a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Landlopers Author: John Le Gay Brereton * A Project Gutenberg Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1300671h.html Language: English Date first posted: January 2013 Date most recently updated: January 2013 Produced by Colin Choat Project Gutenberg Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

TO MY FRIEND

R. F. IRVINE

(Author of "Bubbles, His Book.")

I cannot offer you cakes and ale,

But camp-fire bread and a billy of tea—

A loafer's dream and a swagman's tale.

I cannot offer you cakes and ale,

But a johnnie-cake and some post-and-rail

I trust you'll share by the track with me.

I cannot offer you cakes and ale,

But—camp-fire bread and a billy of tea!

J. L. G. B.

|

A FOREWORD.—Of Tramps and Tramping DAY I (12 March).—Of a Fever in the Veins of Knight Wilford DAY II (13 March).—Of The Boy DAY III (15 March).—How Arthur Seaton promised to write a Letter DAY IV (15 March—later).—Of Sabbath Observance, and how Marjorie hardened her Heart DAY V (16 March).—How Wilford set out for Home; and how he and The Boy shed the Husks of Custom NOTHING TO DRINK DAY VI (17 March).—Of a Swagman, and the Liberality of Tramps; the right Enjoyment of a Camp-fire FIAT LUX DAY VII (18 March).—How Wilford bore him as a Lunatic; how the Trav'lers were posed as Rouseabouts; and how they slept on the Foothills of the Mountains REST DAY VIII (19 March).—How the Rain veiled the Mountains; of such is the Kingdom of Heaven; how the Trav'lers looked for a Camp, and found shelter in a Cave ERRANT LOVE DAY IX (20 March).—Of the Wild Beasts of King's Cave; and the Three Men at Hazelbrook; with the sad Tale of the "Clurk" THE BOND OF THOUGHT DAY X (21 March).—Of Colonel Turbot and the Mystery of the Damosel; the Glamour of Wentworth; and how Wilford's World was transfigured A RIME OF THE SHORELESS SEA DAY XI (22 March).—Of the Passage of a River; the Hills of Many Slopes; the Dreariment of the Black Range; and the strange Foresight of Fence-builders and Road-makers DAY XII (23 March).—Of the manifold verbiage of The Boy; the quest of a Breakfast; the Camp in the Devil's Coach-house; and how Wilford had fair tidings of Marjorie MY DEAR DAY XIII (24 March).—How The Boy stooped for Silverlings; and how Wilford heard the Voices of the Creek MOONLIGHT DAY XIV (25 March).—Of MacEwan the Outlaw; the Advent of Beauty and Fashion; and the end of the Adventure of the Silver Coins A WORD OF LOVE DAY XV (26 March).—Of the Glass Cave; and the Slab Hut FRIENDS OF MINE DAY XVI (27 March).—How the Trav'lers inspected a Selection-fence; and how they slept on a Straw Bolster DAY XVII (28 March).—Of the Diggers' Settlement; the Example of Cathay; and the Friendliness of Mr. Dawson DAY XVIII (29 March).—How the Burly Bushman sped the Trav'lers; and how the Dogs raised up false hopes. Of the Caves House at Wombeyan, and the Tableau of Bluebeard's Wife DAY XIX (30 March).—How Wilford and The Boy Addressed them to Bring a Wild Pig to the Pinfold OPEN SPEECH DAY XX (31 March).—Of the Vision of Marjorie; the Descent to the Wollondilly; the Gift of Heaven; a Night in a Log-house LIMITATION DAY XXI (1 April).—Of a Man and a Dog DAY XXII (2 April).—How Wilford took a Short Cut, and saw Brown Eyes; of the Mark of Civilised Life; and Rest under the Willows WE TWO ARE WED DAY XXIII (3 April).—How the apparent Evil Plight of Wilford won him the offer of a Pair of Boots; and how he became a House-painter for the sake of Saint Charity NOCTURNE DAY XXIV (4 April).—Of the Hard Hearts of Picnickers; and the Pleasant Sojourning at Barrengarry C'EST MOI DAY XXV (5 April).—Of the Free Dealing of Bread in Kangaroo Valley; and the Camping by the Ford DAY XXVI (6 April).—How a Fire leaped on the Store-pile; of the Coming to the Sea coast, and the Noise of Many Waters; and how The Boy walked in a Quagmire DAY XXVII (7 April).—Of the Mystery of the Sea; the Cricket's Call to Arms; Mr. O'Keefe, the Friend of the Weary; the Boarding of the Railway Train DAY XXVIII (8 April).—Of the Hunting of the Black Snake; and of the Gift of Ham Sandwiches; and how a Storm chased the Trav'lers from their Camp A ROUNDEL OF NATURE'S EAGERNESS DAY XXIX (9 April).—Of Three Drunken Miners and a Draught of Rum DAY XXX (10 April).—Of a Sleepy Day, and the finding of a Bed BENEATH THE TREES DAY XXXI (11 April).—Of Mad Weather, and how the Trav'lers met the Queen of Solitude DAY XXXII (12 April).—How the Baker's Wife fed the Famishing Wanderers; and how they fared in a Kindly Haven SYMPATHY DAY XXXIII (13 April).—Of the Gladness of Human Contact; CITY CHANNELS; and how Wilford came Home, and heard Marjorie singing AN AFTERWORD.—Of this Book |

If it be fair to take one's

impressions from English books and papers, I am surely justified in

supposing that the average British "tramp" is a despicable loafer

or an abandoned ruffian. The Australian "trav'ler" is on a

different footing. Ragged prowlers do not hide behind Australian

barns and watch for unprotected females to insult or blue-eyed

babes to kidnap. Our girls can usually look after themselves, and

our infants are saleable only at starvation prices. And yet the

country is full of moneyless men who "pad the hoof" from place to

place, and drift backward and forward, always begging, occasionally

stealing, seldom finding rest, and in some cases quite undesirous

of a more settled fortune or a less precarious mode of existence.

These men belong to the vast army of The Unemployed. When a poor

tradesman or labourer is out of work, he must move on or starve on

the spot. He therefore rolls up his "bluey" and starts off, billy

in hand, "on the wallaby track" in search of a job. But countless

others are engaged in the same quest, and jobs are scarce. Some

wanderers are eventually enthralled by the irresistible charm of

nomadic idleness, and are unable to return to a definite and

cabined way of life.

If it be fair to take one's

impressions from English books and papers, I am surely justified in

supposing that the average British "tramp" is a despicable loafer

or an abandoned ruffian. The Australian "trav'ler" is on a

different footing. Ragged prowlers do not hide behind Australian

barns and watch for unprotected females to insult or blue-eyed

babes to kidnap. Our girls can usually look after themselves, and

our infants are saleable only at starvation prices. And yet the

country is full of moneyless men who "pad the hoof" from place to

place, and drift backward and forward, always begging, occasionally

stealing, seldom finding rest, and in some cases quite undesirous

of a more settled fortune or a less precarious mode of existence.

These men belong to the vast army of The Unemployed. When a poor

tradesman or labourer is out of work, he must move on or starve on

the spot. He therefore rolls up his "bluey" and starts off, billy

in hand, "on the wallaby track" in search of a job. But countless

others are engaged in the same quest, and jobs are scarce. Some

wanderers are eventually enthralled by the irresistible charm of

nomadic idleness, and are unable to return to a definite and

cabined way of life.

In the beginning of the

shearing season, the main current sets westward, and the wayfarers

wander from shed to shed on the inland stations. When shearing-time

is over, the tide sets back towards the cities. Travelling in the

"out back" country is full of hardship—"and there is no health in

it," as a vagabond rouseabout once told me. In the dry season,

hardly a drop of water is to be had: in the wet season, the whole

country is a puddle of mud of various consistency. Travelling in

the coastal districts is distinctly pleasant, if the weather be

moderately fine. Personally, I have never tramped on the western

side of the Blue Mountains.

In the beginning of the

shearing season, the main current sets westward, and the wayfarers

wander from shed to shed on the inland stations. When shearing-time

is over, the tide sets back towards the cities. Travelling in the

"out back" country is full of hardship—"and there is no health in

it," as a vagabond rouseabout once told me. In the dry season,

hardly a drop of water is to be had: in the wet season, the whole

country is a puddle of mud of various consistency. Travelling in

the coastal districts is distinctly pleasant, if the weather be

moderately fine. Personally, I have never tramped on the western

side of the Blue Mountains.

