a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Death Lands a Cargo Author: Arthur Leo Zagat * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1304631h.html Language: English Date first posted: Aug 2013 Most recent update: Apr 2017 This eBook was produced by Paul Moulder and Roy Glashan. Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html To contact Project Gutenberg of Australia go to http://gutenberg.net.au

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

While the Negro crone muttered, Ruth Adair trembled with the horror of what had happened in her terror-haunted home. Why, then, did she rush, nude and helpless, toward that spot where the phantom ship had landed its grisly crew?

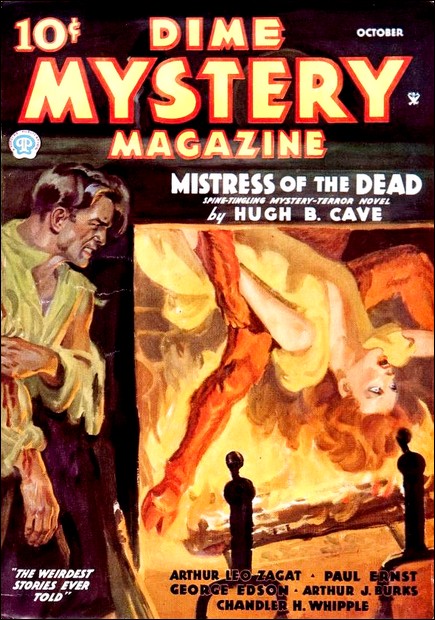

Dime Mystery Magazine, October 1935

THEY had taken away the rude wooden trestles on which the coffin had lain, and the room to which tragedy had called back Ruth Adair was just the same as it had been two years ago when she had left it—except for the heavy, cloying scent of funeral flowers mingling with the salt tang of the sea.

"Jim!" The girl's speech was muted, tight with a queer dread. "Why didn't they let me look at my father before they took him away?"

The driftwood fire within the deep embrasure of the stone-smudged fireplace was shot through with darts of green and scarlet. Shadows overhung the two—dark shadows brooding between the adze-hewn, time-blackened rafters of the low ceiling. Against the firelight Jim Horne's stalwart figure was a tall silhouette, somehow ungainly in the suit of Sunday best he had worn to Cap'n Eli's obsequies. His wind-reddened, broad-planed features were expressionless, masklike.

"You were late." The words boomed from his deep chest. "If we had been any longer, the dark would have caught us out on Dead Man's Arm."

"But it was my father, Jim. My father! I had a right to say good-bye to him."

The man's big fists knotted at his sides. "You had a right to stay here with your father and your old mother and not go off to New York, draining them of their little savings while you studied singing." There was almost savage rebuke in his tone, and bitterness. "If you had stayed here—"

"Jim!" Her sharp cry cut him short. "My life is none of your affair. I told you that—"

"—two years ago, yes. You have not changed." A tiny muscle pulsed in his cheek. "Then I have no business here." He turned abruptly away, was across to the door in three stiff-legged strides. But he twisted around just as he reached it, and there was tortured urgency in his voice. "I came back to say one thing, and I will say it. You must go back. You must go back to the city tonight. You must not stay here."

An old anger flared within the girl. "I must not! Who are you to tell me when to come or go? When I take orders from any man it will not be a slow-minded fisherman, a great hulking clod good for nothing but to heave a net and pull an oar."

Jim's eyes blazed, then suddenly were bleak. "All right," he mumbled thickly. "It'll be your fault..." He pulled the door open—was gone.

Ruth stared at the drab, fitfully lighted oak, and the dull ache beating in her brain was not all because of her loss. Behind her the fire crackled, and slow feet thudded.

"Some tea mak' yoh feel better, Miss Ruth." The corpulent negress coming in from the kitchen had a cup and saucer in her lumpish, black hands. She set them down on the slab-topped chartroom table at which Cap'n Eli would never sit again, conning his maps and sailing in fancy remembered voyages. "Yoh ain't had a mite t'eat sence yoh come home."

"No, Lidy," the girl said drearily. "No, thank you. It would choke me."

"Then stir it. Please, Miss Ruth, stir it for me."

"You're still at that foolishness, Lidy? I..."

"Please." There was an odd insistence in the way her old nurse said it. Ruth shrugged. She was too tired to argue, too dreadfully tired. She swirled a spoon in the streaming liquid, laid it down. The black woman leaned heavily on the table, peering at the circling of leaves on the tea's surface, and she seemed cloaked with an eerie shadow, blacker than the mourning garments in which she was clothed. For a long moment there was no sound save for the dully booming advance of the sea that the ancient walls could not keep out, the surge of the sea coming up close to the house and the swishing hiss of its retreat.

Ruth's finely chiseled nostrils flared a bit, and her chin quivered. "Lidy." Anguish edged the girl's tones, though her eyes were dry. "What was the matter with everyone at the funeral? Why didn't they talk to me or to mother? Why did they run away right after father was—was buried, as though they were afraid of something?"

Afraid! Voicing it, Ruth suddenly knew what the strangeness was that had overlain the heavy-bodied, bony-visaged fisherfolk from the village beyond the dunes. It was fear that lurked in their eyes, some crawling, inexplicable fear that had hurried them along the sandy spit and away as soon as that which had to be done was done, and Cap'n Eli lay couched at the very tip of Dead Man's Arm. Fear had been a tangible presence under the scrub pines that grew only on that narrow peninsula jutting into the water, was inexplicably even now a chill warning in her veins. In God's name what was this aura of fear to which she had returned?

"Lawd a-massy!" Lidy's exclamation jerked Ruth's startled glance to her. "De good Lawd p'eserve us!" It was half prayer, half groan. The woman's work-calloused fingers clutched the table edge and shook with an uncontrollable ague. She was staring into the tea-cup. Grayness filmed her face so that it was like chocolate that has been alternately heated and cooled.

