"

Again the breakfast for which Mr. Pell was valiantly struggling faded into the distance. Bewildered with the rapid motion and the phraseology of his companion he muttered something that the other took for an assent.

"That's the ticket! Now what I want is why can't I get a decent price about this 'ere 'orse, and it'll take someone as hinnercent as yerself to do it."

"Will you kindly inform me how I am to start about the delicate negotiations with which you have entrusted me."

"All in good time, old buck. Here we are, and the missus has the breakfast ready. In yer go an' I'll put you wise after."

The pacer swung into the yard and Horan threw the reins to an expectant boy. From the house came a pleasant odour of cooking.

Mr. Pell was fed almost to repletion, for Mrs. Horan was a good and generous cook. Smoking one of Horan's black cigars he followed that worthy into the yard to receive his instructions: The conference was a long one, and in spite of his absolute ignorance of the sport of trotting, Pell began to be interested in the matter. Besides, there appeared to be a possibility of a certain amount of cash finding its way into his pockets, and that was a matter on which he had strong convictions.

Fortified with a large breakfast and primed with, to him, a mass of somewhat vague instructions, out of which the central idea stood out plainly, Pell took a dignified farewell of his host and started to walk back to the city. Half-way he stopped in self-disgusted amazement. Absorbed in the delicate negotiations entrusted to him and the wealth he would acquire if successful, he had quite forgotten to obtain a temporary loan from Hogan to provide for immediate necessities.

For the moment he had thoughts of retracing his steps, but old experience told him that Horan was a generous payer by results, while he was one of the most difficult men to extract a loan from. He decided to go on and trust to his luck.

With his fingers round the four insignificant coins in his pocket he stepped out citywards, his thoughts filled with the wealth that would be his in the near future.

Midday on the Terrace is a good time to encounter the sports of the city of Perth. There can be seen the owner, the jockey, the bookmaker and the sportsman. The latter is an indefinable specimen of modern civilization that discounts the wisdom of the ages. He toils not, neither does he spin, yet Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed as one of these. To be particular, none of them seem to lack cash, and many indeed can produce a roll of those dirty-looking crumpled notes that do duty in Australia for the British sovereign.

Mr. Pell joined the group that is always to be found supporting the walls of the United Service Hotel. Introductions are not enforced in this branch of society, and a chance word or two, professing a knowledge he did not possess, one of the many phrases of Horan, coupled with, a clever reference to that gentleman, soon gave Mr. Pell his favourite position, the centre of the limelight.

"My friend, Mr. Horan," he commenced.

"Oh, Horan!" someone in the crowd ejaculated disdainfully.

"My friend, Mr. Horan, the owner of 'Laughing Bill' repeated Mr. Pell with emphasis.

"'E's the winner of the Cup," interrupted a short thickset man. "Per'aps 'e will, per'aps he wont."

"Goin' to win it yerself?"

The conversation was gradually drifting away from Mr. Pell.

"Mr. Horan said to me this morning—" Our worthy was determined to be heard and had raised his voice slightly.

"If Horan said 'is prayers it's all 'e did say," said the short man with emphasis, "'E's the closest cuss I've ever had to deal with."

Mr. Pell had another try.

"Mr. Horan gave me to understand at breakfast this morning that 'Laughing Bill' could not possibly lose the Cup."

"Did he now," the short man was openly derisive, "and what may I ask did 'e charge for the professional advice?"

"'Laughing Bill' did 34 the other day. I 'ad the watch," interjected one of the crowd.

"Wot's that! 'Pretty Pride' did 27 to the mile in the last Christmas Cup, an' she's on scratch this year."

"An' wot about 'Saucy Sam'? Why 'e did 18 the t'other mornin," I timed 'im meself, and 'e's honly 10 behind ."

And so the discussion bandied from one candidate for the big race to the other. Mr. Pell walked away well satisfied. He had carried out his instructions to the letter. Before he had gone far a grimy hand was placed on his cuff.

"'Ave yer much on th' 'orse yerself, sir?"

A small wizened man with 'hanger on' written all over him was the enquirer.

"Only a few hundreds, my man," replied Mr. Pell with dignity, "but my affairs cannot possibly interest you."

"Perhaps not, sir," replied the man humbly, "perhaps I might be able to 'elp a gentleman who might 'elp me."

Mr. Pell swelled with importance. "In what manner do you suppose you could be of assistance to me, my man?"

"It's this way, sir. It may 'appen that I may come across some hinformation that might be useful to a gent such as yer. An' if so, a gent such as yer might feel grateful."

"In such an event, my friend," Mr. Pell rattled the few coins in his pocket, "I should be extremely grateful."

"There might he a bit a-comin' now," insinuated the new acquaintance.

"There will he nothing coming until the information," said Mr. Pell emphatically.

"There ain't no flies on yer, now, is there," said the man with grudging admiration. "Well, so long till temorrer. I'll tell yer what's wot then if yer'll meet me 'ere."

Fingers in his waistcoat pockets, his chest well thrown out, Mr. Pell strolled along the terrace to the William Street corner. Pausing to survey the scanty traffic, Mr. Pell retraced his steps. Outside the United Service Hotel he found, as he had expected, Sol Arrons, the well-known and highly respected bookmaker. While he had been talking to the 'sports' Mr. Pell had noticed the bookmaker listening.

This time Mr. Arrons stopped him. "Excuse me my friend," Mr. Arrons placed a finger, that sadly needed the services of a manicurist, on the breast of Mr. Pell's coat. "Excuse me, but have I not the pleasure of your acquaintance?"

"Have I?" said Mr. Pell, gently removing the finger. "Yes, I believe it is Mr. Arrons! And what can I do for my worthy friend?"

"I have heard you talking this morning of the 'Laughing Bill' is it not so?" said Arrons, peering up into Mr. Pell's face. "Ah, I thought I guessed right. And, perhaps a fine gentleman like you, might like to have to have a little bet with old Arrons, on the fine horse. Just one little bet with old Arrons. Fine gentlemen like to bet with old Arrons."

Mr. Pell tried to look disdainful, and failed. He had angled and caught his fish. Let Arrons swallow the bait he had nibbled at, the bait that Mr. Pell had dangled along the Terrace for the last hour, and the work was accomplished. Mr. Pell would have his pockets filled again.

"Perhaps I might like to have a pony later, Arrons," he replied as indifferently as he could. "If so, I will not forget you."

Arrons fairly cringed. "It is good of you to say so," he fawned. "But why not now? I will give you a good price, an excellent price. I will—yes—I will be generous to you, my dear friend—I will give you two to one. Just think, two little sovereigns for one little sovereign bet."

"You what?" queried Mr. Pell.

"On the 'Laughing Bill.'" Arrons appeared slightly astonished at Mr. Pell's tone.

"No good to me," said Mr. Pell emphatically. "In fact I do not think I will back the horse at all."

"But you are a friend of Mr. Horan's. You have the knowledge of what the horse can do. You were with him this morning, and he told you to back it."

"Perhaps that is the reason I will not bet." Mr. Pell tried to look wise.

"You will not bet!" Arrons was excited now. "You have the information. But I forget. It is dry for a gentleman to stand and talk. You will come and have a little drink with me, and then you will tell me what it was that our friend Horan said to you when you had breakfast with him. Ach, is it not?"