The trav'ler usually gets his food by the system which he honours with the title of "bummin'"—in other words, he begs it. He levies his tax upon every homestead, and everywhere he meets with helping hands. Of course, many graceless scamps take advantage of this state of affairs and roam about the country for a living. They are professional trav'lers. They refuse to work, because for them labour is an unnecessary trouble. They camp on the outskirts of a township until they have thoroughly bummed it, and then they set out for pastures new.

When I am out of employment in the summer time, I become a trav'ler. My tactics depend upon the condition of my finances. Sometimes I pay my way; sometimes I am a bummer. Why I love the rough and ready life of comparative hardship, and what comfort I find in the manifold discomfort of "the track," are questions which the reader may answer for himself when he has come to the end of Knight Wilford's narrative.

It must be obvious to the most casual reader—even to the counter-lunch man, who takes his literature in snacks at the bookstalls—that much of the story is founded upon the author's own experiences. Therefore I think well to explain that "The Boy" is not a portrait of any of my friends, though in depicting him I have found it convenient to borrow a few accidental details (of costume, employment and so forth) from one who travelled with me a few years ago. But essentially "The Boy" is himself alone.

J. LE GAY BRERETON

Still at home: still at

work. From the window where I sit, I can see some of the roofs and

spires of the city, above which hangs the dark morning-cloud of

smoke. By road, it is seven miles to Sydney—seven dreary, dusty

miles. Half a mile to the southward of this house is the village of

Gladesville on the hills above that portion of the Harbour which is

mis-named the Parramatta River. And here I sit, pent in by four

walls and faced by an irregular array of books and manuscripts. The

hideous sameness of things! The misery of clock-work regularity!

This limited existence galls me; and the enforced study of Old

English poetry increases my dissatisfaction. Freedom and action

nerve every line of Anglo-Saxon verse. To start reading the ancient

songs is to plunge into the swirl of foaming sea-waves and to feel

the battle frenzy. If I am to stay here, I must read something

soothing and enervating—conservative and Tennysonian. But only one

thing can bring me peace now. The old longing is upon me—the

longing for the open road and its lazy labour. I want to burst

these prison-walls of home and custom; to meet my mates of former

days on the proper footing, and to mingle with them unrestrained

and unrebuked. My fellow-thanes await me. I hear their voices and I

must go. I must lie close to the living earth, encompassed by the

stars. My eyes are dim with longing for the dear blue of hills and

sea and sky. I am eager for a thousand natural pleasures; to dive

down into cool water and gaze up through spaces of dim green or

grey, or mark in clear depths the blending of tints in wave-worn

pebbles and aquatic weeds; to let the branches of trees sweep

across my face and body, causing indescribable thrills of love; to

lie with my back against a hill and watch slow melting clouds, and

see birds gliding down the wind; to sink my face in sweet-scented

grass, and spread my fingers that I may feel the caress of the

elastic blades; to rejoice in the smooth flow of the breeze; to

stand upon the shore and feel the ceaseless pulsing of the Pacific.

I am hungry for communion with these mates of mine. And then the

freedom from restraint, the fetterless uncertainty of vagrant life!

And the darling children by the wayside!—children who laugh shyly

at the incomprehensible tramp who asks such foolish questions. He

asks them merely for the sake of hearing childish tones and looking

into childish eyes. The confidence of these younglings is not won

until they have done the poor trav'ler a favour—filled his billy

with water, perhaps. It is one of the earliest-developed traits of

our nature that we love better those whom we freely serve than

those from whom we receive service. These things need not be

curiously enquired into. Enough for us that they are good. And the

tramp can appreciate everything, and can find enjoyment even in

misfortune. He is not stifled by conventional obligations. He

wanders at large in a perfect atmosphere of love. He is on the

common level; no social lies raise him to a pedestal or depress him

in a cess-pit. He feels his fellowship with Nature. An individual,

he is yet merged in the universe. He recognises his union with the

Divine. He is a god. And the people whom he passes on the road see

only a tramp with fringed breeches and a hat full of holes. They

wonder at his half-curbed bursts of laughter, and possibly suppose

he may be mad. But he is so brimming with exultant joy that he

would like to clasp the hand of every man he meets, and kiss the

lips of every girl...

Still at home: still at

work. From the window where I sit, I can see some of the roofs and

spires of the city, above which hangs the dark morning-cloud of

smoke. By road, it is seven miles to Sydney—seven dreary, dusty

miles. Half a mile to the southward of this house is the village of

Gladesville on the hills above that portion of the Harbour which is

mis-named the Parramatta River. And here I sit, pent in by four

walls and faced by an irregular array of books and manuscripts. The

hideous sameness of things! The misery of clock-work regularity!

This limited existence galls me; and the enforced study of Old

English poetry increases my dissatisfaction. Freedom and action

nerve every line of Anglo-Saxon verse. To start reading the ancient

songs is to plunge into the swirl of foaming sea-waves and to feel

the battle frenzy. If I am to stay here, I must read something

soothing and enervating—conservative and Tennysonian. But only one

thing can bring me peace now. The old longing is upon me—the

longing for the open road and its lazy labour. I want to burst

these prison-walls of home and custom; to meet my mates of former

days on the proper footing, and to mingle with them unrestrained

and unrebuked. My fellow-thanes await me. I hear their voices and I

must go. I must lie close to the living earth, encompassed by the

stars. My eyes are dim with longing for the dear blue of hills and

sea and sky. I am eager for a thousand natural pleasures; to dive

down into cool water and gaze up through spaces of dim green or

grey, or mark in clear depths the blending of tints in wave-worn

pebbles and aquatic weeds; to let the branches of trees sweep

across my face and body, causing indescribable thrills of love; to

lie with my back against a hill and watch slow melting clouds, and

see birds gliding down the wind; to sink my face in sweet-scented

grass, and spread my fingers that I may feel the caress of the

elastic blades; to rejoice in the smooth flow of the breeze; to

stand upon the shore and feel the ceaseless pulsing of the Pacific.

I am hungry for communion with these mates of mine. And then the

freedom from restraint, the fetterless uncertainty of vagrant life!

And the darling children by the wayside!—children who laugh shyly

at the incomprehensible tramp who asks such foolish questions. He

asks them merely for the sake of hearing childish tones and looking

into childish eyes. The confidence of these younglings is not won

until they have done the poor trav'ler a favour—filled his billy

with water, perhaps. It is one of the earliest-developed traits of

our nature that we love better those whom we freely serve than

those from whom we receive service. These things need not be

curiously enquired into. Enough for us that they are good. And the

tramp can appreciate everything, and can find enjoyment even in

misfortune. He is not stifled by conventional obligations. He

wanders at large in a perfect atmosphere of love. He is on the

common level; no social lies raise him to a pedestal or depress him

in a cess-pit. He feels his fellowship with Nature. An individual,

he is yet merged in the universe. He recognises his union with the

Divine. He is a god. And the people whom he passes on the road see

only a tramp with fringed breeches and a hat full of holes. They

wonder at his half-curbed bursts of laughter, and possibly suppose

he may be mad. But he is so brimming with exultant joy that he

would like to clasp the hand of every man he meets, and kiss the

lips of every girl...

And Marjorie? Is the breach permanent this time; or will she forgive me for the gusty violence of my love? To what end does the Life-Spirit set the blood of a man boiling on the flame of passion? I am a law-abiding subject of a Sovran who crumbles your manufactured rules as Time brings to naught the parchment they are written on. I am called a rebel, because I resist all senseless and unnatural tyranny. And Marjorie? The longest way round, as some Scriptural writer says, is the shortest way home. I shall start for your door, my own, by turning my back on it.

The bell! Gods, how I hate this deadly regularity! Curse their punctual habits! But dinner is dinner.

The Boy crossed my track to-day. He is eighteen years of age, but looks several years younger. By trade he is a house-painter. I asked him whether he would swear mateship and shoulder swags with me. He will.

So it is all settled, and we are to start as soon as The Boy has finished his current job. I must borrow some money. Farewell to conventionality and Anglo-Saxon!

Busted be Beowulf, blasted the aetheling.

Blooming well blowed be the bloke under helm!

But whose ear can I bite for a few bob?