A cold prickle chilled Ruth's spine. "What is it," she cried, momentarily back in her childhood. "What is it you see, Lidy?"

"Ah sees mo' trouble a-comin' to dis house," Lidy chanted in a hushed, rapt monotone. "Ah sees de debbil hisself a-comin' outta de sea." She was looking at Ruth now, and in the black depths of her distended eyes light-worms crawled. "Dis very night—"

Ruth fought herself out of a billowing miasma of unaccountable dread. "Nonsense," she cried. "You can't frighten me with your silly nonsense any more. I'm grown up, Lidy. I'm no longer a little girl."

Protruding, thick lips, a leaden blue, writhed. "No, Miss Ruth. Yoh is no little girl. Yoh is ripe foh Satan an he comin' foh yoh. De leaves say it an' de leaves doan lie. De debbil boat sail on de bosom o' de ocean, an' de fingers o' Dead Man's Arm beckon it. Yoh got to go away. Yoh got to flee right now befoh de moon rise to mak' a path foh de ship f'om Hell. Yoh got to go away."

A queasy dread twisted at the pit of Ruth's stomach. Had Jim's words been a warning then? Was the negress reechoing that warning? "Go away? Lidy, how can I go away and leave my poor mother alone in this lonely house? She is so old, so feeble—"

"How yoh think yoh mother gwine feel when she see yoh wid you pretty haid stomped to bits by de debbil's hoofs like yoh daddy..." The negress' hand flew to her twitching mouth, but Ruth saw only the affrighted, staring eyes, saw only the horror that had leaped to their surface.

"Stamped!" The girl's skin was an icy sheath for her body. "Oh God! That was why the coffin's lid was screwed down so tightly! That was why they wouldn't let me kiss his dead lips! What was it that happened, Lidy? What was it that killed him?"

Lidy's terrified glance crept to the teacup, to the black oblong of the window beyond which the sea surged, came back to Ruth. "De same thing dat killed Otis Blake. De debbil..."

"Shut up, yoh ol' fool!" The hoarse roar from behind pulled Ruth around to the kitchen doorway. "Shut up yoh fool talk o' de debbil." A huge negro filled the aperture, his shoulders touching the jamb on either side. The firelight slid silkily over the brown gleam of his big-muscled arms, over his columnar neck, was quenched by the sleeveless shirt tight over his barrel chest. "I done tol' yoh I done had enough o' dat." In the dimness Lidy's son was a simian brute; half crouched, prognathous jaw outthrust, corrugated black brow receding from bony eye-ridges.

"William! What does she mean?" Ruth gasped the question at him, forcing the sounds past cold fingers that seemed to clutch her throat. "What—How did my father die?"

The negro's gaze shifted to her, his small eyes red-lit with smoldering, bestial hate. Just for an instant, then a veil seemed to drop over them, and there was only an emotionless black face looking at her. "Doan yoh pay mammy no never min', Miss Ruth."

"Answer me!"

"He walk on de breakwater an' de rocks give way. Big stone fall on his haid. He daid w'en Misteh Hohne fin' him." He was mumbling, evasive. Ruth caught herself up. Lidy's wild words, her own grief, were clouding her reason. "Mammy gettin' weak in de haid, cryin' de debbil done it."

The woman whimpered, "Stones doan' kill Mist' Blake. He lie under de pines an' blood pour outta he t'roat dat's tore open by de sea-debbil's claws."

"By de knife he kill hisself wid."

Lidy's voice rose. "Whah de knife? Dey ain' foun' no knife..."

"Hush." Ruth swayed, clutched at a chair-back for support. "Hush, both of you. You'll wake up mother with your wrangling." Weariness dragged at her, was an aching flood torturing her body.

"Get me a candle. I'll talk to you tomorrow."

Would Jim Horne come to her tomorrow, realizing she had not meant her harsh words?

"Yoh heah dat, mammy. Get Miss Ruth her candle an' den come along to de village."

"To the village? You—aren't you sleeping in your room behind the kitchen, Lidy? Aren't you...?"

"De las' year Cap'n Eli mak' me leave de house w'en I get troo my work. He say he doan wan' nobody in de house at night. But I stay here tonight. I sleep in my ol' baid."

"Yoh will not!" William's protest was harsh-voiced. "Yoh'll come home..."

The black woman turned on him, and suddenly her cringing was gone and she was erect, determined. "I sleeps heah, an' I watches ober Miss Ruth. Remembeh dat, Willyum. I watches dat no harm come to huh, like I done watched foh sebenteen year ontell she went to de city." Ruth was aware that the glances of mother and son had tangled, that a silent, meaningful conflict raged between them. And this time it was the man who gave way.

"Yoh suits yohself," he mumbled.

"I want you, Lidy," the girl put in. "I want you to stay here. It's bad enough that father will not be here tonight."

"Good night, den." The negro growled. "Ah's gwine home befoh de moon rises."

Climbing the partition-enclosed stairwell, shadows retreated from the flickering flame of Ruth's candle and formed again behind her. The worn wood treads vibrated vaguely with the beat of the sea as though the old structure itself were shivering at some dim threat. A sense of foreboding brooded about her, a sense of impending evil. In the hallway Ruth stopped at the door of her mother's room, listened. There was no sound from within, no sound at all.

Her cold hand crept to the knob, closed on it. She was afraid—she was almost afraid to open the door. She turned the knob, noiselessly, pushed against the seamed wood to swing it open, slowly, without a sound.

Candlelight filtered into the slant-ceiled, papered room. It painted with luminance a pinched, worn face that was as white as the pillow on which it lay, as white as the hair that was a wraithlike aureole about the wrinkled brow. One thin, almost transparent hand lay curled, flaccid on the coverlet.