Mr. Pell condescended to take a drink at the expense of Mr. Arrons, to the amazement of the habitués of the Hotel, who strove vainly to remember a previous occasion on which Arrons had 'shouted' anyone a drink. After the drinks, Arrons steered Mr. Pell into a vacant corner of the room and busied himself with the pump-handle.

Mr. Pell responded nobly. He leaked information while not appearing to do so. In fact, his appearance was that of a man who strove vainly to retain a valuable secret entrusted to his charge. With many expressions of goodwill, Arrons parted with his friend.

Fingering five coins in his pocket, Mr. Pell sauntered towards Hay Street. Stopping before his favourite restaurant, he took out of his pocket a yellow coin that glittered in the noon sun.

"There is something in this racing game after all," observed Mr. Pell to himself, with a sigh of satisfaction.

IF a house be searched, however careful the housewife, there will be surely found, in some odd nook or corner, a cobweb. So in most cities of the world there are to be found, in the odd corners, traps for the unwary human flies. Tangarten Chambers, on the "Terrace," has an imposing position. Most of the chambers are inhabited by members of the legal fraternity. But there are others, and of the others is to be numbered Mr. Peter Pell.

Pell had "arrived" since the day when the sun, on its daily pilgrimage, had discovered him in his Esplanade bedchamber. A lucky deal with the Terrace "odds-shouters," in which those gentlemen had not displayed their accustomed acuteness, had resulted in Mr. Pell becoming the owner of a fair banking account. Success had bred encouragement, and Mr. Pell blossomed out as a Land and Estate Agent.

It is sad to reflect that a business connected with so dignified subjects as Lands and Estates should be the mantle for so many rogues. Yet it is a fact that if a bad man sets out to fleece his fellow men commercially, it is usually under the cloak of a Land and Estate Agency.

In the case of Mr. Pell, that gentleman would have been puzzled had he been required to find a client anything in the shape of an estate, or even a small block of land. Notwithstanding this minor drawback, the office was there and the door emblazoned with the titles of the business Mr. Peter Pell was willing to undertake.

As in the case of the cobweb in the house, so the net that Mr. Pell set for the fly he was confident one day he would snare, was set in an inconspicuous part of the inscription. It was a bare and innocent web and announced quietly that on the other side of that door were the offices of the "Great Fallgall G. M. Syndicate."

Within the office Mr. Pell had done himself well. The carpet on the floor, the large roll-top desk and the client's chair, all bore an appearance of wealth. Mr. Pell was resplendent and would have inspired confidence in the most wary of city men. With prosperity, or the semblance of it, Mr. Pell had indulged his taste in fine raiment to the fair. He affected the style of a London business man, frock coat, and something neat and classy in the matter of waistcoats. In the case of Mr. Pell, however, the waistcoat was classy if not exactly neat. Whatever the general taste may be, Mr. Pell fancied himself and grew more and more complacent as he gazed at the large expanse of waistcoat revealed by his office mirror.

The office of Mr. Peter Pell, Land and Estate Agent and Secretary to the Great Fallgall Gold Mining Syndicate, had been established for more than a couple of months, at the time our records open, and the proprietor had begun to study his bank-book with some misgivings. True one or two small flies had walked round the web but had, in spite of the genial welcome they received, contrived to back out of the trap without more than singeing their wings. In fact the total takings of the "web" had resulted in a paltry "fiver" while the expenses were large. Mr. Pell did not complain. He was prepared to "stick it out" as he, in a moment of confidence, stated to a friend, until the right kind of fly (he did not use this exact expression) had become entangled. To those who can wait, success will come.

One morning as Mr. Pell strolled in the direction of Tangarten Chambers he had an inspiration that that day would later be marked on the office calendar with a red circle. The sun was high in the sky and the majority of the business men of the metropolis were at their desks, but Mr. Pell did not hurry. Human flies are foolish mortals and have not the intellect of their winged confrères and if the human fly had noted the web for examination it was certain that he would buzz around until Mr. "Spider" Pell arrived. Therefore, without increasing his wonted leisurely pace, Mr. Pell entered the Tangarten Chambers and cordially, yet distantly, returned the salutation of the lift-boy. In the exigency of existence Mr. Pell had fully realised the potentialities of his fine presence and developed the art of taking full advantage of it. But after a few months on the register of the tenants of the Chambers he had become one of notabilities of the building, in the eyes of the attendants. A few cigars, a very little silver, and the trick was done. Mr. Pell, with his tips at the wrong seasons of the year was "it."

Arriving at the third floor, Mr. Pell withdrew from his trouser pocket, by a silver chain that in size might have done duty for the cable of a rather large toy man-o'-war, his office key. Directly facing the lift entrance was the office of the Great Fallgall G. M. Syndicate and standing at the door with all signs of impatience stood "The Fly."

Too wary to frighten his prey, Mr. Pell opened his door and strode to his desk. The "Fly" meekly followed him. Without speaking, Mr. Pell opened his letters and indulged in a running commentary on the contents. It might be as well to explain here that these letters had been carefully prepared by Mr. Pell some time previous and were nightly placed on the desk in preparation of the visit of the "Fly." Here was the victim, and the spoiler was ready and eager.

"Humph! Great Fallgall's up two points! Sanders wants to know if any for sale! No none for him! Ho! So Matthews has made up his mind to buy that house at last. Well he'll have to pay for the delay. He'll spring another tenner if I hold off a bit. The cheapest house in the State. What's this! Application for Great Fallgall shares. Another! Yet another! And another!!! Let me see. Five and ten are fifteen and ten hundred shares in one post are twenty-five! Twenty-five good business!"

Then, thinking the "Fly" properly impressed, "Oh, beg pardon! Didn't see you there. Come in, sir, make yourself comfortable. Sit there. Now, tell me what I may have the pleasure of doing for you?"

As the "Fly" seated himself gingerly in the client's chair, beside the big desk, Mr. Pell took careful stock of him. He was a tall thin man with a long gaunt face. His clothes were untidy and looked ready made, but his boots were the true index to the man, and, on a rapid survey, Mr. Pell ejaculated under his breath, "Farmer."

A London spider would have profanely thought "yokel" but in Western Australia the commercial spider is not so rude and unpolished. He dignifies the "fly" from the country by the correct appellation "farmer." It is not to be understood that "yokel" or "farmer," there is any change in the established methods of spiders. Both London and Perth spiders treat the country visitors alike. Flatter and toady; tickle and excite. But, in the end, skin them or swallow them alive.

Mr. Pell prepared to do both. The "Fly" prepared for the interview by extracting from a large case a pair of the largest and roundest spectacles Mr. Pell had ever seen. Perching them on a very long thin nose, he proceeded to state his requirements.

"My name is Smith, Joseph John Smith," he commenced in a high nasal drawl. "You are the proprietor of this Great Fallgall Gold Mine."

"Only the secretary," replied Mr. Pell modestly. "The proprietors are umph—It is owned by a Syndicate, you know!"

"Pre-cise-l-y," drawled Smith. "You are the secretary." Then after a short pause came the question like the shot from a gun.

"You sell the shares?"

"The Syndicate sells the shares," replied Mr. Pell smoothly, wondering all the while what on earth his visitor was driving at. "I am but the humble servant of the Syndicate."

"Pre-cise-l-y!" drawled Smith in exactly the same tone. Then a change of voice. "You cannot deceive me."

"My dear sir!" Mr. Pell was horrified at the suggestion. "All the dealings of this office are open to the widest, I may say the fullest, investigation."