Marjorie is still on the snow-clad heights of displeasure. She was at church this morning. I sat in the next pew. She was supernaturally decorous, and concentrated her attention upon the sermon with a Sabbath solemnity unusual in her. For my part, I tried to look like a despairing penitent. With an expression of sorrow and humiliation, I watched the flies dancing a saraband under the chandelier. But she did not once look in my direction. A holiday will do me no harm, but I'll make up lost time when I come home, for she loves me and I know it.

After lunch, I went across to chat with Arthur Seaton. We sat on the edge of the verandah and smoked.

"Seen Marjorie Traill lately?" I said, blowing rings.

"No," he grinned; "but I expect you have."

"No I haven't," I said. "I'm going away for a while, in a day or two—and you know how a fellow's time all gets taken up."

"Where the dickens are you going now?"

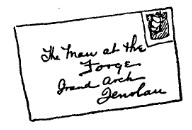

"Don't know. But I wish you'd write to me when I'm away."

"But if I don't know—? "

"Write to Jenolan, and if I don't go there I'll have it forwarded. Let me know about the things you think I take an interest in."

"When will you be back?"

"Don't know. But write in about a week."

"Well, by the Lord, Knight," he said with rather disrespectful admiration, "it's no wonder people say you're mad."

Half an hour later I turned at the gate after saying good-bye, and called: "Arthur By the way, if you happen to see Marjorie before you write, you may as well let me know how she's getting on."

And he nodded and winked. The nod was for me, the wink was for himself.

This morning I met The Boy about ten o'clock. He said he had finished the job on Saturday.

"Very well," I said, "we start to-day."

We gathered together our traps and equipped ourselves for the journey, and by eleven o'clock we were on the road. A trav'ler does not carry more weight than he can help. Bill asked whether he should bring a watch.

"To what end?"

"I don't know."

"Then leave it at home."

I am dressed in clothes which are remarkable only for their antiquity. My brown trousers have an important blue patch, and my shaggy hair protrudes through two holes in my soft felt hat. Into my pocket, along with a tooth brush and other trifles, is thrust a "Canterbury Poets" copy of Leaves of Grass. A large cotton kerchief takes the place of collar and necktie. In my swag I carry two extra flannel shirts and a few pairs of socks, with a piece of American oil-cloth measuring about six feet by four. In the "nose-bag" are small "tucker-bags" of tea, sugar, oatmeal, rice, and lentils, and a tin of mixed pepper and salt. The swag is made by rolling your pair of blankets into cylindrical shape with your extra clothes inside. This bundle is strapped at each end, and the end fastenings are connected by a "shoulder-strap," which in my case is represented by a rolled towel. The swag is slung from the right shoulder. The nose-bag containing food is bound to the upper end of the swag, and hangs in front of the body over the left shoulder. The whole load when properly adjusted is perfectly balanced and easy to carry. The Boy's get-up is similar to mine, the main difference being that his blanket is gaudy with red and blue, whereas mine is an uniform sober grey.

"Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open road," I quoted. And Bill, knowing not The Answerer, nodded and said: "So do I."

We took the main road, and after having lunch in a ferny hollow near the village of Ermington, trudged in dusty content into Parramatta. For about an hour we strolled about the old town which Bill had never before visited, and examined various objects of interest, including the house where a murder had been committed, a dead dog, and the oak-tree against which the wife of an Australian Governor was once thrown from a buggy. A commemorative obelisk stood near the tree, and just beyond the obelisk was a standpipe. We filled our billies—for I was uncertain of the water-supply beyond—and proceeded through the Park in the general direction pursued by the railway line, which we here sighted for the first time. A mile or two beyond the town we pitched our camp in the scrub. Bill was anxious to make a gunyah, though there was absolutely no need for it, and has actually erected a rude and inadequate shelter of gum-suckers. But his energy will abate when the novelty of sleeping in the bush has worn off. A gunyah, by the way, is a lean-to, constructed of boughs or bark, after architectural designs supplied by the blacks. We lit our fire, spread the oilcloth on the ground, and arranged our blankets.

As we sat before the fire and smoked our pipes, after a simple but by no means scanty meal, I remarked to The Boy:—"Bear this in mind, Bill: we have left our forks and serviettes behind us, and we are not to be overshadowed by them. We are free, for a while."

The Boy smoked and grinned, wondering what serviettes might be.

"We are now in the bush, and partners of the wild things. We merely add hypocrisy to their list of virtues."

"Ryebuck!" said The Boy.

"Morality and immorality," I continued in my most pompously sententious manner, "are the twin children of bondage, and we have left them at home with their mother. We are the masters of all wealth. Whatever is good is ours. If birds are caught in an orchard, taking their fill of fruit, they are shot: if we're caught too obviously enjoying our liberty, we shall be immured. There's no difference."

"You're a regular savage," interposed The Boy placidly.

"No," I replied, "unhappily most irregular. God bless all pagan rebels!"

And with that we silently lay back on our blankets and watched through the branches the star-flecked sky.

I write in the midst of a clear silence, shot through with the alternate chirping of frogs and the click and chink of myriads of nocturnal insects. Dear sea of life, I plunge into your warm waves, electrified with the subtle flow of love. I am happy. I am free.

NOTHING TO DRINK

Nothing to drink but water going bad

In hollows where rank grasses rot and stink

Nothing but this foul puddle to be had

Nothing to drink.

The surface of the stuff is green and pink

With iridescent changes; yet I'm glad

To lie out here upon my back and think

For here no longer custom drives me mad;

And in the town, too, I have had to slink

Dry-throated home, and gasp the story sad—

"Nothing to drink!"

|

|

Soon after daybreak, I took the billies down to the creek. The water there was thick and red with mud from the road, eminently suitable for cocoa, but impossible to disguise with tea. However, I followed the stream up, and found a shallow weedy pool, which was not too greatly discoloured. The Boy said it was filthy, but he is not accustomed to the naturally-collected water of districts more than half civilised. On previous tramps I have drunk raw mud which was like thick black cream, and I have made tea which left hard terraces of manure round the interior of my pannikin. I told The Boy so, and he did not believe me. Before he returns home he will learn to style all translucent water clean.

After breakfast we followed the railroad, most of the way through scanty bush, but emerging occasionally upon a road. Near Seven Hills we bought a loaf from a passing baker, and lunched with our feet in the gutter. I was drowsily filling my pipe and watching the intricate dance of a mob of midgets, when a trav'ler swung along the road. He stopped and asked for a match, which I gave him after I had lighted my own pipe with it. Then he dropped his swag, sat on it, puffed awhile, and finally asked:

"From Richmond?"

"No—Parramatta. No regular course."

"Dunno what sorter road this is?"

"No. How is it the way you've come?"

"Goin' to Penrith?"

I blew a ring of smoke and nodded at it.

"Good road," says the tramp, "all the way. You won't run short o' tucker."

"Have a drop o' tea?"

He swigged from the billy, spat out a couple of tea-leaves, and looked at me with meditation in his eye. I yawned a chest-full of smoke at the sky and returned his look, languidly and without interest. He concluded from my appearance that I was sufficiently dishonest to be trustworthy; so he took me into his confidence.

"There's good peaches, a bit back." He jerked his thumb over his shoulder. "I wuz thinkin' at first, there wuz a dog. All right, though. I eat 'em all quick—them I'd got—for fear they'd be found on me."

"Peaches!" The Boy exclaimed, and gulped.

"How far?" I asked; and the good fellow generously gave me full directions. I thanked him, and he heaved his swag to his shoulder, nodded "Good luck!" and went.

It is a remarkable fact that always, when I am on the track, I am the recipient of abundant kindness and hearty hospitality. Most Australians are warm-hearted and open-handed, almost to a fault. Circumstances may obscure their goodness of nature for a time, but in the end the light of their inborn virtue breaks through the clouds, and they live in memory, clad with unselfishness and haloed with loving-kindness. I once camped the night with a shearer, and so far misjudged him that I fell asleep with the idea that he was the stingiest blasphemer on the continent. But in the morning he showed me how to catch stray ducks with a noose of string suspended from a stick.

Dessert is an infrequent luxury to the trav'ler, and we partook of the heaven-sent gift with thankful hearts. We got further supplies of fruit later on, for the orchards abut on the line, and we could not have avoided them without making detours of inconvenient compass.