Flaccid—there was utterly no movement in that bed. Janet Adair was ghastly still. Dread squeezed Ruth's heart—and then her held breath hissed softly from between her teeth. Her mother had sighed in her sleep, tremulously. The pale lips moved.

"No, Eli. Don't do it." The breathed words were just audible. "Don't betray the sea you love." So low the muttered speech was that the girl was not quite sure she heard. "Not even for Ruth. The sea's vengeance is terrible. It will take us all before it is through."

The girl waited, but the sleeping woman said no more. After awhile Ruth closed the door and stumbled down the hall to her own old room.

RUTH ADAIR came awake with a start. Dread squeezed her heart, lay heavily upon her, more heavily than the coverlet that seemed to stifle her breathing. The voice of the sea beat against stillness. From outside a sharp sound came, and Ruth knew what it was that had awakened her. There was nothing ominous about the sound. It was only the flap of a sail, of a wet sail spilling the wind. Yet somehow the girl was afraid.

The window was a grey oblong, glowing with the luminance that is forerunner of the moon. Ruth stared at it, chill little shivers running through her. Beyond the window was a sandy beach, running down to the breakwater that defied the nibbling of the waves, and beyond that was the sea. It was all as it had been as long as she could remember, she told herself. Just as it had been—there was nothing out there to fear. Nothing. If she looked out of the window she would see nothing but the beach and the sea.

If she looked out! She dared not look out, and yet she knew she must. She could not lie here, cowering with a nameless terror. She could not lie here watching the shadows move across the ceiling as the moon rose, watching the shadows and waiting, waiting with bated breath for the doom that was creeping upon her, to strike—the doom against which Jim Horne had warned her, the evil Lidy had seen in the Sibylline cup. Her bare feet thumped on the floor, and slowly, step by step, she forced her reluctant legs to carry her to the window.

Water swished, rippling against a long keel. A ship was coming into the cove and the moon was rising. The moon...

The sea was a long, oily heave, and to the right it was blotched by a black bar that was Dead Man's Arm. The cape angled, halfway out, like a bent elbow, and its farther end split into five curled fingers of bleached rock that looked for all the world like a beckoning, skeleton hand. A thicket of dwarfed evergreens made a loose, shaggy sleeve for the arm, ended abruptly at the wrist of that bony hand. It was just there Cap'n Eli had asked to be buried...

There was nothing in the little bay before the house. The vast, darkly undulant expanse to the far horizon was utterly empty. A light showed above and beyond the pines, a point of yellow light. Even as Ruth glimpsed it, it grew, became a crescent whose lower edge the pine-tips jagged. A silvery shimmer glinted on the water, became a lane of golden radiance lying on the bay's surface. From the skeleton wrist it made a path of light to the breakwater—to the gap in the breakwater that must be the very spot her father had lain, pulped by falling rocks the sea had loosened.

A path! The moon was making a path... The girl's throat was suddenly dry and her scalp prickled with eerie fear. A shadow was forming, there in the crook of Dead Man's Arm. It darkened the bosom of the sea—was sweeping along the luminous lane with silent swiftness. Ruth gulped. It was only a catspaw of wind, she tried to tell herself, roughening the water. She had seen it a thousand times... Oh God! It was the shadow of a full-rigged schooner sliding over the cove's surface! Clearly, unmistakably, it was the shadow of a ship close-hauled—but there was no ship to cast the shadow. There was only that ominous silhouette darting toward the shore, toward the house, with a grisly soundlessness...

The shadow of the breakwater swallowed it, and it was gone. But somewhere a pulley creaked, and furling canvas slatted. Somewhere a phantom rope screeched, reeving through protesting sheaves. Ruth moved icy hands, thrusting them at nothingness as if to ward off the approach of terror...

A footfall thudded just below.

Fear slowed, then shook Ruth's pulse, so that her heart jerked like a live creature in her breast. The beach was silvery with moonlight, but the glow had not yet reached the house and a murky gloom lay along the stone foundation walls. Within that pall of shadow something moved, a pallid something, wraithlike, without form.

The little hairs at the back of her neck bristled, and her throat contracted in a low whimper.

A voice rang out. "Who dat?" Lidy's voice, challenging, a-thrill with terror. "Who dat climbin' oveh de breakwater?"

Ruth's gaze darted to the retaining wall of piled, loose stone. The blue lunar glow lay clear along its tumbled disorder, and there was nothing there, nothing except a vague shimmer that might have been the quiver of air rising from the sun-heated rock. Nothing. But a hissing whisper came from the sands as though someone moved across it.

"Who dat a-comin?" The black woman surged out into the light, crouched, staring at nothingness. She was a hulking shape at the edge of the shadow, a white cotton nightgown enveloping her rotund form, flapping against her black shins. "Stop! Stop dah!" Lidy's arm lifted and Ruth saw that a carving knife was clenched in her fist. "Yoh cain't have Miss Ruth whilst I lives. Keep back!"

The knife flickered as if Lidy were slashing at some attacker. It stabbed out and down into empty air, but there was a gruesome chunk as if it had plunged into flesh. The negress tugged it back—its polished blade was oddly dull now, swallowing the light—and slashed again. Then, suddenly, the weapon flew from her hand, arced, thudding to the sand, and she was clutching at her throat, was clawing at it. She was being forced backward, was being driven down to her knees—by what? Mother of Mercy! What grisly invisible power was it that had Lidy by the neck, that was overpowering the old servant?

A horrible, choking gurgle came up to Ruth. It was grotesque, unbelievable. The colored woman was alone out there, absolutely alone, and yet she had fought an invisible someone and had been conquered, was swaying on her knees, was battling unseen fingers that squeezed her throat, cutting off breath, life itself.

A scream rasped Ruth's throat. Lidy was down. She was a convulsed hulk, writhing on the sand. Her head twisted around in the spasm of her anguish, and the girl could see her bulging eyes, her contorted face, the tongue protruding from her mouth. Life was being choked from her, and still Ruth could see nothing of her attacker, could see that there was no attacker.