"That is what I intend, sir," exclaimed Smith, ferociously. "I received one of your circulars."

"Prospectus," suggested Mr. Pell mildly. "It sounds so much better."

"Bosh!" exploded Mr. Smith. "If I come from the country I am not a born fool."

Mr. Pell tried to look hurt and really achieved a fair success. "I have come to investigate this matter to the ground, and if I like it—" here Mr. Smith sank his voice to an impressive whisper, "I will buy it."

"Buy some shares?" asked Mr. Pell, for once out of his depths.

"Buy the mine—all the shares—the—er—controlling interest, sir," howled Mr. Smith with all the semblance of fury.

"That would be a very expensive operation," suggested Mr. Pell, his heart sinking at the thought that his visitor was more madman than "Fly."

"Expense, be damned," retorted Mr. Smith, leaning forward in his chair and glaring at Mr. Pell through his large round glasses. "Do you know who I am?"

"I—er—I'm sure I don't know." Mr. Pell's imposing waistcoat was visibly curving in at the waistline, and his collar appeared to be undergoing some liquefying process.

"I'm Joseph John Smith, and I breed sheep?"

Mr. Pell made an effort. "You can't buy shares like you do sheep, Mr. Smith."

"Why not? Tell me why not. I've made my money in sheep. Lots of it, lots of sheep. Why can't I buy anything I want as I buy sheep. Tell me that."

"It will be a very expensive operation, Mr. Smith."

"Did I ever shirk an expensive operation? Ask the people of the Gascoyne if any deal was too big for me. I'm a born Australian, and nothing's too big for me."

"It will take a lot of money, Mr. Smith." Mr. Pell tried hard to discover what ground he had to stand on. Either his visitor was a clever business man, or into the web had walked one of the fattest, juiciest flies that ever spider dreamed of. What dare he put up to this glorious prey?

"I may tell you Mr. Smith," Mr. Pell continued, "that the mine is undeveloped. We have taken out very fine specimens, sufficient to show great possibilities. I don't want this information round the town, but we have the very deepest, richest mine in the whole of the Commonwealth. It will take a lot of capital to obtain the controlling interest."

"Name your figure!" The large horny hand of the visitor moved to his breast pocket.

"Not that, Mr. Smith." Mr. Pell waved the thought of a cheque aside with a magnificent gesture. "Not that! We must go into the matter a lot more carefully before I can venture to accept your cheque."

Joseph John Smith extended the hand that hovered around his breast pocket in the direction of Mr. Pell.

"Shake!" he exclaimed. "You're an honest man."

Fortified with the good opinion of his visitor, Mr. Pell devoted himself to posting his prey in the details of the Great Fallgall G. M. Facts and figures rolled from his tongue in a manner that would, as a writer of fiction, have assured him more than a competence. As a walking delegate of a trades union he would have been an unqualified success.

"It comes to this," concluded Mr. Pell. "It will cost you about three thousand pounds or thereabouts to take up the balance of shares in the possession of the Syndicate, and about fifteen hundred more to repurchase the balance of shares necessary to give you the control."

"Is that all?"

"I am afraid, so." Mr. Pell was disappointed. He felt that fate had used him unkindly in not instructing him more fully of the tender morsel prepared for his detection.

"Will you have the cheque now, or wait till you get it?"

"Wait until I get it," promptly exclaimed Mr. Pell. Again a doubt arose in his mind as to the fallibility of his "Fly." Was he to discover after all his work that the "Fly" was in reality a brother "spider"?

"Spoken like a man!" exclaimed Smith with satisfaction. "Now—" and again the horny hand moved in the direction of the breast pocket.

"My dear sir!" Mr. Pell stretched forth a detaining hand. "I could not think of such a thing. You must examine. You must enquire. You, sir, may deem me to be an honest man, but others may think otherwise. I have enemies. What successful man has not. You must enquire. I insist you must satisfy yourself that Peter Pell is the honest man you now think him."

"That's all right, my boy," exclaimed Smith genially "I ain't dealt with men up north to be taken in by a town shark. Don't you think it."

"Your candour does you credit, sir, and touches my heart." Mr. Pell produced a very fine pocket handkerchief and vigorously blew his nose. He felt that a tear would be a great relief, but had not the power to raise one. He would have much preferred a laugh.

"Look 'ere, Pell." Smith leaned forward in his chair and laid his hand on the well turned leg of Mr. Pell. "Take that cheque."

"No." The monosyllable was decisive.

Smith looked keenly at Mr. Pell. "I thought you wouldn't! You wouldn't have got it if you had said 'yes.' I ain't no fool, and its only fools that pay the price asked 'em for the goods. Now I'll make you an offer."

"Sir!" exclaimed Mr. Pell—the fly was walking right into the trap and in a moment the door would shut behind him. "Sir, I will give to your offer my gravest consideration, but you must remember that I am only the servant of the Syndicate and they must determine your offer. My word," here Mr. Pell swelled visibly—'carries great weight with the Syndicate. I would deceive you if I let you think otherwise. And that word will be used in your favour, of course, providing your offer is commensurate with the value of the mine. But I am afraid—I am afraid—" and Mr. Pell's head rolled gently on its fleshy support.

"Well then!" Mr. Smith sat upright with a visible jump. "Tell your Syndicate, or whatever you like to call them, that I will give them two thousand pounds for the whole concern, lock, stock and barrel."

Mr. Pell stared. Two thousand pounds! And that for a piece of ground that, if it held gold, still retained the secret. Certainly the ground was there. He, himself, had taken over the mining rights from a hard up friend some month or more ago, but he had never seen the property and, from what he had heard, gold had not been discovered within many weary miles of the location.

Two thousand pounds! His tongue gently inserted itself between his lips tasting the sweetness of the offer, for Mr. Pell had a fancy for the sweets of this life. Two thousand pounds! His eyes dropped to the large expanse of fancy waistcoat of which he was so proud. What fancy waistcoats could be not design and buy? Two thousand pounds! The world had been well lost for less.

"And," went on the voice of the fly, "for yourself, if you bring off the deal, there is a little packet of notes that might—mind I say might—total about two hundred and fifty. You'll put it through, Pell."

Mr. Pell's tongue stuck to the roof of his mouth. Two thousand two hundred and fifty pounds. British, Australian, English notes, call them what you please. It required a supreme effort on his part to regain his composure.

"Sir!" and the rich round voice rolled through the small office, "your offer as a bribe, I repudiate with indignation, with scorn. But—but as the offer of a friend, I should say, as a little testimonial to my integrity, and—and—business capacity—" even Mr. Pell could not leave it entirely to 'integrity,' "—it would be valued and esteemed."

"Say no more," replied the 'Fly.' When?"

Mr. Pell would gladly have shouted "Now!" but prudence forbade. With the greatest control he could muster, he stated, "I shall have to call a meeting of the Syndicate. Shall we say the day after tomorrow?"

With a grasp of the hand that made Mr. Pell wince, the "fly" emerged from the web, leaving the "spider" to ponder. For some time after Smith had left, Mr. Pell sat at his desk, leaning an aching head on his hands. Barely could he realise what had happened. Here was a man, dropped apparently from the clouds with a pocket full of money, asking, nay begging, Mr. Pell to relieve him of some. Did the skies rain fools?