Our camp to-night is in a coppice of oak saplings, on the flat above a fair-sized creek. I do not know certainly, but I believe the last station we passed was Doonside—a platform with a paddock full of mushrooms beside it. The frogs are chirping and tap-tapping to each other across the creek, and our fire of driftwood is blazing and crackling. The water here is moderately clean, but rather unpleasant in flavour. The Boy insists that there must be a piggery on the bank higher up; but the taste is merely that of rotting foliage. There is a waterhole within a stone's-throw of our bed. In the morning I shall swim.

What a delicious thing the warmth of a fire is! How it soothes the body, and sweeps in soft waves across the skin with every breath of wind! But I protest against stuffy rooms and onion-casings of clothing. Why should our skin be so sensitive to no purpose? Every square inch of body-surface gives foothold to a pleasure. The only way to enjoy a fire thoroughly is to pose before it as a nudity. Perfect pleasure is inconsistent with cerements. Wind, water, sunshine—is it possible for mummy-swathed wretches to realise the ideas represented by these words? If we would understand Nature—sweet naked living Nature; if we would meet her and know her, seeking her not as a blind-worm scientist, but as a lover; if we would be uplifted with the joy of her kisses; then we must strip off these artificial hindrances and become as nude as she. And what is the value of these wrappings, after all? Are they worn as a protection from the cold? But I have noticed that those who lap themselves in the thickest clothing are the first to complain of chilled bones. It is largely a matter of habit. Do clothes add beauty to the human form? Answer, the Art of Greece! But, says a sickly apologist, many of us have bodies which are not joys for ever. And will it improve them, I ask, to smother them in dank and poisonous darkness? Will you attempt to give them beauty by denying them light and air? Ah, but the doctors say—. They have said it was good to swallow doves' dung and powdered unicorn's horn. They say it is beneficial to inject certain excretions of disease. They are always certain. For truth's sake, never heed the doctors. Listen to the voice of Nature, the voice of the Soul, the voice of God. Listen to my voice.

|

FIAT LUX

The light of Love about me glows,

And wheresoe'er it fall,

An inmost core of good it shows,

A golden seed in all.

In mantling shadow did I say

"My heart's a clot of sin,"

Now humbled by the Prince of Day,

I turn my glance within.

|

The morning was very cold, and The Boy declined to have a bath. He said he was afraid of snags. There was a great tree-trunk lying across the hole, and from it I took a dive. When I came out I was cold; so I went out into the open paddock and danced with my shadow on the grass. While I was leaping about, a train rushed past. Somebody waved a handkerchief to me from a carriage window and I responded with my towel. A wagtail swooped about me and chattered of friendship. That was a good time. But The Boy called me from the other side of the creek and cut it short.

"Wilford!"

"Bill Smith."

"Put on your togs, and start."

"Why?"

"Because the people on that train 'll know you're a lunatic, and the police'll be after you from the next station they stop at."

"Oh, air divine and breezes swift of wing! I never thought of that. I'll be ready in a sparkle!"

I went back to the camp, and thrust myself into my scanty raiment in a few minutes. "Ready" I said, and lit up. "Shall we go across the paddocks, or along the line?"

"Along the line. The grass is too wet."

"All right. Quick march!"

"How far is it to Penrith?"

"I don't know, and I don't mean to. I'm content. Why should I worry myself with mathematics?"

"When are we going to have breakfast?"

"I'd forgotten. Next water."

So we halted and boiled oatmeal, and threw water over each other with the billies, and smoked. A meal is always a long ceremony with us. But the police failed to overtake the lunatic.

By the time we reached Penrith, dusk was close upon us, and The Boy was tired. We trudged down the street, in which the electric light had just been turned on, until we met a labourer with a child clinging to each hand. I nodded to him, and he sang out cheerily: "Good ev'n, mate!" We enquired the locality of the usual "camp," and were told it was a dirty old ruin about a quarter of a mile down the road.

"You'd better hurry up, or you won't find room," said the blue-eyed father, "'cause there's about thirty fellers there already, waiting for the Show to-morrow."

"Thanks, mate. Much obliged."

"No trouble. Good night."

We sat on a vacant block of land to consider our course. We got on rather slowly, for I am not used to practical thinking; so I gave Bill threepence and told him to buy a water-melon at the shop opposite. While we ate, a sturdy young tramp came to us from the west. He accepted a laconic invitation by flinging himself upon the grass and hacking a large slice from the melon. He was looking for a camp, and we mentioned the ruin. Incidentally, I remarked that we were going to camp on the other side of the river.

He said: "You'd best look sharp, or it'll be dark first."

I acknowledged the fact. He was kind enough to be interested in our movements, and I followed his lead. It is easy to take the cue from a man like this, and he feels all the better for his exhibition of insight and kindness.

"Goin' out west?"

"Yes."

"Lookin' for work in the sheds?"

"Um."

"D'you know how to shear, then?"

"No."

"Goin' rousin'?"

A nod.

"Bin out before?"

"No."

"My oath! It's yer maiden trip, eh? Well, I'll tell yer where y'oughter go first."

"Wish you would."

"Well, you go ter ——," and he mentioned a gibberish name which I have had no occasion to remember.

"What name?"

"He repeated it, and told me exactly where the station was, and how much I was likely to make. The information was valueless to me, but I was grateful. I set down the incident merely as another example of the readiness of people to help us on our way. In return, I could only tell him that the road before him was a good one; especially on the stage between Parramatta and Sydney. The country within a radius of twenty miles from Sydney is the bummer's happy hunting-ground. More than once, old Murrumbidgee whalers have told me that the Sydney folk are the kindest and most liberal in Australia.

We crossed the Nepean River, after lingering a few minutes to gloat over the long stretch of calm water, beautiful in the evening light with grey and green and rose and yellow and silver. Before us, like a rampart thrown up by giant revolutionists, stood the Blue Mountains, and above them moved a mass of deep purple clouds.

We sleep to-night on the foothills. I had to descend far into a rocky gully for water—sweet, sparkling water—and fell about grotesquely in the dark, to the annoyance of a squealing bandicoot. Meanwhile The Boy lit a fire. When I reappeared, scratched but triumphant, he proposed a gunyah.

"Looks like rain, you know."

"No matter. I hate building gunyahs."

"It means labour, eh?"

"It involves tearing down a lot of young trees."

"That's what I mean."

"Be blowed!"

REST

Rest, for the purple haze the bush bedims,

And, flushed with toil, flung loose along the west,

Day, sighing, feels within his languid limbs

Rest.

His brow by gentle breezes is caressed,

In weary sight the quiet landskip swims,

And silence of all blessings is the best.

With shadow now the gully overbrims;

And Night breathes to his peace-bedrenched breast

—The while her many-twinkling lights she trims—

"Rest."

|

At daybreak rain began to drizzle, but we heaped logs on the fire. As I threw a slab with shaped ends across the blaze, I instinctively looked towards the nearest fence. Then I turned my eyes on Bill, but he whistled to himself softly and busied himself with the tucker-bags. It was a matter of no consequence, for we were not on the road usually taken by trav'lers. We were on the first coach-track, an over-grown disused route. It was not likely that other tramps would suffer for what we did in that wilderness. I asked no questions.

We made a damper and some

porridge. When it was too late, we discovered we were camped within

two or three hundred yards of a patch of pie-melons. It was a pity

but we neither of us cared to take a melon as an outside passenger,

and our vulgar verdict was: Full inside." So we made a start.

Before we regained the main road at Wascoe, we were drenched,

through having to push our way through rain-laden oaks; and every

now and then the grey sky darkened and a sharp shower drifted

across. But we took no heed of discomforts. Why should we?

We made a damper and some

porridge. When it was too late, we discovered we were camped within

two or three hundred yards of a patch of pie-melons. It was a pity

but we neither of us cared to take a melon as an outside passenger,

and our vulgar verdict was: Full inside." So we made a start.

Before we regained the main road at Wascoe, we were drenched,

through having to push our way through rain-laden oaks; and every

now and then the grey sky darkened and a sharp shower drifted

across. But we took no heed of discomforts. Why should we?

We met many trav'lers. Most of them were hurrying towards the Plains, for they wished to try their luck at the Penrith Agricultural Show. They all told us, in one phrase or another, that it was rainy weather, and a good many asked whether it was wet enough for us. The question is humorous in a mysterious way—must be, for each man smiled as he put it.