It was over. Lidy Nore was a still, black heap on the sands, an almost naked corpse, flaccid, pitiful. Lidy was dead on the sands, killed by some dread presence from beyond the pale. Was it thus that death had come to Otis Blake? To Cap'n Eli? Death striking unseen out of the moonlight?

Was that death stalking Ruth now? "Yoh is ripe foh Satan an' he comin' foh yoh." The slain woman's warning sounded in her ears, and horror gibbered at her from the moonlight. "Keep back," Lidy had defied the invisible. "Yoh cain't have Miss Ruth whilst I live." And now she no longer lived.

Lidy had given her life to protect her and she could not leave the old woman's body out there for the crabs and the sand-worms. She pulled herself around from the window, padded to the door. She was out in the musty, lightless passage and its murk was alive with a dark malevolence that had infested all the house. Against the pound of terror in her breast, by sheer force of will compelling her strength-drained limbs to function, she forged through the gloom to the staircase, groped for the banister and went down until she was crouched, trembling and weak, against the rough wood of the entrance door.

Through the panel the sound of movement came, of something dragging through the sand, the whispering sound of furtive movement across the hissing sand. Ruth's hand froze on the door knob. Her whole body was rigid, icy in the grip of a crawling nightmare paralysis that was the acme of fear. The phantom killer was outside. He was coming for her.

Why had she not heeded Jim's warnings, and Lidy's? Why had she not fled from this accursed place while yet there was time? She had stayed because of her mother, and now the doom from the sea was coming to finish its work, to slay her and her mother and leave the house an empty, lifeless shell, staring out at the waters from windows through which there would be none left to look.

No! A sudden, desperate courage surged up in her, broke the impalpable thongs by which terror bound her. It was she for whom the invisible presence came—Lidy's vision had warned that—and if it did not enter the house her mother would be safe...

Ruth jerked open the door, lurched out to meet her doom, lurched down high steps to the sand. Then she stopped, tensed for the leap of the killer, for the pounce of the slayer from the sea.

The roar of the tide beat about her, and damp cold of the shore night struck through the sheerness of her nightdress to chill her body. Moonlight lay, a pallid blue film on the sands, mounded over Lidy's contorted corpse like a shimmering, winding sheet. Dead Man's Arm held the ripple of the cove in its crook, and its skeleton fingers lay beckoning under the gibbous moon. Otherwise there was nothing—appallingly nothing. No living thing moved on the deserted beach.

Ruth moaned, got somehow to the dead negress, knelt to her. The sand here was trampled, torn up by Lidy's struggles. But there were only the tracks of the devoted servant, coming from the steps to the place where she had died in futile sacrifice. There were no footprints, no spoor of whatever it was she had challenged and fought, between here and the breakwater. No sign of any other presence. No sign of how death had approached.

Breath hissed from between Ruth's teeth, and the pounding of her heart slowed. The clean, briny redolence of the on-shore wind was blowing the cobwebs from her throbbing brain. Sanity returned, seeping slowly back to her bewildered soul. Smatterings of things she had read came back to her.

Lidy had challenged something invisible, had fought with an apparition unseen, had been slain by it. Impossible. Was there not some reasonable explanation? Might it not be that the woman had been self-hypnotized, driven half-mad perhaps by her adventurings into the occult, her heritage of superstition? That she had imagined the menace approaching from the breakwater, imagined his attack, and fighting a creation of her imagining died through the collapse of a diseased heart? That was it, of course. She had had a weak heart. Ruth remembered her sinking spells, her distress on occasions of excitement or stress. That was it! The girl gasped with relief grasping reality once more.

The negress' hands were still clutched at her throat, as they had been in her final paroxysm. Ruth reached for them, pulled them gently away.

An eerie dread closed in on her once more. Livid across the folds of the brown skin, a puckered weal ran, and tiny drops of blood oozed where a strangling cord had cut deep. Where a noose had cut—but there was no noose! There was no cord—it had vanished like the garroter who had used it. It had vanished—or never been visible.

Ruth stared at the telltale mark while horror crawled her spine. No phantasm of the mind, no weakness of the heart, had killed Lidy. There was the evidence, clear, unmistakable. The woman had been murdered, cruelly murdered, by a thing unseen, invisible. By a horror fashioned of the moonlight and sea-spume, a slayer visible only to his victim in the final, fatal moment...

A footfall thudded behind Ruth, and a shadow fell across her. The bulking shadow of something man-formed, compact of imminent threat, lay on her, and on the dead woman, and on the sand beyond. She felt the appalling loom of that which cast the shadow towering above her. The shadow's arm moved, and something lengthened the silhouetted arm. Something that must be a thick, gnarled club. Terror blazed across the girl's mind like a bolt of lightning.

RUTH cowered, bent over, waiting for the blow to smash down on her, crushing her skull, pounding her into oblivion. It did not come. Time stretched into infinity, and the club did not fall, and the waiting was more dreadful than imminent death. The waiting, and the slow, cold realization that it was not death with which she was threatened. Not death...

Then—what?...

The question pronged white-hot fingers into her brain, twisted her around. Her staring eyes found columnar, spraddled legs, traveled up to a thick torso, to a ridged, outthrust jaw, and baleful, threatening eyes glaring down at her. To Jim Horne's eyes! It was Jim Horne who stood over her, clad again in dungarees. It was Jim Horne's great arm that hung over her, his raised fist clutched about the butt-end of a stout club!

"Jim!" Ruth heard the name, was aware only after a moment that it had come from her own cold lips. "Jim. You."

His mouth twisted across his colorless face, the only life in that grim mask. "You stayed." His voice was a husked growl. "You stayed here—tonight."

Somehow the girl tottered to her feet. She faced him in white-faced silence.