THE MEETING of the members of the Syndicate took place in Mr. Pell's office as soon as Mr. Pell could recover his mental equilibrium. Mr. Pell was in the chair. The reading of the minutes of the Syndicate was voted unnecessary on the motion of Mr. Pell, seconded by the same gentleman. As a matter of urgency, the acceptance of the offer of Mr. Joseph John Smith, of two thousand pounds for a block of land Mr. Pell had not, and did not want to see, was moved by Mr. Pell and seconded from the Chair. Let but the "fly" venture his nose in the web again and the trap would be sprung.

During the afternoon of the next day, Mr. Pell was called to the 'phone. The conversation was short and pithy, yet entirely satisfactory to at least one member of the connection.

"Well?" came the voice along the line.

"Right-ho!" exclaimed Mr. Pell. Ordinarily he was adverse to slang.

"Cheque?" was the next question that struck Mr. Pell's ear.

"Cash! Ten tomorrow!"

And then along the line echoed Mr. Pell's last lapse from the correctness of speech: "Right-oh."

The following day Mr. Pell handed over the Great Fallgall Gold Mine, together with all rights in the registered offices of the Company, to Mr. Joseph John Smith and walked forth, a man without an occupation. In his breast pocket reposed a neat rubber-banded wad of paper inscribed with the signature of the Commonwealth Treasurer. Behind him he left a new secretary to the Great Fallgall Gold Mining Syndicate, together with an office of which the rent was long in arrears, office furniture for which an Australian Chinese was indignantly demanding hire purchase, and a telephone that at any moment might become dumb, unless the Postmaster General was pacified. All he left behind, but his fancy waistcoat stood out like the guiding flame that led the Israelites through the terrors of the desert, and against that waistcoat reposed the sum of two thousand two hundred and fifty pounds.

In the weeks that followed, Mr. Fell often thought of Joseph John Smith. Surely he had, been the "Fly" of flies. Mr. Pell thought with sore impatience of the carefully baited trap he had prepared, and of its uselessness. Any old thing would have sufficed with such a "Fly."

Then one morning, as Mr. Pell was carefully absorbing the breakfast of two ordinary men, his eye was caught by a double column heading in the West Australian. It spoke of gold, not in the usual quantities wrung from reluctant mother earth but in buckets, pails, truckloads. Gold to be taken for the asking—by those who were lucky to own that valuable spot of this earth's surface. And the name of the mine was The Great Fallgall Goldmine Limited, with Mr. Joseph John Smith, Managing Director.

Mr. Pell laid the newspaper on the table with great care. One might almost have thought it breakable.

"Good Lord!" he ejaculated, "and he could have got that old hole off me for a 'fiver.'"

TO the man who has achieved, a period of relaxation is given. This is one of the customs of modern civilisation that is becoming an unwritten law. Thoughts, somewhat on these lines, occupied Mr. Peter Pell's mind as he strolled along Hay Street West, one fine March afternoon. He had succeeded. In the safe custody of his bank reposed two thousand pounds odd. It had been won by him, if not by the sweat of his brow, certainly by assiduous thought. That the man from whose banking account his present wealth had come had benefited to a greater extent mattered not a jot to Mr. Pell, and when to his memory occurred the time when he sought a hard and airy couch on the Esplanade, he thanked heaven he was not as other men.

It has been recorded that the afternoon was fine and it may be further noted that Mr. Pell's mental condition in every way matched the weather. He was at peace with himself and his fellow men. He had time and to spare on his hands, yet he did not intend to remain long idle. Far from that; already he was on the watch to again raid the wealth of the unwary. Not that he allowed himself to think of any future financial operation in that light; it was business, pure business.

Two thousand pounds is not wealth; Mr. Pell fully realised this. And he realised that into his system had entered a new interest. He desired wealth for what wealth would bring, large meals to sustain his fine commanding figure; wealth to bring to his wardrobe the fine raiment for which his soul longed—the radiant waistcoat, the smooth broadcloth. Then again he desired, as he surely deserved, ornamentation. Across his flamboyant waistcoat stretched a chain of fine gold. Already gold, in his mind, had assumed a minor place in the order of precious things. What was finer than gold? For a moment he thought kindly of a watch chain studded with diamonds. But from such desecration Mr. Pell's artistic soul revolted. A chain of platinum? Yes, that would serve to impress and it was not gaudy, but—

By what process of reasoning Mr. Pell's thought travelled from precious stones to Love (a capital "L" please) it is hard to say. Yet it must be recorded that on the top of the hill Mr. Pell stopped dead in his carefully considered walk, struck with the idea of love.

So far in his life—and Mr. Pell had attained the age of 53, just the prime of life, as he had informed his landlady that very morning—he had not considered the question of Love. There was certainly a fly in that ointment, for Love must be connected with Woman.

Mr. Pell had never taken women seriously in his life. Up to the fatal moment when, stopping in his walk at the top of Hay Street Hill, women had always appeared to be something apart from his life. Other men had sweethearts and wives. Mr. Pell had sung about them at sundry "smokers" when he could induce the organiser to allow him to favour the company with a musical effort, but the thought of women in so intimate a relation to himself quite took away his breath.

Yet there was something in the idea that appealed to him. The successful business man—and Mr. Pell had come to the point when he classed himself as a successful business man—was set off, or it might be said illuminated by, a wife. It would be pleasant to be able to invite some business acquaintance he desired to impress, to dine and spend the evening with himself—and his wife.

The thought quite took away his breath. Once accustomed to the thought of a wife, and it did not take the agile brain of Mr. Pell long to arrive there, the question arose, "Who?" Certain ladies of his acquaintance were swiftly passed under review. Only one of them nearly filled the bill. Mr. Pell had almost decided on the lady—getting to the point of engagement rings, when Cupid revolted. Modern science has quite done away with the belief in the God of Love. Yet the scientists have still to explain why, when a man of a certain age, say 53, determines on love, and a certain lady, something inside of him kicks, and kicks hard. Why is it that big imposing men marry little insignificant women, and large fine women look around them for a man they could squash in a hat box. Yet such is the case. Love is not logical, in fact it is most illogical. Towns are full of love's mistakes, long men and short wives, elderly women and young husbands, and all the variations of the intermediates.

Certain scientists have endeavoured to explain Love as a microbe. Others by a cell that reaches maturity at a definite age and attracts like cells in the opposite sex. Facts are hard things, and while the scientists fool themselves that they have satisfactorily explained the myth of the ancients away, the majority of people are quite content to place all the blame for the misfits on Cupid—it saves blaming themselves.

So, when Mr. Pell had reached the stage when his mind wandered over the ladies of his acquaintance, in the search of a suitable mate, the little god gave a cough and squirm, and another misfit was quickly fitted into human society.

Mr. Pell had stopped in his measured walk. He had also stopped immediately outside an open gate. In his vision of the future Mrs. Pell, he had half turned and faced the roadway. This was the opportunity of the god of Love's misfits!

"Fido! Fido! Come here, you bad dog. Oh, he will be lost!" It was a feminine voice and not by any means an unmusical one. In a moment of sanity Mr. Pell would have flown to the rescue, for gallantry was not the least of his accomplishments. Now, however, he was wrapped in the visions of his brain. But Fido had received his instructions from other than a mortal being, and he proceeded with the utmost promptitude to carry them out. He dived through the gate and between Mr. Pell's legs. That gentleman sat down on the pavement, hardly and emphatically, narrowly missing the cause of his trouble.