As we moved on, the showers became more frequent, until rain was the ground material of the weather and dry spells the patches. The roads consisted partly of sticky mud and partly of slush. When we felt hungry, we turned aside for dinner into a gully near Springwood, hoping to find a cave. But there was no cave. We started a fire with some bark and leaves which we found under a log, and then we cooked our dinner. I took off my clothes and spread them near the blaze, where they steamed like a mixen. Meanwhile, every drop of rain touched my bare skin with a tiny ice-cold finger. There is something strangely pleasant in that touch; but my clothes were as wet as ever when I donned them—heavy and clammy—and I was inclined to favour an early camp. The afternoon was well-worn already.

While we were passing a

cottage a little further on—a doctor's house, as I saw by the

brass plate—we noticed two children, a girl and a boy, on the

verandah. Suddenly the little lass hailed me: "Hallo, man!"

While we were passing a

cottage a little further on—a doctor's house, as I saw by the

brass plate—we noticed two children, a girl and a boy, on the

verandah. Suddenly the little lass hailed me: "Hallo, man!"

"Hallo, sweetheart!" I cried back; and meant it. God bless her soul of sunshine!

"How are you getting on? "I asked, assuming old friendship.

"Quite well, thank you," she replied gravely; "how are you?"

"Wet," I said. "Good-bye!"

"Good-bye, man!"

And we saw each other no more.

Is such an incident a trifle? Well, it may be, but the best of life is made of such trifles. I rejoice, and thank the Spirit of Love for them. I have been feeding for hours on the memory of that child's face and voice, and words cannot tell one who does not sympathise how glad I am that the little light-bringer is getting on "quite well."

When one is radiant with love, the children are immediately sensitive of the glow. They are naked to its influence. It is worth the while of philosophers to consider the causes of later slowness of appreciation. The lion will lie down with the lamb when all men understand the eternal Fact which gives their deepest meaning to these lines:—

"Man, a dunce uncouth, Errs in age and youth: Babies know the truth."

We searched gully after gully for a cave, but without success. I found a poor kind of shelter, on private property and well within sight of the proprietor's house. This possible camp was an overhanging rock, close to the ground, and partially sheltered by a rudely-built wall of loose stones. It was a wet and cramp-provoking hole at best. While I was examining it, somebody at the house caught sight of me and shouted warning. So we wandered off through the rain, and The Boy said thoughtfully:

"D'you know, Knight, I don't think I enjoy this tramping quite as much as you do."

Most trav'lers, by the way,

avail themselves of the "boxes" on the railway platforms. I

consider them more cheerless than rain, and you cannot light a fire

in them. Even the intellectual refreshment afforded by quaint

pencil inscriptions on the walls does not atone for the dreariness

of those wretched boxes.

Most trav'lers, by the way,

avail themselves of the "boxes" on the railway platforms. I

consider them more cheerless than rain, and you cannot light a fire

in them. Even the intellectual refreshment afforded by quaint

pencil inscriptions on the walls does not atone for the dreariness

of those wretched boxes.

I slumped along with a light heart, knowing well that—though night was coming rapidly upon us—shelter awaited me somewhere. Truly, "the goddess Wyrd oft withholds misfortune from the man undoomed when his courage sustains him "; and I foresaw a fire and bubbling water. We met a horseman, and asked him whether he knew where we could find a roof to creep under. He looked at us sharply, and said: "I think not; I've had enough of you fellows about my place."

At that I grinned, and said: "All right, boss. You do run into some hard cases and spielers who burn fences and slope with your garden-stuff, and you ain't to blame if you can't see we're not that sort. But don't you know of any cave or old shed about? We ain't particular about sleeping in your pig-sty."

Then he grinned too, but did not soften much. "I'm afraid I can't help you," he said; "but there's a camp of workmen in a cottage about half a mile on. They might find a place for you."

We found the house, and, when I looked in at the warm room, I was glad to notice that it could easily accommodate many more lodgers without inconveniencing the occupants who were lounging about the fire. A hulking black-browed navvy caught sight of me. I nodded, and asked: "Any chance of a camp here, mate?"

He replied: "No, I don't think there is—mate."

"Mate" was an after-thought."

"Any camping-place further on?"

"Dunno."

Another man, who was kicking the blazing logs on the hearth; desisted from his occupation and spoke over his shoulder: "Go to the station—Linden's the name—a piece down the road, an' then foller the line till yer come to a red gate. Go through the gate to the right an' down the track straight ahead of yer. There's a big cave there, they call King's Cave."

"Thanks, mate. So long!" And again the rain received us.

We stumbled along in the dark, found the red gate, followed the track, and there, just over the edge of the hill, was a sandstone cave that might have accommodated fifty men. We were housed at last. The rain got up a demonstration for us on the spot, and came roaring down in a solid mass. A cascade leaped from the hill across the open archway of our home, and the bush was lost in the jaws of the growling storm. We found dry wood, and soon the deeper end of the cavern was faintly illuminated, and we lay on our blankets and swallowed hot pea-soup.

ERRANT LOVE

Fling off the threads that bind

The limbs of Love to-day,

And let him, unconfined,

Go laughing on his way

In bush and street, and bid him greet

All souls by whom his guided feet

Instinctive stray or stay.

And while he speeds along,

Or wanders left or right,

Let certain speech or song

From his warm lips take flight,

Lest, like a bird that flits unheard,

He pass, for lack of spoken word,

Unnoticed in the night.

|

We have not marched many parasangs to-day. In fact, we are only four miles from King's Cave.

It rained all the morning, so we stayed where we were, and watched the occasional shafts of sunshine sweeping over the mountains. There was a little well of clear water in the cave, and, with one drawback, it was a model abode. The floor, dusty and barren as it looked, was the realm of a mighty race of fleas—fierce, tiger-striped little creatures, which would leap in battalions upon your hand and arm as you stooped to gather chips. I was barefoot, and my trousers were rolled to the knee, and upon one of my legs I counted an impi of twenty-eight, which had rushed to the assault as one flea. But they did not annoy us much. A flea is only a nuisance when he persists in exploration.

We bade farewell to the hungry hosts in the afternoon, and walked in pale sunshine to Hazelbrook. Here we bought a loaf of bread, and were directed to another cave. This other cave is much smaller than King's Cave, and is less comfortable, because of huge rocks which lie about the floor. Two whalers were here before us; one, an old cooper, who was sitting on a square block of stone and reading an ancient newspaper with the help of spectacles; the other, a grey-bearded nondescript with bulging eyes. Water dripped briskly from the lip of the cave into a kerosene tin, and lying on one of the discomforting masses of rock were a rusty iron dish and a piece of soap.

The man with bulging eyes told us compassionately that these were "hard times," and asked countless questions concerning our past career and our plans for the future. The old cooper, on the other hand, modestly gave us information about the road before us, and then fell to reading his newspaper again. We were still going west to find work as rouseabouts. We bestowed the lie gratuitously on many a chance-met wayfarer. It is useless to ask why, and it is unnecessary. A simple explanation like that is far more likely than the truth, Heaven knows.

While we were erecting little defences against the incursions of the man with bulging eyes, a young man with a brown beard and a spotless suit of clothes appeared on the scene. He had been bumming the township of Hazelbrook.

"Visitors?" he shouted as he came round the corner.

"Visitors," I nodded.

"Well, I hope they have the spondoolicks," he said, by way of jocular enquiry.

"They'll pay for their lodging next time they're round," I ventured, entering into his mood.

"Always the way," he said, "always the way I'm too soft-hearted for a landlord." And he put down his parcels and laughed at his own humour.

We sat round the fire after tea and diligently smoked. I was reading The Song of the Redwood Tree, when the old cooper interrupted me:

"What's the book, young man?"

"Poetry. Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass."

He nodded, blew a long stream of smoke at the fire, and plunged head-foremost into a string of reminiscences: "I remember a clurk I met at Junee. He was a clever chap with a pen; you wouldn't believe. He told me he was goin' down to Melbourne. He had a son down there, that was a tutor in one o' the colleges—taught, you know, at the University."

"Why didn't his son send him his fare?" asked the brown-bearded man.

"P'raps 'e did," interposed the man with bulging eyes, "'n' th'

ole man drunk it."