Horne's club dropped slowly, as though some force outside himself had held it aloft, and now was relaxing its grip. Ruth saw that a long shudder was racking his great body, that the stony composure of his countenance was breaking, that his rough-modeled features were working, were tortured as with some obscure, terrific struggle going on within him. His mouth opened, closed...

And suddenly he was shouting at her, "Get in there!" His blunt thumb stabbed at the house. "Get inside, quick, and bolt the door. Don't open it for anyone. Not even for me. Do you understand? Not even for me."

"Jim. Why..."

"Get in there." His club was coming up again, she could see his knuckles whiten with the strength of his clutch on it, could see his biceps swelling. "For God's sake go, before... Go!"

The impact of his voice whirled her around, hurled her willy-nilly to the house door, through it. She slammed the oak leaf shut behind her, rattled a sturdy bolt into its socket. Leaned against the wood, whimpering. The echo of Jim's thick shout was still in her ears. "Go, before..." Before what? What was the emotion, the madness against which he had seemed to fight? Why had his weapon been raised over her? Why had he warned her against himself? Where had he come from, so silently, so mysteriously, out of nothingness?

It was Jim Horne, she remembered William saying, who had found her father's dead body. Found it? That club, the heavy club his hand had clutched, could smash an old man's head so that it might seem that a rock had pulped it... A grisly speculation trailed across the morass of her pulsing mind.

Oh God, what was she thinking? Jim Horne couldn't be a murderer. Not Jim. Not the boy with whom she had played along the beach and out on the water. Not the youth who had taught her to swim, who had given her her first, clumsy kiss...

But might not some alien being have taken possession of him? Some disembodied spirit brought from out of a watery hell by the ghost ship that, itself unseen, had darkened the sea's bosom with its uncanny shadow...

Ruth jumped, whirled around in response to a sudden, sharp sound. Embers of the driftwood fire glowed fitfully on the hearth, light shimmering through them in glimmering waves... A pine knot must have crackled, burst by the dying heat. That was all.

Ruth's mind flew back to Jim. Her spine prickled to the sensation of a gaze upon her, a hostile, inimical gaze. And then fabric slithered against fabric, far back in the room's vagueness. Stone grated, and in the obscurity under the chartroom table something bulked. Its shadow elongated, a hand came out into the light, a taloned yellow hand. It curved, clawed at the rug, tugged. A head appeared, high-cheek-boned, slant-eyed, thin lips curled over a wide-bladed, cruel knife. Even in that frantic moment Ruth rocked to redoubled horror as she saw it was the futile weapon Lidy had wielded...

The Chinese writhed out from under the table in a single lithe movement, was on his feet. His beady eyes went straight to Ruth, he snatched the dagger from his mouth, leaped for her. She screamed, hurled herself away from the door. Her feet struck the first step of the staircase. She fairly threw herself upward, into the weltering, tar-barrel murk to which it rose. Slippered feet thudded on the stairs behind her, and her heart pounded against its caging ribs, pounded as if it would burst through. She reached the upper landing, whirled to the passage.

The silent pursuer was close behind. Ruth snatched for the knob of her mother's door, twisted, flung the door in, slammed it shut behind her, and twisted the key in the lock... Just in time. A body thudded against the wood, the frail portal shook to the impact.

The girl whirled to look for something, anything, to shove against the door to strengthen it against the attack of the saffron specter that had so weirdly appeared to terrify her with a new menace. She saw a dresser, rolled it against the portal. Rolled it! It wouldn't be of much use when the lock was smashed...

The bed! The great four-poster would make a barricade. She turned to it—and froze motionless, aghast.

The bed was empty! There was the imprint of her mother's head on the pillow. The tumbled sheets still held the mold of her old body. But she wasn't there. She wasn't anywhere in the room. She had vanished, as mysteriously, as unaccountably, as Lidy had died; as Jim Horne had come to order Ruth back into the house.

To order her—not to safety, to the clutches of the Chinese, whose knife was scraping now at the wood of the door, slowly, methodically cutting away the fibers that held its lock! The steel point came through, sliced downward. In minutes the thin panel would give way and he would come in.

He would come in—to sink that steel into her quivering flesh. To tear at her with his pointed talons! Terror engulfed Ruth—all the eerie, incredible terror of the dreadful night that had turned the home in which she was born to a pesthouse of mad menace. Her father, her old servant, mysteriously murdered. Her childhood friend, the man who had not been out of her thoughts in all the long months of her absence, metamorphosed into an avatar of strange threat. An impossible, blood-lusting Oriental impossibly materialized into a vacant room, pursuing her with a curious, silent fury. Her aged, feeble mother weirdly vanished, and the scrape, scrape of cutting steel paring away her own last defense. The doom the black seeress had predicted was closing relentlessly in on the helpless girl!

Mind-shattering, livid fear, voiced at her from the obscurity of the moonlit chamber. Fear was a blaze of black fire in her blood, of madness in her brain. Her wide, staring eyes flickered to the bed where her mother had reposed...

Then the dark mantle of her terror dropped away, and cold rage replaced it. She was no longer a soft, civilized maid. She became a primitive woman, fighting for life, for sanity. Fighting for a loved one. She would find out where they had taken her mother. She would make the yellow devil tell. And then she would wrest their captive from his fellows, if she had to go down to Hell itself to find them, if she had to battle every fiend in Hades.

Ruth crossed to the dresser, pulled out a drawer. Her groping hand touched chill metal, came out with a long scissors, the scissors with which her mother had laboriously cut out little dresses for her, long ago. Razor-edged with many sharpenings, its blades were narrow; their ends, where they joined in a point, paper-thin. The girl clutched her weapon, slid around the dresser and crouched against the wall beside it...