Mr. Pell was shocked—in a physical sense. A gentleman of 'fine' figure cannot hastily assume a sitting position without some disturbance of his mental equilibrium also. When he began to realise what had happened to him he also became aware of a lady bending over him. It was a lesson in self-control that should have had a wider audience. Mr. Pell's impulse on reaching the pavement with a certain portion of his anatomy had been to swear—and Mr. Pell had a choice collection of remarks in stock, most of them very suitable for the occasion—but the face of his fair assister caused him to bite them back so quickly that he wondered if he had bitten his tongue by the shock of the descent, or by strength of will.

"Oh, dear! oh, dear! I am so sorry! it was my naughty Fido. I hope you are not seriously injured!"

Mr. Pell gravely assumed an upright position. Even he, with his strict deportment, would not have described his movements as graceful. Gentlemen with 'fine' figures cannot spring to their feet wish the agility of youth, and it is debatable if they can fall with any more grace.

"My dear madam, pray do not distress yourself. I assure you I am in no way discomposed. Your fine terrier—"

"It is a collie," corrected the lady mildly.

Mr. Pell thought that his definition of the—ahem!—dog that had caused his downfall much more appropriate. There is something alike in "terrier' and 'terror' that was almost soothing, but he was too polite to contradict.

"Ah, yes, collie," he replied gently. "I am sorry I did not get a closer inspection of your pet."

"How nice of you to put it like that," cooed the lady. "Some men would have been furious at the poor dear."

"Madam, they would not have deserved the name of 'gentlemen.'"

Peter was himself again. Certainly his fair assistant was all that the heart of a man could desire. But a few words, and Mr. Pell felt a distinct fluttering beneath his pocket book.

"You must come into my house and let me brush you down," insisted the lady with gentle authority.

Mr. Pell now took his first survey of the house. It was certainly a fine house and must have cost at least four figures to buy—Mr. Pell reduced most of the material things of this earth to figures. It was her house. Mr. Pell looked again at his hostess. She was certainly as fine a figure of a woman as he was of a man. They would make a fine couple. Again the fluttering at his heart.

The lady led the way into a handsomely furnished sitting room and relieved Mr. Pell of his hat and stick. The next operation was with a clothes brush, and here there was a small trial of politeness that ended in Mr. Pell brushing his own clothing. The lady had yielded, and he could not but admire the graceful way in which she had bowed to masculine control. A perfect woman—a perfect wife. Again the fluttering!

The operations with the clothes brush having concluded, the lady suggested a glass of wine as a soother and strengthener after the shock. Mr. Pell could certainly not drink unless the lady gave countenance and encouragement. The lady was willing. There ensued a duel of courtesy. The lady went to the sideboard—it certainly was a handsome well-made piece of furniture—and poured out the wine into two generous glasses.

Mr. Pell then escorted her to a chair and returning, served the lady from a silver salver. The salver weighed pleasantly in his hands. Replacing the salver, Mr. Pell bowed gravely to the lady, who rose and returned the salutation. They then seated themselves. It was like a figure of some stately old-fashioned minuet.

The lady looked at Mr. Pell and was immediately struck with his "fine" figure. She sighed. "I am so glad it was no worse."

"Madam, it is the hand of fate that led me to felicity."

"Oh, sir."

Admirers of Mr. Pell must have noted that on no occasion had he been found lacking in speech. With so fair an incentive he considered—in examining the situation later—that he had excelled all former efforts. The lady was willing, and from the usual society small talk became almost confidential. She pleaded the drawbacks of a lonely life. Mr. Pell spoke of the hardships of the wealthy bachelor in lodgings, and the forwardness of landladies was delicately hinted at. The lady was sympathetic. Finally an invitation to call was given and accepted.

Considering the interview over his chop at the Savoy Grill Rooms, Mr. Pell noted the following points. First, the lady was a widow. Secondly, her name was Mrs. Pascoe. Thirdly, she was certainly well-off. Fourthly, she had an evident admiration for the stronger sex. Fifthly, she had most delicately, so very delicately, bewailed her hard fate in not having a masculine intelligence and arm to lean her burdens upon. At the thought of the masculine arm Mr. Pell's curved instinctively—and the waitress edged away quickly, and tried to look scandalised.

Men of commerce have many and devious paths to knowledge. Mr. Pell, as a shining light of commerce, soon attained a true knowledge of the circumstances in which the late Mr. Pascoe had left his widow. They were very satisfactory. Mrs. Pascoe lived in her own house. The furniture was her own. There were no Bills of Sale or other such uncomfortable legalities. And there were satisfactory and substantial gilt-edged securities to which the lady could lay undivided and unencumbered claim. Altogether Mr. Pell felt that Mrs. Pascoe was a lady that could be loved not only for herself, but for all she had. Again the fluttering behind his pocket book.

The first visit was followed by others. Gradually Mr. Pell lay siege to the fortress of the widow's heart. Carefully he encompassed her with the siege lines of his love. Valiantly he attacked the outworks, and one by one entered them and raised the standard of the Pells. Only the main bulwarks so far resisted. The lady was coy. She allowed her admirer certain small favours. The pressure of her hand at meeting and parting. The intimacy of the divided sofa. Once, joyful day, he was permitted to retain that small plump hand in his for five minutes, while the lady described with remarkable exactitude the last moments of the late lamented, never-to-be-replaced, Horace Pascoe. At the end of the pathetic recital he was privileged to offer his fine cambric handkerchief, with the neat, if somewhat prominent monogram, to catch the soft-shed tear.

That afternoon he walked home on air—at least he thought he did. Mr. Pell had well laid his campaign against the forlorn heart of the widow. But two months had gone and he had established his footing in the house of Pascoe. Already he looked upon a certain vacant peg on the hat stand as peculiarly his own.

It was while he was brushing his hair one morning, he determined that Mrs. Pascoe's coyness must be stormed. The lady liked him, nay, in the privacy of his bedchamber, Mrs. Pell dared to declare that she loved him. What were his feeling towards her? From the moment he had first seen her face bending over him with commiseration, and sympathy for his fall, he had considered himself a lost man—lost in the mazes of Love's wilderness. He could congratulate himself that he had in no way, in the siege of the widow, departed from the strict canons of courtship as be understood them. He must put his fate to the test.

A careless sweep of the brush, that revealed the fact that the bald spot he so carefully concealed from the public gaze was steadily enlarging, also reminded him that time stood still for no man. Could a bald man woo? Never! Then he must woo and marry before his baldness became too apparent.

Full of resolve, he waited until four o'clock that afternoon and then set out for the widow's residence. He knew he would be expected, for a decided hint had been given that all callers but himself would be denied that afternoon. As he entered the hall and gave his hat and stick to the comely maid in attendance, he eyed the hat-stand peg with a friendly eye. Perchance, when again he called, he would have a definite future right to, not only the peg, but the hat-stand as well. He did not intend to pander to widowly coyness once the fatal 'Yes' was spoken.

"So you have come—at last." The last two words fell very softly from the lady's lips.

"Dear lady!" Mr. Pell had once been a student of Charles Garvise. He raised the plump hand of the widow to his lips.

"I expected you." The lady was making the running with some vigour thought Mr. Pell, but one glance round the room stifled all doubts.

"I am in trouble and wanted so much the support of your business intellect. I wondered if you would call."

Mr. Pell led the lady to the accustomed sofa and bowed her to the seat. Then majestically he seated himself beside her.