"Not him!" said the cooper. "I don't know how it was. Maybe the son was too well orf to notice his father at all. Anyway, we were camped in the bush, an' it come on to rain. He hadn't any tent an' no more had I, an' there wasn't no cave handy, like this. So I says: 'I'm orf!' an' told him to come, too. But not a bit of it! He had some books in his swag, an' he was dead frightened he'd get 'em wet. ' Well,' I says, 'please yourself. There's plenty more books in the world; but ef your binding gets rotted, you'll have to wait till the last day before you can get a new one.' But he only said he musn't wet them books. An he shoved his swag into a holler log, an' sat on top, shiverin'. So I left him an' went to the pub in the town—I don't know if you know Junee?—The Warrigal Inn. It was kept by old Tom Hourigan in those days. Many's the time he's done me a good turn since; but I didn't know him then. I went to the door, an' asked him ef he could give me some kind o' shelter from the rain, an' he took me into the kitchen an' told me to dry meself. Then he says: 'Have you got any money?' 'No,' I says. 'Well, you'd better have a bit of somethin' to eat,' Tom says, an' he got the girl to set out a plate an' a good dinner. After a bit, he looked at me suddenly an' says: 'Ain't you got a mate?' 'Why, yes,' I says, 'I have; but he's sittin' on a log in the bush, because he don't want to wet the books in his swag.' So Tom says he must be a fool, an' any man who didn't have the sense to come an' ask for shelter didn' deserve to get it."

"Quite right!" said the brown-bearded man.

"But pretty soon he turned up, an' I never seen anybody look more miser'ble. He was wet through, an' so was his swag—books an' all. An' his forehead was wrinkled an' the corners of his mouth twitched back, an' the tears were runnin' down his cheeks. But he got a bit better when he had some tucker inside of him, an' Tom made him take off his clothes to get dry, an' lent him a suit of his own."

Here the old cooper sucked vigorously at his pipe, and discovered that it had gone out. He, therefore, took a burning stick from the fire to light it again. He satisfied himself that it was well and truly lit, pressed down the glowing tobacco with his little finger, and, without looking at us, unexpectedly continued his story:—"He had a way of burstin' out cryin' every now an' then. An' the longer he didn't have it, the longer he had it when it come. I remember, when we got down to the border, the man in the punt wouldn't take us across the river. It used to be tuppence to get across then, an' he wouldn't start till we showed him the money; an' of course we hadn' got it. Well,' says this fellow I'm tellin' you about—this clurk—'what ever are we goin' to do now, George?' An' I says: 'Why, there's only one thing to be done. Ef we can't get across in the punt, I suppose we can both swim.' I meant it for a joke, you know, but I'd forgot he hadn' been cryin' for two days. He sat by the side o' the road an' sobbed like a baby, an' the tears came drippin' out between his fingers. It made me a bit angry, so I says: 'What's the matter now?' An' he says: 'I can't do it, George. It ain't no use. I can't swim.' 'All right,' I says, 'I suppose you don't want me to wait here while you learn.' Then he nearly choked himself cryin', an' he got down on his knees, all of a heap, an' he caught hold o' the leg o' my trousers, an' says: 'For Gawd's sake, don't leave me, George!'—like that. An' his hands were shakin' like the water in the top o' that tin. 'Why not?' I says; 'I'm gettin' an old man, an' I can't afford to be wastin' time, waitin' on the edge o' this river.' But he gripped tight hold o' me, an' sings out: 'I can't get on without you, George. Ef you leave me, I'll die before I get to Melbourne.' An' I says to him: 'How did you get on before you met me?' 'I don't know,' he says; Gawd help me, I don't know!' 'Well you must be a baby,' I says; 'you might uv known I was jokin'. Do you think any man in the world could get across just here by swimmin' with a swag an a billy.'"

He paused for so long that we thought we had come to the end of the yarn. But when the brown-bearded man asked: "And how did you get across?" he made a fresh start.

"A chap come along on a horse, an' I says: 'Good day, sir' 'Good day to you,' he says. Can I have a word with you?' 'Oh, yes. What is it?' An' I told him. 'Here's two fellers stopped on their way to Melbourne for the want o' four-pence,' I says, an' one of 'em come all the way from Sydney to see his son at the University.' That was all right. He paid sixpence, an' we all went across together. We got on without any trouble, till we come to Euroa. There was a brewery there, an' I says to the clurk: 'I'm goin' to try an' get a job at my trade here, an' you can wait till I tell you how I get on.' An' he says: 'Well, I hope you don't get any job.' Actually said that, after all I'd done for him. An', mind you, I had to get all his tucker. No bummin' for him. He said he wasn't come so low that he'd beg; so I had to beg for him. An' then he hoped I wouldn' get a job. I never knew a more ungrateful chap. 'Well, I hope I do,' I says, 'an' don't you show yourself at the brewery till I call you, neither; 'cause of you do, we won't be friends—that's all.' An' he kept away all right. I went to the brewery an' saw the boss—Wild, his name was—an' told him what I wanted. 'Well,' he says, 'ef you're a cooper an' not a blanky fool, you're just the man I want;' an' pretty soon we had the affair fixed up. Then I says: 'I s'pose you don't happen to have another job of any kind open? I've got a mate outside that wants to get to Melbourne.' 'No,' he says, 'I don't want any more hands.' 'Then p'raps you'd give me a week's wages in advance,' I says, ''cause he's a helpless sort o chap, an' he ain't got no money.' 'I s'pose he can't figger accounts?' he says. 'Yes, he can. That's just what he can do. He's a clurk.' 'Well, where is he?' I just stepped out to the gate an' whistled, an' waved my hand like that, an the clurk came in. Well, the end of it was that Wild took him down to the cellar an' showed him the door. It was a big door, covered all over with chalk marks—letters an crosses an' curls an' things. You see, Wild couldn't figger or write, so he made them marks on the door, so's he could understand 'em. But he couldn' make up the accounts that way, an' he hadn't anybody to do it for him. We lifted the door orf its hinges an' took it into the office, an' Wild read it to the clurk. But it took him three days to straighten out the accounts. Then, one day, I was workin' in the yard, an out come the clurk, an he says: 'I'll have to be sayin' good-bye, George. The boss has got me a job to take a lot o' sheep all the way to Melbourne.' 'He's a good sort,' I says, for I knew Wild 'ud see the chap was well paid. An' then I says: 'I s'pose he gave you a present, too.' An' he had. He'd given him three quid. So the clurk went orf, an' left me workin' at the job he hoped I wasn't goin' to get. But, before he went, he gave me two o' the books out of his swag, with a bit of writing beautifully put in both of 'em, with curly marks all round." The old cooper indicated lines of writing with his pipe stem, as he slowly repeated the words of the inscription: "From—then he had his name—to Mr.—then he had my name—as a slight but sincere token of his undyin' gratitude for countless acts o' kindness on the road between Junee and Euroa—an' then he had the date. I never knew of he got down to his son all right, but I reckon he did. I wasn't sorry when he was gone. He cried a bit when he left."

"What did you do with the books?" enquired The Boy.

"Oh, I read 'em—they weren't much good—an' then I gave 'em to Mrs. Wild."

The old cooper went on to describe his experiences while he was employed by Mr. Wild. The brown-bearded man retaliated with a tale of his adventures in Dubbo, where he had been grievously swindled by his employer. Then the two swapped lies, until the rest of us were tired out and got between our blankets. As I set down these last words, the old cooper, having vanquished his rival, is spreading his blanket and singing Star of the Evening. All the others are lying on their backs about the cave; and the man with bulging eyes is snoring tremendously. The brown-bearded man folded his clothes carefully, and hung his neatly-indented hat upon his boots. He has no blanket, but has covered himself with a couple of old sacks, and looks like the unidentified corpse of a suicide. The night is cloudy, but no rain is falling.

THE BOND OF THOUGHT

I wonder do you think of me

When I of you am thinking.

With open eyes that hardly see,

I wonder do you think of me;

And now from Love's deep well are we

A draught together drinking?

I wonder—do you think of me

When I of you am thinking?

|

At breakfast the brown-bearded man said:

"You fellows came through Woodford, I suppose."

"We did."

"Did you see the big Government Camp there?"

"'M," I grunted, with my mouth full.

"Any chance of tucker there?"

"Didn't try."

"Oh, they'd give you somethin'," said the old cooper; "they're only poor men."