A screech of metal against metal sliced through the swirling chaos of her brain. The carved-out door-lock fell to the floor. The panel banged inward, crashed against the dresser. Something thumped against the portal with a meaty thud and the piece of furniture rolled in on its oiled casters. Ruth glimpsed an emaciated body in the widening aperture, a ribbed, jaundiced torso naked to the waist, crisscrossed by curious, raised lines, its back to her, its sharp shoulder against the wood. Then the muscles in her straining thighs exploded like unleashed springs, catapulting her at the intruder, the scissors in her hand flailing, unsheathed claws of the enraged tigress she had become.

The scissors point struck flesh at the base of the Mongol's neck, met gruesome resistance, ripped a jagged gash, came away. The Asiatic whirled, his scrawny arm darting up, slicing his knife down at Ruth. Her fingers caught the bony wrist in mid-air, halted its lethal swoop.

In the same instant she felt her own right wrist clutched. She strained to get free from the steely grip that held her improvised weapon powerless. She tightened her own grasp on the Chinese's arm. The two froze in a ghastly, heaving deadlock, their feet planted on the floor, quivering muscles battling for mastery. Fetid breath gusted in Ruth's face. Almond eyes glittered malevolently at her from deep-sunk sockets. The Mongolian was hairless, and his skin so tightly drawn over the bones of his head that it was a skull that leered at her, a saffron tinted skull.

Ruth could see the gash she had made in the Asiatic's shoulder, and though it was so deep that the bone showed grayish in the slit, no blood flowed from the wound!

No blood flowed, and no sound came from between the greenish, pointed fangs exposed by writhing, fleshless lips. Eerie terror was back, netting Ruth's form with an icy, prickling mesh. Terror clawed at her, more poignant than the excruciating agony tearing her back and the sinews of her legs and arms. Agony pierced her lungs with each labored, hissing breath as the strength of her first mad onslaught seeped away and she bent back, ever back under the increasing, terrible pressure of her ghastly antagonist.

She was beaten! She gave way, suddenly, toppling backward. The Chinese's own straining effort threw him forward, against Ruth, as the resistance against which he fought unexpectedly vanished. A final despairing instinct jerked the girl's knees up as she fell, they pounded into the yellow man's groin. Even then no sound came from him, but his gaunt features twisted with pain, and his grip on Ruth's right wrist relaxed. She twisted it free, drove the point of her scissors into the corded, yellow neck.

The metal sank in, nauseating her with the sliding sough of its stab. Her fingers touched skin that was clammy, cold, and the weight lying on her was suddenly limp. The deathly chill of it was damp against her nearly nude body. Revulsion galvanized her into a last fury of action. She thrust at the flaccid corpse, beat her shaking fists against it, until she had forced it from her. She rolled away from the horrible cadaver, and lay panting, face down on the polished floor. The flooring vibrated beneath her with a monotonous rhythm in time to the long, dull boom of the sea. She lifted and fell on a weltering tide of dark horror.

"Thank you," a toneless voice grated from above. "You saved me the trouble of disposing of this carrion."

Ruth looked up. Water splashed into her face, a drop of water, stinging, and she stared up into a narrow, grey countenance. In a single frantic flash she saw glittering eyes, a hooked nose and pointed chin, a thin-lipped Satanic grin. She saw dark, stringy hair wet pasted like clinging seaweed to a livid brow, and drenched garments tight on an incredibly thin body, tight and shimmering with a ripple of emerald light like moonlight on windless, stagnant water. She saw long nailed, curved fingers, dripping water, reaching down for her.

Realization rocketed through her. This was the Master of Horror, the fiend come up out of the sea to take her to his dread domain. One reaching claw touched her arm, and its touch was a frigid burning, an electric shock that galvanized her body, so that she sprang to her feet.

The apparition laughed gloatingly, came toward her with appalling surety that she could not escape. He was between her and the door. Ruth whirled, her frantic glance found the open window. Death, any clean death, were better than capture by this sinister creature. She catapulted to the opening. The soles of her bare feet felt the sill as she sprang. She flung herself headlong out, and fell toward the silver glimmer of the moonlit sands.

IT seemed to Ruth that the air was viscid, strangely buoyant, that her fall to death on the glistening sand was weirdly slow as a dive sometimes is from a great height. She did not want to die, terror of oblivion suffocated her even as she fell. She was a child of the sea, and in her extremity the lessons the sea had taught her flashed to her aid. She brought knees up, tucked her arms between them and the soft warmth of her body. Made of herself a flaccid bundle dropping down, every muscle relaxed. The impact of her landing pounded breath out of her, half-stunned her; but her limpness, the shock-absorbers she had made of her limbs, took the blow of the landing and no bones were broken.

She toppled sidewise. Her cheek fell against something, cold, clammy. It was the thigh of Lidy's corpse, and a crab scuttled away. Ruth pulled briny air into agonized lungs, jerked her head away from the grisly touch of the cadaver. Brown-skinned flesh hung in strips where already the beach-scavengers had been at their loathly feeding.

Her glance recoiled from gruesomeness, swung to the wall of the house. She saw the somber roughness of the house's stone foundation, the paint-peeled frame of a tiny cellar window. A spectral something moved vaguely across the black square.

The girl twisted over and attempted to rise from the sand. She had to get up and run over the dunes to the left, over the dunes and away from this outpost of hell. If she ran fast enough she could get away, she could get to the village where people were, human beings who would take her in, who would shelter her against the grisly evil that pursued her. Behind her a hinge squealed, and feet thudded on wood of the threshold.

Ruth sprang erect. A swift, terrified backward glance showed the brine-soaked apparition plunging out, the water-devil with the visage of Satan. Her heels dug into the sand. And then, in an instant before her muscles responded to the frenzied command of her brain, a moving something caught her gaze, something moving at the angle where Dead Man's Arm jutted out from the shore. It vanished under the trees clothing the cape, but Ruth knew what she had seen was the bulking form of William Nore, Lidy's son—and over his shoulders had been the thin, white clad figure of her mother.