"Would I allow the fairest lady in Perth to be troubled? Tell me what you desire and it shall be done." Mr. Pell had some idea this was a quotation, but it fitted very neatly.

"I have some money idle in the bank," continued Mrs. Pascoe with some hint of business ability, "and I thought of investing it in 'Great Fallgalls.'"

"No, no, certainly not." Mr. Pell's words came rushing out in a manner that quite startled the widow.

"Why, I thought the mine was quite safe. Do you know anything against it?"

By this time Mr. Pell had recovered his composure. The mention of the Great Fallgall G. M. had been something of a shock to him. It would never do for the future Mrs. Pell to have any shares in the mine he had once owned. There had gathered lately a suspicion in the back of Mr. Pell's mind that Joseph John Smith bad been a good deal less "flyish" than he had supposed.

"I think," said Mr. Pell, speaking with some weight, "I should advise something a little more gilt-edged."

"But they pay such little dividends." The widow pouted.

"But they are so safe, dear lady!"

"I like a little flutter," remonstrated the lady.

"And sometimes little flutters pay nothing, not even your capital." Mr. Pell spoke grimly. "I should not like you to fail in your investments."

"You are so careful of me," murmured the lady.

"Are you not made to be taken care of?" Mr. Pell was gradually screwing himself up to the proper pitch.

"Ah! dear!" It was but a sigh that issued from those fair lips. "Oh, my dear!" And the substantial arm of Mr. Pell fell from the back of the sofa and stopped at the ample waist, of the lady.

"What would you advise?" gently asked the widow not appearing to notice the encircling arm.

"A man!" Mr. Pell replied thoughtlessly.

The widow tried to look shocked.

"But I can't invest in a man!" she giggled.

"Why not?" Mr. Pell, like a famous French Emperor, was compelling victory out of almost disaster.

"How?" The widow was insistent.

"Men are made for husbands." Mr. Pell was stentorious.

"How nice!" Here the arm had tightened so that the widow could not but notice it.

"You mustn't do that!"

"Do what?" Mr. Pell happy in the knowledge that matters were going his way, grew quite playful.

"Put your arm around me, unless—"

The words of the widow were interrupted by the flinging open of the door, and the dancing entry of a little girl of about five years old.

"Please, I've come!" laughed the newcomer.

"Oh, you darling!" gushed the widow. "Come and give me a big, big kiss."

The baby danced across the room and stopped quickly before Mr. Pell and the lady. With a grave little curtsey she presented a bouquet of flowers to Mrs. Pascoe.

"Many, many, happy returns of the day, Granny," she said very properly, and then with a laugh and a blush flung herself into the outstretched arms of the widow.

"Granny!" Mr. Pell's air castles came tumbling about his ears. "Granny!"

How he got out of the house Mr. Pell could never afterwards explain to himself. That he escaped was all he knew. Granny! Surely never man was so hardly used in this world! And, as he wended his weary way to the lonely apartments he had that afternoon taken a mental farewell of, an absurd voice in his brain insisted that somewhere in the Prayer Book there was a clause that stated: "A man may not marry a Grandmother."

IT is a fallacy that work was made for man. Yet it is a common knowledge that the only man that can exist without work is the man in love. There is something in love, that permits the ordinary individual to neglect his work in the world, to neglect his food, his clothing, his very existence. The lover lives in a world of his own, peopled by one solitary individual of the feminine sex, with a chorus of white wings, golden harps and angelic halos.

Some people may quarrel with the confining of the attributes of the true lover to the masculine sex and the consequent elevation of the eternal feminine to the position of the worshipped. It is but stating a fact. Women are not good lovers. A woman will not neglect all the decencies and amenities of modern civilization for the privilege of pondering over the attributes of the adored—as seen through rose coloured spectacles.

Who has ever seen a woman among other women neglecting to scrutinise the dresses around her, bump into passers, neglect her hair and above all her meals? Yet this is the normal condition of the male lover. The female lover has a sharp eye for the set of the neck-tie, the collar must be well laundered, and she much prefers the taste of an ice-cream soda to that of the most profusely moustached lips that were ever pressed to hers.

Females take love in homeopathic doses, males by the bucketful. Thus, Mr. Pell, while in the thralls of the widow Pascoe, neglected his food and his dress. His landlady, Mrs. McPhee, stated to an intimate friend over the back garden wall, that for the whole of the two months he never ate more than would have sufficed for an average man. Mr. Pell's account book, and he was one of those methodical men who entered up every night the expenditure of the day, showed that during the period he had not purchased even one new fancy waistcoat. With a return to normal conditions Mr. Pell found himself suffering from lack of occupation.

Mrs. Pascoe had been occupation enough for him during her brief reign, but with her involuntary abdication, and elevation to the dignity of a grandmother, Mr. Pell felt again within his breast a desire to engage in the stress of the commercial fight. A man with a capital of four figures should have no difficulty in finding a suitable occupation. Yet Mr. Pell was definite that any occupation he entered into must comply with certain conditions.

First, it must not be strenuous or dirty work—speaking in the material sense of the word. Then it must not entail too close attention or too much office routine. Lastly it must mean quick money and plenty of it. The last, like the postscript of a lady's letter, contains the crux of the matter.

Mr. Pell had once in his life engaged in the occupation of Estate and Land Agent. There were reasons that he should not, at least for some time, engage in any of that business. Not that there was anything recorded against him derogatory to his fair name. On the contrary, considered impartially Mr. Pell had been considerably victimised. He had unwittingly possessed a valuable piece of property. Another man had basely deprived him of the fruits of his industry. Mr. Pell did not bear malice and would willingly have shaken Mr. John Joseph Smith warmly by the hand.

For the week succeeding the revelation of the perfidy of the widow, Mr. Pell was the most miserable man on earth—so he thought. He was no longer in love, and he had no occupation. A mind so great as his immediately sought the solution—work!

Mr. Pell was at breakfast. Under the kind administration of Mrs. McPhee he had arrived at the stage of bread and butter crowned with a thick, impenetrable layer of marmalade. Beside him lay the morning post. Mr. Pell never mixed business and pleasure, and the letters lay neglected until the pleasures of the table were exhausted.

At length Mrs. McPhee entered and removed the—er—slain. She smiled as she surveyed the field of battle—Mrs. McPhee was no ordinary landlady, and perhaps she was susceptible to the fine figure of her lodger. Mr. Pell carefully raised his slippered feet on to a chair and reached for his correspondence. The first letter he opened bore the heading of the Great Fallgall Gold Mining Company Ltd., and read as follows:

Dear Sir,

You have no doubt read of

the great success of the mine this Company lately purchased from

you. We believe that you have a sentimental interest in the

success of the property and therefore request the favour of a

call at the earliest possible moment,

Yours

faithfully,

The Great Fallgall G. M. Ltd.

Joseph John

Smith

Managing Director.

Mr. Pell read the letter carefully, twice, and then pondered. What had occurred that J.J. Smith should send for him. Had anything been discovered that might possibly occasion pain and trouble to the late owner, Mr. Peter Pell. He could not think of any point in the transaction he had left unguarded. Finally, neglecting his other correspondence and assuming his hat and boots, Mr. Pell made his way to Landgarten Chambers.