The sun was shining, and the road was drying rapidly, so we up-saddled early. Near Lawson, we met a family adrift. First of all came a covered waggonette, driven by a stalwart, independent-looking man, beside whom his wife was sitting and suckling an infant. In the back of the vehicle a couple of children were nestling among the blankets. The rear was brought up by a healthy jolly lad on a bare-backed pony. Fair luck go with the party, and happiness sit by their camp-fire! The sight of them was good.

At Wentworth, The Boy proposed that we should have a drink at the Hotel, and in we went. Beer is one of the biggest items on our invisible account-sheet, I am afraid. As we sat with our pints beside us, I remarked: "I've been in this pub before."

"When?" asked Bill.

"One summer, a year or two ago. I was with old Colonel Turbot on a sort of exploring expedition, and we struck the line just here. He's a queer-looking fellow, old Turbot—tall and bony and dark, with little bright eyes, and a tuft of hair coming down to a point on his forehead. Reminds you of a cockatoo. He was a bit tired, so, after he'd swamped his beer, he lay down on a horsehair sofa in the parlour. It was pretty late in the day, and the blinds were down. By-and-bye, a portly old woman came into the room and peered about in the dusk. I suppose she could just make out a figure on the sofa, for she looked that way and said: 'Are you there?' and Turbot said he was. Then she grabbed a chair and brought it over to the sofa, and set it down close to Turbot, and sat on it. The Colonel watched her a bit nervously, because he saw how easy it would be for the lady to make out a case against him. He lay still, and determined not to shift, whatever happened. She leaned forward with her hands on her knees, and said: 'Do you know, I can't make out what's the matter with Sarah!' Turbot, knowing that, whatever Sarah's condition was, he could not be suspected, brightened up at that, and said, with the usual polite affectation of interest: 'No? Really?' 'No,' the old woman said; 'she can't stand.' Turbot thought Sarah was probably drunk, but he only said: 'Well, hadn't you better speak to the proprietor about it?' And, of course, that burst up the show."

"How do you mean?" The Boy asked.

"Why, because she thought he was the proprietor. Drink your beer."

We decided to turn aside from the main road for an hour or two, and to have dinner at the Falls. We went to a store and purchased material for the meal; and the man at the counter thought we were mad, and evidently felt uneasy until we had paid him. We bought a loaf of bread, a pound of onions, a pot of jam, and half a pound of butter. It was a gorgeous meal, and Wentworth Falls never looked better. We sat on the cliffs, and let our gaze rest upon—

"An inland sea of mountains, stretching far In undulating billows, deeply blue, With here and there a gleaming crest of rock, Surging in stillness, fading into space, Seeming more liquid in the distance vague, Transparent melting, till the last faint ridge Blends with clear ether in the azure sky In tender mauve unrealness; the dim line Of mountain profile seeming but a streak Of waving cloud on the horizon's verge."

And the sublimity of the scene was enhanced by delightful dreams of anticipation—fair children, begotten upon the soul by the scent of frying onions.

We did not visit Katoomba Falls, because we did not wish to be benighted on the heights. Instead, we turned off at the Explorer's Tree, and descended Nellie's Glen, a beautiful, rock-walled pass to the Valley. It is in the lower end of the Glen that we are camped. We are under the lee of a sloping rock, close to the creek. The Boy is convinced that we shall be caught by the police and imprisoned during Her Majesty's pleasure for lighting a fire to cook our tea. But Her Majesty may rest in peace. We are very careful, and not a single fern-frond or twig or leaf have we plucked to soften the hard ground beneath our hip-bones. The law has no terrors for me, but I know that every form of sin is an insult to Beauty. To offer Her an undisguised affront is too serious an offence, even for an irresponsible tramp. I dare not defile the very shrine of the goddess, at the moment when her blessing is like sunlight on my spirit. When I feel a pebble grinding between my ribs, I put my hand beneath me and pull the offending fragment out, and murmur: "Oh, blast the!—! I apologise. For Thy sake, most Holy Queen, sweet mistress of my soul!" and I throw the lump of stone into the creek.

I wonder what Marjorie is doing to-night. Within two days, if Arthur keeps his word, I shall have news of her. This life of freedom is a symbolical dream of our love, a shifting pageant of the union of souls and bodies. The bubbling mirth of a creek, the majestic sloth of a sunlit cloud, the ripple of leaves, the interchange of swift glad song by hidden birds, the aromatic scent of certain bush growths in the brushwood—these, and a thousand other appeals to the senses, overwhelm my whole being with subtle suggestion. I am alive, and I love; and the world is a mystical mirror of my inmost self. Why do I thrill with fierce desire at the mere sight of green-fern-fronds unrolling in the sunshine? The Life of the World sweeps through me and over me, and I am a-tingle with passionate sympathy. Even when I lie drowsing by the fire, strong passion couches beside me with strenuous outstretched limbs. And because I have not caged my heart, and taught it parrot-cries of blasphemous commonplace, I am driven out with polite horror and respectable denunciation. If you were here to-night, my true Love, I think I could convince you—if you were here, my Sweet—if you were here.

A RIME OF THE SHORELESS SEA

Sea without shore stretching over and under us;

Knowing too well for exploring and noting

Infinite distances where we are floating,

Knowing that naught can betray us or sunder us,

Swing we, my own,

Borne by the current of passion that carries us,

Sweeps us and pauses, and whirls us and lingers,

Brings us together, attracted, and marries us,

Swirled in the wake of omnipotent fingers,

Always together, and always alone.

|

As we swung gaily across the undulating country which forms the bottom of the Valley, we were greeted at every step with cries of welcome from all kinds of birds. Parrots of various species screamed and chattered, and magpies carolled in the trees. As we were passing a piece of swampy ground, three spur-wing plover ran off, clacking. The kookaburras burst into long peals of laughter. I laughed, too, wildly and plenteously, to the amazement of The Boy, who asked, "What's the joke?" And when I shouted, "Life!" and pointed to a scurrying rabbit, he said he couldn't see anything so funny about it.

We had a little difficulty in crossing Cox's River, which was somewhat swollen. There is no bridge, and the gigantic oaks which have been felled from time to time across the stream have all been swept away. Bill sniffed at the Cox, and called it a dribbling creek, but it took him an hour to get from one side of it to the other, with his swag and his clothes in one big bundle on his head. There are a couple of selectors' huts near the ford, and a half-caste woman strolled down to the river bank to watch us. But she offered us no advice, and I mutely thanked her for her forbearance. She was the last person we saw to-day. There are not many houses near that bridle-track.

As we climbed the deceptive

slopes, after our passage of the Cox, the Boy announced every ten

minutes that he had sighted the top. Each time he discovered his

mistake he began a new search for the summit, and prepared himself

a fresh disappointment. But we did surmount the hill at length and

reached Little River about an hour before sunset. We had a meal,

and discussed the situation. The result was that we started the

arduous ascent of the Black Range at nightfall.

As we climbed the deceptive

slopes, after our passage of the Cox, the Boy announced every ten

minutes that he had sighted the top. Each time he discovered his

mistake he began a new search for the summit, and prepared himself

a fresh disappointment. But we did surmount the hill at length and

reached Little River about an hour before sunset. We had a meal,

and discussed the situation. The result was that we started the

arduous ascent of the Black Range at nightfall.

We toiled up the steep mountain path for about three miles, and then arrived at the saddle where the track turns to the right along the back of the range. We pushed on more rapidly. It was very dark, for the night was cloudy, but we found our way by watching just ahead for the wider glades, and by keeping the foot-worn ground beneath us. If we strayed a yard from the track we could feel grass and dead leaves under our feet. We strode along at the rate of about three miles an hour. We could hear the wallabies scattering before us and thudding through the scrub into the gullies, and once we heard the wail of a bear. Here and there a log lay across the track, and we produced confused crashing and bumping sounds in the gloom, and murmured words of mystic import. It was a weird journey through a desolate land. There was not a drop of water to be found, and we were parched with thirst.

Suddenly the light from a frightened peeping star gleamed in reflection from the ground before me. I grasped The Boy and flung him back, lit a match, and knelt upon the soil. Almost an inch of water had collected in a hole left by a horse's hoof. We drank by turns, lying flat and sucking up mud. A quarter of a mile further on we came to a swamp full of clear pools.