She leaped into a frantic, staggering run. She twisted, not to the left, where chance of safety lay, but to the right, to the grisly spit whose skeleton hand had beckoned the hell ship from the sea. The cape cloaked with ominous pines into whose gloom the black man had carried her mother.

Sand spurted from under the girl's flying feet, and the thud, thud of the pursuing fiend pounded after her. The dark thicket flashed nearer, nearer, but the sound of the phantom hunter drew up on her. Terror spurred her to incredible speed, terror of the foul thing stalking her, of the fate to which her mother was being borne. Oh God!—What fate was it to which the negro was bearing the aged woman?

The pines were closed ahead, their lightless obscurity opening to swallow her. And then, suddenly Jim Horne came running from behind the house to intercept her, his club upraised. "Ruth!" he called. "Ruth—stop..."

She did not hear the rest; a final, desperate leap had launched her into the blackness of the pine thicket, and as it swallowed her it blotted out the sound of pursuit, of the two grim antagonists who had joined forces for her destruction.

Ruth plunged through underbrush that tore her flesh, that whipped stinging lashes across her face and body. Brambles caught her nightdress, ripped the filmy stuff from her, so that only a few shreds remained to flutter about her flanks, her breasts. She was following the vague sound of a huge body threshing through the thicket ahead; she was fleeing from the servants of evil who hurtled after her.

Once she heard Jim's voice, distance-muffled, shouting: "Ruth! Wait..." Calling to her as if he thought she was still blind to his betrayal, to his oneness with the fiends evolved from the sea and the moon's lifeless beams. Once she heard a scream from far ahead, a thin, quavering scream that could come only from the throat of her mother. Panic swept her at that sound—and was followed by despair. And then there were no more sounds except those she made herself, crashing through the thicket. That, and the unceasing mutter of the ocean, unseen but close now on either hand...

It seemed that she ran forever, fighting the battering of the dark woods that were in league with her enemies; fighting the weariness that tugged at her muscles, the pain that was a garment for her naked body. She was a wild, mad creature hurtling through an unreal, cruel purgatory...

Light glimmered through the tree-trunks before her, a vine caught her ankles. She staggered, the impetus of her headlong flight carrying her out into a clearing. She pitched to her knees. Stayed there, moaning, not feeling pain any longer, feeling nothing but a renewed burst of horror within her as she stared at something that swayed back and forth, penduluming against the yellow round of the full moon, which rode high now in a lowering sky.

It was a body, it was a woman's body, swinging at the end of a rope, and that rope hung down, straight down from the yardarm of a mast. There were other masts, their yards thickened by furled canvas, their rigging a tangle of black meshing the lunar glow. They sprang from a long, low keel; a black keel that slowly rose and fell on the oily heave of an unreal sea. A sea that shimmered greenly like the shimmer of the garments the fiend wore, who was the captain of the schooner from hell at which she gazed.

Ruth Adair's body twitched and a great wave of terror-spawned hysteria suddenly shook it. Abruptly the girl burst into loud, crazed laughter. Her hold on reason slipped, and an illusory clairvoyance seemed now to reveal the sinister plan of her persecutors. They had played with her. They had let her go, not bothering to overtake her. Of course they had let her go, she was going just where they wanted her to go—to the landing place of their ship, of their schooner from Hades. How they must have laughed, watching her struggle through the woods, watching her running. She could laugh with them. It was funny. Oh how funny it was.

And the funniest of all was that they had used the phantom of her mother to lure her on. The phantom of her mother!

Suddenly the girl's mad laughter ceased. They were coming for her now. A splash in the water was followed by a shadow jutting out from the penumbra of the hellship's keel, and a longboat was riding the water, its oars skimming the waves, dipping and skimming again, like a monstrous water-spider scuttling toward her. It was a spider, and she the fly, and there was no escape for her. She no longer wanted to escape. She wanted them to take her aboard the schooner. She wanted to see her body hang from the other end of that yardarm. And then she would take the spokes of the wheel and steer the vessel back to hell. She knew how to steer, Jim Horne had taught her how to steer. She would sing as they sailed, and Jim would be on the bridge too. Jim Horne, Captain Satan's first mate. And then she saw that Jim was standing above her.

"Jim," she said to him. "Jim, I will steer the ship for you." It was not strange that he was here in the clearing, that he was bending down to her, not strange at all. "When we get to hell Satan will wed us." She could say it now that they were both dead. She couldn't say it in life. She could only mouth bitter words at him, words bitter because he would not love her as she had always loved him. "And then because of our love hell will be heaven."

Then a form came up out of a dark rock pile behind Jim. His grey face was furious, and he bounded toward Jim, a rock upraised in his taloned hand. "Jim!" the girl screamed. "Behind you!"

HORNE whirled, grating an oath. The stone flew at him, bounced off his shoulder. His leap carried him yards across the clearing, his fist slapped into Satan's face. There was a squashing sound, and that gaunt visage was splotched with red. Then two forms were locked in a snarling, growling combat, and Ruth was aghast as the madness died within her and she was aware that Jim Horne was fighting for her, had all through the ghastly night been fighting to protect her.

The girl staggered to her feet. Against any human antagonist Jim could hold his own. But was it a human being he was fighting? And even if it were, even if Jim could defeat him, his confederates were coming from the black-hulled schooner, were coming fast in the longboat that skimmed the water under the drive of powerful oars.

Ruth twisted around. The dory was very close, and she could see its occupants, their swinging backs, their white fists tugging at the oar handles. She could see that there were others in the boat who were not rowing, bent forms squatting between the thwarts. Now a hand lifted and she caught the glint of metal on a yellow wrist, could hear the clank of chains.