The offices of the Great Fallgall Gold Mine had been removed to a lower floor and accommodation greatly extended. There was every sign of prosperity. A small army of clerks appeared to be busy on the work of recording the amount of gold wrung from the earth. Mr. Pell marched to the shining mahogany counter and rapped impatiently for attention.

At the mention of his name doors flew open by magic and in the shortest possible space of time Mr. Pell found himself face to face with the Managing Director.

Mr. Joseph John Smith was just as gaunt and abrupt as ever. His clothes were perhaps a shade better than when Mr. Pell had first met him but his hands were just as calloused and moist. He greeted Mr. Pell brusquely and pointed to a seat.

"Sit down! Glad you've called. I wanted to see you! Wait until I've got this infernal letter off my mind! Smoke?"

Mr. Pell accepted a cigar and leant back in the client's chair. In days past Mr. Pell had considered himself amongst the elect in the noble art of "Fly-trapping," but now in J.J. Smith he recognised a master mind. Just the right stand off. The busy attitude that was the real thing. It impressed. In fact, it impressed Mr. Pell.

"There, that's done." J.J. Smith swung round to face his visitor. "You're looking all right. How's your health?"

Suitably responding, Mr. Pell made a gentle inquiry as to the meaning of the letter he had received that morning.

"That's all right. Wanted to see you. What are you doing now?"

"Nothing!"

"That's bad. Anything in view?"

"I am looking round for a suitable business to embark my capital in," Mr. Pell explained.

"How much?"

"Somewhere about £2,500," Mr. Pell replied. "Nothing great, to a financier like you."

"Pre-cise-l-y!" drawled J.J. Smith. He placed the tips of his fingers together and gazing into a dark corner of the ceiling. "Perhaps, I can help you." There was a long pause as Mr. Pell decided not to reply.

"Let's be candid," J.J. said suddenly. "You think you are aggrieved by the way we diddled you out of the mine?"

"Not at all," replied Mr. Pell, promptly. "I got my price."

"Rather more I think," exploded J.J. Smith. "I could have had that old hole off you for a damned sight less. I paid you for the booming you did for us."

"I'm satisfied," replied Mr. Pell, doggedly. It was not to his interest, until the other had opened out, to appear otherwise.

"You may be, I'm not," snarled J.J. Smith.

"I'm not going to return you one penny," replied Mr. Pell with heat.

"Who asked you? I didn't!"

J.J. Smith leant over and grasped Mr. Pell's well-turned leg. "There's those with us that think that we could have made use of you and that I was a fool to let you out." Then after a pause he continued. "I'm one of them."

Pell said nothing. For the moment he could not grasp the situation. He was a man offering something for nothing. Somewhere in this wood-pile hid a nigger. It was up to him to scoop out the intruder.

"If you're on for a good thing I have one to offer you. There's your desk—" pointing to a far corner, "—and there's a pile for you to make if you choose."

"And what do you and your friends want from me?" retorted Mr. Pell cautiously.

"We want you to join the Board!"

"That means qualifying," replied Mr. Pell. "I am afraid I can hardly do that!"

"Why not?" J.J. Smith had slipped down in his chair until his head was only a few inches above the backrail. "Why not?"

"I'm not putting any of my cash into gold mines." Mr. Pell winked a knowing eye at Joseph John Smith.

"Bosh," replied that individual impolitely. "Who asked you to do any such thing? That part's already arranged. Say you're on and the stock shall be handed over."

"And the conditions?"

"Lord, man, you're as shy as a two year old." J.J. Smith wriggled up in his chair. "Can't you understand plain Australian? You join the Board. We find the qualifications."

Mr. Pell rose from his chair and bent over J.J. Smith aggressively. "Look here! You may call me a two-year-old, or any other thing that takes your fancy, but I'm not buying a pig-in-the-poke from you or any other man. Where do you and your Board come in?"

"Top hole, sonny!" J.J. Smith wriggled himself to a seated position and laughed into Mr. Pell's face. "Lord, what a suspicious brute you are. Look here! You join the Board. We find the qualification shares. There's your desk. You come and help me work things. Are you on?"

For some moments Mr. Pell considered. As the proposition stood he could see no danger to his pocket. Yet he was to get a lot and the other party's share was in the mist. Was there anything wrong with the mine? Did they want to mix him up in the matter and make a scapegrace of him or was Smith simply out to raid his bank-roll? Either possibility held an attraction that appealed to the vanity of Mr. Pell. The man that could get him into a corner and skin him, monetarily or in reputation, did not in Mr. Pell's opinion live. There was a catch somewhere. Where was it? Mr. Pell determined to find out.

"I'm on!" he announced, briefly.

"Good!" J.J. Smith rose to his feet and extended a large hand for Mr. Pell's grip. "Meeting of the directors this afternoon. Three p.m. You'll be appointed and take your seat at next meeting. Start here tomorrow morning, and I'll make you sweat or my name's not J.J."

During the rest of the day Mr. Pell wandered from one acquaintance to another looking for the "nigger." In every quarter he found the Mine well spoken of. Shares were hard to get and there was every prospect of them being quoted at a premium when a quotation was obtained on the Stock Exchange.

From a friend Mr. Pell obtained a prospectus of the Company and found that the qualification of a Director was one thousand fully paid up pound shares. Why then did Mr. Smith and his fellows want to part with £1,000? There were good names on the list of directors, and Mr. Pell did not flatter himself that his name would lend any further lustre to the Mine. Many plausible suppositions occurred to Mr. Pell, but all were rejected. He was to get too much and give too little—now he was to give nothing.

Nine-thirty the next morning Mr. Pell entered the offices of the Great Fallgall G. M. Ltd., very curious to know what the future held. It was, thought Mr. Pell, something like the old conjuring trick where the operator takes an empty hat and produces from it many interesting things and finally a cannon ball. Mr. Pell shivered at the idea of the cannon ball. If there was a quid pro quo in the present arrangement, then it would most probably assume quite the weight of a cannon ball when it descended on his head. In fact, Mr. Pell took a surreptitious glance at the inside of his hat as he hung it on the peg.

The desk allotted to Mr. Pell was a handsome piece of furniture. Alone in the office he examined the drawers and found bundles of prospectuses, note heads, and envelopes. Nothing suspicious, nothing to give him a clue to what he had come to believe was a carefully baited trap.

Finally he resorted to the morning paper and waited. About ten o'clock J.J. Smith walked in and greeted Mr. Pell boisterously.

"Great man!" he chuckled. "Here as soon as his clerks. Just the man for the company."

Quickly opening the letters he passed a liberal half over to Mr. Pell. "These are yours. See! You're our publicity manager. Interview people, and especially press men. Take that work off me, I can't stand it. Just your line. I'm a mine man."

"I thought you were a sheep man." Mr. Pell could not resist the gibe.

"Good for you!" J.J. was not at all abashed. "I picked up a sheep once or twice and got a liberal portion of his fleece."

Once on the job Mr. Pell thoroughly enjoyed himself. J.J. Smith did not spare him either in the work or in the matter of publicity. He was introduced to the callers as the man who had given Western Australia the inestimable benefit of the Great Fallgall G. M. He was acclaimed as the discoverer. Before he closed his desk for the day he had interviewed half-a-dozen journalists on the finding of the mine and its entirely fictitious presentation to the State. The morning's newspapers promised to be interesting reading.