By the time we emerged from the bush upon the Mount Victoria Road, thin veils of mist kept rising from the bottoms and trailing across the ranges, rendering the darkness clammy and ghostly in the drip-starred silence. We turned to the left, and went on until we discovered a grass-hidden creek of running water. There is an old gravel-quarry near the creek—a tiny amphitheatre, where the workers have dug out earth and gravel to bind the loose metal of the road. Here we have pitched our camp. There is abundance of firewood, though there is no shelter from the threatening sky. We are roasting ourselves at a splendid conflagration. Actually, we found a stack of squared logs in this little stronghold. Everywhere we meet the kindness of men and the bounty of the gods.

It rained, during the night, until our blankets were wet. Then the rain gave place to a thick, penetrating fog. We rose before dawn, erected a precarious clothes-horse of dead saplings, and hung up our blankets to dry. Perhaps you think it easy to dry a wet blanket in a fog. There is no difficulty in heating the thing—or even scorching it—but it needs much careful manipulation before it becomes even decently damp. It was a long while before we felt justified in rolling our swags and resuming our march.

Instead of following the main road in all its windings round the mountain-side, we took a track which runs straight along the ridge. A keen wind, which was rapidly blowing the mist away, brought every now and then a slight sweeping shower of fine rain across the ranges. The Boy was full of talk; and every time I had heaped a card-castle of thought, his breath blew it down.

First it was: "My hands are very cold. I don't know if yours are."

Of course he didn't know,

and there was no good reason why he should. The temperature of my

hands could not be a question of pressing interest for him. And, at

all events, his remark called for no reply.

Of course he didn't know,

and there was no good reason why he should. The temperature of my

hands could not be a question of pressing interest for him. And, at

all events, his remark called for no reply.

But he persisted: "I don't know if yours are." He spoke louder, but I retired deeper into my thoughts and was silent.

After a few minutes, he returned to the attack:

"I suppose your hands are pretty cold."

The supposition was a harmless one. I let him suppose.

He nudged me: "ARE THEY?"

"What?" I said wearily.

"Cold."

"Are what cold?"

"Your hands—are they cold?"

"No."

He fell into silence for five minutes. But he was only composing a new catechism.

"We're pretty near Jenolan now."

Blank silence on my part. The statement did not call for contradiction.

"Aren't we?"

"Aren't we what?"

"Near Jenolan."

"Yes."

"Well, I'm hungry. I don't know if you are."

A pause.

"I don't know if you are."

A long pause.

"ARE YOU HUNGRY?"

"Yes; I'd be glad of a bit of bread."

"We may as well have breakfast, then...Don't you think so?"

"No. If we have our usual luck we'll get breakfast this morning without working for it. Don't ask how; you'll see in time."

At nine o'clock we arrived at the settlement of Jenolan, and straightway passed through the lofty natural tunnel which is known as the Grand Arch, and sought the cottage of one of the Cave Guides. A coach-road is being made through the Grand Arch, so that visitors from Mount Victoria may drive through the hill, and into the valley in which the Accommodation House and its accomplices lie like dregs at the bottom of a basin. The whole place is resonant of destruction. The click of hammers and crowbars and the thud of pick-axes are incessant. And at intervals a blast is fired, a shower of slate-blocks rains into the gully, and the roar of the explosion crashes from hill to hill, and rushes, rolling and swaying, through the valleys, till it dies upon the mountain-slopes like a spent wave.

We climbed up the spur to the Guide's house, and I knocked, but nobody came to the door. The worst of it was that I could hear the tinkle of spoons. We went to the back of the house, and a chained dog frantically danced in a semi-circle, yapping and gurgling his regrets at not being able to accord us a warmer welcome. The brute's master heard the noise and came out, with his mouth full of bread and butter. As soon as his tall handsome frame choked the door-way, I bailed him with enthusiasm. His breakfast was not over.

"Hallo, Voss!" I said.

"Hallo, Voss!" I said.

"Hallo, Knight I When did you get here?"

"Just arrived over the mountain. We came to see if you could put us up to a hole in the rock where we could camp."

"Haven't you a tent?"

"No."

"The Coach-house is the best place I know, but they won't let you camp there. I don't know what you're to do."

"Right! We'll look round for ourselves."

"You know your way about, and you're not likely to do any damage. But they're a bit strict about the Arches, so you'd better keep away from them. I'll see you later. I'm having breakfast now."

He nodded and left us. We stared at each other and grinned ruefully. There seemed to be no course open to us except that of cooking our own tucker. But a woman thinks of everything, and Voss is a married man. Before we had turned away, he reappeared and said: "Come inside, and have a cup of tea, Knight." And we went inside and astonished him. When we descended to the Coach-house, we were warm with the glow of inward satisfaction.

The Devil's Coach-house is a huge cavern or arch, through which in flood time runs a creek, violently struggling, tossing tawny arms, and fighting its passage over and between the boulders which block its course. But at present the bed of the creek is dry. The roof of the Coach-house is said to be two hundred and seventy-five feet from the floor. In the walls are innumerable ledges, crevices and caves, and from the roof hang stalactites of pink and green calcite. The wonderful blending of colours in this magnificent hall can only be appreciated after loving study, but the grandeur of its proportions should strike even the most flippant dumb. And in a nook of this home for gods, we made our insignificant camp, like a couple of mice in a cathedral.

Throned on a great block of limestone that must have crashed from the roof many ages ago, I reclined and read Arthur Seaton's letter:

Dear Knight—

Can't make out the lay of the land here. Something seems to be

wrong, but I reckon you know more of that than I do. Last night I

went over to Traills'. Marjorie's cheerful enough, and while I was

there she was so lively she didn't seem able to sit still for five

minutes at a stretch. She'd play a bit, and then slap down the

piano-lid and pick up a book. Then she'd drop the book and run

outside to chuck stones for the dog. And she was ready to laugh at

nothing at all. When I told her I was going to write to you she

said, "Where to?" and before I could answer she said, "Oh, never

mind. I don't want to know!" When I opened my mouth to speak, she

held her hands over her ears and said, "Don't tell me—promise you

won't?" And when I promised she went outside again. Her mother

asked me just afterwards where you'd gone, and I told her as much

as I knew. And there was Miss Marjorie in the doorway, looking

awfully disdainful and careless. By-the-bye, her mother told me the

girl seems put out about something. "But she's been working about

the house, by fits and starts, as though nothing could make her

tired. I can't make her out at all." That's the report, sir. The

old man kept watching her very suspiciously, and he was pretty

short with me. If anything's wrong—anything you didn't make proper

allowance for—I'd advise you to keep out of the way for a bit.

Lassie's pups turned out all right after all—five of them. I'll

keep the best for you. Be good.

A. S.

So Marjorie is restless and excitable; and she wanted hints from which she could construct a likely environment for her dream-portrait of me. The sleepy-looking tatterdemalion who was sprawling to-day on that lump of rock, is an Emperor in disguise, and a man whom the happiest mortal in the world might envy.

In the afternoon we visited the Lucas Cave. I have neither ability nor desire to describe the Caves. Others have tried often enough; and I must refer you to the orthodox guide-books for a thoroughly inadequate and misleading account of them.

MY DEAR

I called you My Dear in a letter,

When you were a free-hearted child,

As blithe as the wind and as wild,

And you flushed with disdain—knowing better—

"His Dear! and since when?" and a stroke of the pen

Stabbed the word by which "Dear" was defiled.

Now strike out the word, I renew it;

In letters provokingly clear

My claim I reiterate here.

But no stroke of pen can undo it—

For the word is a sign that our spirits combine;

You are mine, for you love me, My Dear.

|

We have been through the Imperial Caves to-day, and have seen that they are not bad. Personally I prefer daylight to underground gloom, but all experience is enjoyable, and a procession of idiotic people stooping their shoulders and slipping, with candles in their hands, about a damp chilly passage, is worth seeing. I wonder why they take such delight in tracing resemblances between the wonderful formations of carbonate of lime and such objects as bullocks' tongues, dead fowls, politicians and entrails. And why is there a funny man in every party—a man who with daring originality makes the stupid jokes which the guides have to hear twice a day for ever and ever?

Our money is vanishing too quickly. When we started, we had thirty-five shillings. Now we have only twenty-seven. It must be remarked that we had well-stocked tucker-bags when we left home, and we have no idea how long we are likely to be away. I casually mentioned the state of our funds to The Boy.

"My word!" he said; "we may have to work for our living before we get home."

"God forbid!" I said quietly. And I saw that he was impressed by my simple piety.