Oh God! What was this grisly small craft oaring in, who were the chained beings that made its living cargo? The terror of the night closed in again on her. The keel of the rowboat grated on rock, the bow oarsman turned. It was the negro, William Nore!

Ruth whirled again, just in time to see Jim's great arms lift the struggling, writhing, reptilian form of his opponent high in the air, to see Jim pound him crashing down. "Jim," she screamed. "Watch out! The others..."

Jim came around, a scarlet weal across his cheek, his mouth awry. "It's all right, Ruth. It's all right. They're friends."

He was striding toward her, was tearing the straps of his overalls from his shoulders, and stripping the dungarees down. He stopped to pull them off. "Put these on, darling." He tossed them to her.

The girl caught the garment, started toward the curtaining shrubbery. But a cry halted her, a thin, piping cry from the longboat. "Ruth. Ruth. Are you all right?"

She turned. Her mother was standing up, her old arms outstretched. Her mother!—But the woman's form still hung, a ghastly pendulum swinging against the moon.

The blaze from the driftwood fire on the hearth in the living room of the old Adair house reached high between the age-blackened rafters of its low ceiling, driving away the shadows. "Jim," Ruth said. "I can't understand any of it. Did I dream it all?"

Horne turned from the fire, looked moodily at her. "No. It wasn't a dream. I—I hate to explain it, but I suppose I'll have to... Look, Ruth, you didn't realize how little your father really had when you wrote him for more money. He couldn't deny you. And when William Nore came to him with a proposition that they handle live contraband, he said yes, even though it must have gone against his grain."

"Live contraband?"

"Chinese, smuggled into the country to evade the law. Cap'n Eli didn't realize what he was letting himself in for. The men in that trade aren't human, they're fiends. And this particular crew was the worst of the lot.

"The government realized the Chinks were coming in somewhere along this coast. They couldn't send strangers in, and I was appointed an undercover agent, to try and stop it. Otis Blake was selected to help me, and we were thunderstruck when we discovered that the smugglers were landing their living merchandise on Dead Man's Arm.

"It still didn't occur to us that Cap'n Eli was mixed up in the thing, though we did suspect the negro. However, we couldn't make out how they were being taken away from the spit. From out at sea we could see only that they were being taken into the pines, and they weren't there in the morning. Otis volunteered to hide out there, spy on them. The next day he didn't show up—poor fellow, we found his body on the skeleton hand, his throat cut.

"Lidy started a lot of talk about the devil haunting the cape. A lot of damned fools in the village believed her.

"This was last week. I kept snooping around—and found out that a tunnel had been dug from the woods, along behind the breakwater, then into the cellar of this house. I came to Cap'n Eli with my discovery—and he told me he knew all about it, that he was in on the thing. He showed me a trapdoor under the table, that had been arranged for the Chinks to be brought up and out of if the cellar exit out back were being watched.

"Ruth! I couldn't arrest your father. I gave him a chance to get out of it. He promised me that he would tell the gang he was quitting. He did tell them—I imagine that was the reason they bashed his head in with a rock, out there.

"This morning I got word from our operative in Halifax that a shipment was going out, and I knew they would be landed tonight. With your father gone, I didn't hesitate to have a Coast Guard boat sent down here, had it waiting down the coast, hidden in a cove. I tried to warn you..."

"Lidy tried to warn me too. She must have sensed something coming, and she tried to frighten me away with her talk of a hell ship sailing a moon path on the water."

"I've seen that eerie effect myself. When the schooner came in the other side of the point the just rising moon threw its shadow on the cove out here... Well, I was out behind the house, signaling the coast guard launch when I heard Lidy yelling her defiance of the devil—perhaps that was to frighten you some more, drive you away, perhaps her mind had really given way and she believed the story she had herself invented. At any rate, there was a Chinese in the cellar who was left from the last shipment. He hadn't paid his passage and the devils had been torturing him to get even. The window was too small for him to get out, but when he saw Lidy's knife, he wanted it. He unraveled an old net down there, made a noose which he flipped out through it, got it around her neck. He had a long pole by which he fished the knife in, and somehow he managed to get the strangling cord loose and pull that back in too. He started working at the fastenings of the trapdoor—"

"And got through just in time to attack me," said Ruth, shuddering.

"The poor fellow thought you were one of his tormentors, was wild for revenge. In the meantime William Nore, who had never really gone to the village, had looked out and seen his dead mother. He thought that had been done by the smugglers, scuttled up the backstairs to warn you and your mother. You were not in your room. Again he thought the contraband runners were responsible, he went to your mother. Warning her to be silent he carried her out and down the way he had come. I saw him coming out with her, and by that time had gotten a message that the ship was captured but that Grange, the leader of the gang, had dived overboard and gotten away. I thought that perhaps Grange might make for the house, that the safest place was the ship, sent Nore out there... started around to look for you. As I came out from the corner of the house I saw you running, and Grange after you. I threw my club at him, he dodged it, made the woods. Then I lost him in the underbrush... You know the rest."

"Who—who was the woman they hung?"

"Our operative in Halifax. They discovered she was a spy, took her along and killed her when they landed here, just before the coast guard boat came into sight. They were too late to save her."

"Oh, the poor girl!" Ruth blinked away tears.

"Ruth." The new authority was suddenly gone from Jim, he was again gawky, awkward. "Ruth. I—I want to ask you something."

"What is it?" A pulse beat in her wrists, and suddenly she too was very shy.

"You—you said out there—hell would be heaven because of our love. You—didn't mean that—you..." He bogged down.

"I meant that I love you," she said, and then she was in his arms. "Oh my dear, with all my heart and soul." Hot lips were crushed against hers... After awhile she pulled away, smiled tremulously. "This isn't hell, Jim," she whispered. "But that was a good imitation of heaven."

This site is full of FREE ebooks - Project Gutenberg Australia