Mr. Pell waited anxiously for the Board meeting. It was tolerably certain at that table something would be said, or done, that would give him a clue to the peculiar position into which he had been forced by J Smith. But when the Board met, and passed, he was just as wise as ever. Two things he noted for future reference. First that the output of the mine was abnormal, and secondly that the Board bowed very gracefully to the opinions of Smith. The opening of the mine with its tremendous crop of gold bearing ore had constituted a great advertisement but in the newspaper world all events have their allotted span.

When Mr. Pell came back to the Company he found that other interests had taken the place of the 'richest mine in the State' and that the Company was expected to pay for its advertisements at the usual rates. Further that 'puff-pars' were at a discount. The position in which Smith had placed Mr. Pell altered this for some time. There was a new interest in the Mine through the advent of the 'discoverer' on the Board. But the sensation was only short lived and the 'puff-pars' again became hard to get.

"You've got to wake it up, Pell," remarked J.J. Smith one morning. "You've done well so far. Truly a remarkable imagination. You should have been a novelist. But it's dying out. One short paragraph in two days. Won't do, Pell! Won't do!"

"What do you want me to do?" Mr. Pell was annoyed. "I'm not mountebank for the Company. Do you want me to stand on my head?"

>Mr. Pell was annoyed. It was only rarely that he allowed himself to descend from the niceties of speech. In fact he had been heard to comment adversely on the new Australian language that is coming fast to the fore.

"That's your funeral, Pell, my boy," serenely observed J.J. Smith, ignoring the irritation of Mr. Pell.

"Four days and we get our quotation. Get a big sensation to boost the event."

Mr. Pell swung around to his desk and thought hard. Slowly an idea formed in his mind. It would be a big sensation not only to the public in general, but to Mr. J.J. Smith in particular. If he could only work it!

Just before four o'clock Mr. Pell closed his desk and took down his hat.

"Going early," remarked J.J. Smith. "Got that sensation?"

"I have an idea at the back of my mind," replied Mr. Pell quietly. "I think, I am sure, I can promise you a considerable sensation."

"Good man!" Mr. Smith resumed his usual genial manner. "Want any cash?"

"A cheque might be useful."

"How much?"

"A couple of hundred will do."

Mr. Smith scribbled a cheque and passed it over. "Am I to know the details," he enquired.

"Not at present," replied Mr. Pell gravely. "I should prefer it to come as a surprise to you."

"All serene!" Mr. Smith was not curious. "Account for the cash when you are ready."

Mr. Pell paused at the door.

"By-the-bye," he suggested, "what of those shares of mine. The Director's shares you know. I suppose they are my property?"

"Certs, old man. You've earned them. I'll have them sent along to your house." Mr. Pell had thought of dipping his hand into his pocket for the surprise packet and reimbursing himself from the Company's exchequer later. The offer of the cash and shares was too good to be refused. Mr. Pell never ignored the small details. Before returning home Mr. Pell sought out a friend, who had some knowledge of mining. They had a long conversation, at the end of which Mr. Pell felt relieved. His friend also looked happy.

For the next couple of days Mr. Pell avoided the streets and instructed his landlady to inform callers that he was away in the country. Daily he scanned the newspaper and noted the telegrams printed from the mine manager stating the progress made and the number of ounces to the ton the ore was giving.

On the morning of the fourth day he walked into the office of the Company and hung up his hat on the accustomed peg. J.J. Smith was at his desk.

"Back again Pell," he remarked carelessly. "How's the sensation?"

"Complete, Mr. Smith," replied Mr. Pell solemnly. "The mine will be sprung tomorrow." The two gentlemen enjoyed Mr. Pell's joke to the full. Both had a different, yet curiously similar, construction to the double innuendo.

At the luncheon interval Mr. Pell interviewed his broker and in consequence his bank balance suffered exceedingly. Later in the afternoon Mr. Smith announced that he was called out of town and would give full authority to Mr. Pell to act for the Company during his absence. The papers were duly completed and Mr. Smith took his leave, somewhat sardonically congratulating Mr. Pell on his elevation to the honours of Managing Director. He said something about dead men's shoes. Mr. Pell smiled. In due course a Stock Exchange quotation was obtained throughout the Commonwealth and reports began to flow in of the extraordinary popularity of the mine with the investing public. Before the close of the first day the shares were jumping to the skies. The second day fresh reports of enormous finds on the mine were received and published and the shares again responded.

The Advertiser the following morning, published the first news of the greatest swindle in Western Australia. It took the form of a telegram from an investor who was visiting the mine. It was a long telegram, but every word was thrust at the people who had had control of the Company. There was no gold. There never had been any. The experts had been grossly but cleverly deceived. The mine had been salted heavily. The progress telegrams, faked. The whole thing was a fraud from beginning to end.

Mr. Pell did not visit the offices of the Company that day. He remained in the most rigorous retirement. Deluded investors besieged the offices of the Company and the police had to be called to preserve order. Late that afternoon a boy left a letter for Mr. Pell. He stated that a gentleman who had left Fremantle by the Amoora had given it to him with half a sovereign and strict instructions to get it into Mr. Pell's hands that day. It read—

Dear and gullible friend—

I am

off on a little jaunt to the Old World taking with me a rather

large souvenir of my pleasant stay in Western Australia. Give my

love to all at the office and tell them not to expect me

back.

Yours,

Joseph John Smith.

Mr. Pell sent the letter along to the Advertiser, greatly relieved. The tone of the letter was sufficient to fix the blame on the right shoulders.

The downfall of the Great Fallgall G. M. Ltd was great and complete. Many thousands of people lost their savings in the crash. The newspaper gave a well considered opinion of what should be done to Mr. Joseph John Smith, when he was caught. The directors of the company hastened to explain their connection with their late managing director, and the company, endeavouring, with some success, to make black almost like white. And then, like all sensations, the matter passed into oblivion.

A week later Mr. Pell sat in his cosy sitting room with his bank-book on the table before him. He was taking stock of his position.

"One thousand shares at one pound each fully paid up," he murmured, "that being my director's qualification. Brown and he bought two thousand and sold the lot at an average of £5 10s. Say £16,000 all told. Certainly I owe thanks to my sheep friend, Mr. Joseph John."

He lay back in his chair and watched the smoke of his cigar float to the ceiling. "Take from that £500 I gave 'Johnson' for the examination and telegraphing to the Advertiser and allow the £260 Smith gave me for the working of the sensation. Yes! I am quite satisfied."

And then his eyes descended to survey his beautiful new waistcoat, home that day from the tailors. In another part of the town a gentleman of the name of Johnson was boasting of the luck he had had lately. A short trip to the country, first class and all expenses, and a pile in hand on his return.

"Yes," murmured Mr. Pell as he climbed into bed that night. "I don't think I am quite the mug my dear friend Smith thinks," and he laughed, a comfortable self-satisfied laugh, as he arranged himself for the sleep he had so hardly earned.

MR. PETER PELL was not happy and some ill-natured person had suggested in a letter to the Advertiser that he, Mr. Peter Pell, was the criminal brain that had foisted on a too credulous public the Great Fallgall G. M. Limited. The following day the leader writer of the Advertiser took up the story and, without mentioning names, intimated to the Government it would have a short and stormy life if 'someone' was not immediately indicted by the grand Jury, placed in the dock and convicted and sentenced for life, at least. The writer was indefinite as to the charge—any old thing probably—what was wanted was the conviction. The Government, or rather the responsible Minister proved obdurate, perhaps due to the fact that no General Election loomed on the horizon.