a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Cockatoos Author: Miles Franklin * A Project Gutenberg Australia eBook * eBook No.: 0900701h.html Language: English Date first posted: September 2009 Date most recently updated: September 2009 This eBook was produced by: John Bickers Project Gutenberg Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

NOTE The young author wrote this story contemporaneously with the happenings involved and in due course showed it to selected acquaintances. These, sans literary discernment, were dubious about the character of the work. A brave English gentleman, believing in it, showed it to one of London's leading publishers, but he was disgusted by its frankness and said the author should not be encouraged to write. The author, lacking a literary mentor either to confirm or combat such a pronunciamento, thrust the MS. into a box. It lay undisturbed by anything but silverfish for twenty-five years, when I read it. Here are people really young. Time stops still around them for a moment as for figures seen through a stereoscope. They frolic in the spotlight of their own egos in the centre of the floor while their elders are relegated to the side seats. They are surrounded by the idiom of their day and a background of current events and opinions. Caught in the net of adolescence untarnished or unfurbished by Time's perspective they struggle in a maze of inexperience against defeats, hopes, dreams and despairs, normal but so poignant and tragic at their time of life; and, in their case, ambiguous national loyalties are intensified by a double nostalgia. Here was treasure comparable with but superior to a diary. Substitution of names and a refocusing of emphases was all that was needed to fit the story into my chosen scene. —BRENT OF BIN BIN. New South Wales, December-January, 1927-1928.

Larry Healey was ploughing. His horses were hidebound and weak, and the earth was caked like cement. Broken, it took the thirsty winds so that the ploughman moved in a suffocating cloud which filled his ears and nostrils and at times obscured the beasts from sight. Some of that virgin dust did not resettle, but floated high into the air to waste far and wide in the Pacific. For several seasons past the seed had been decoyed above the ground by occasional showers, only to wither before reaching the ear, and Healey had pondered for a fortnight whether it would not be wiser to feed the grain to the starving stock than again to waste it in the earth. The fall of a penny had decided him. He was working in the hope of rain next moon.

On reaching the end of the furrow, where briers high as trees upheld a decrepit brush fence, the horses were given a spell while Healey spat the dust from his mouth, eased his bandless felt hat from his grimy head, and, taking a view of the brilliant sky, wished to God it would rain. Then he jerked the reins—one of rope, one of green hide—and the horses toiled to the opposite headland, bounded by a gaping drain, a grove of dusty wattles and a stud fence. Here he again regarded the relentless arch and wondered where in hell all the rain could be. The theorists who ranted of the security in an agricultural life ought to stand in his old blucher boots! It was grand for those who held fat billets in the Government, with a big screw every month regardless of droughts, floods, or pestilence, to flute of the joys of being on the land. They were having a fine loan of the taxpaying numskulls. All the fat went to the middle-men and officials. Their carpeted offices, padded chairs, and the pleasures of an exciting life were supported by the sweat of the men on the land. Let the town parasites take the plough in the dust, or depend upon livestock for a living in a grassless season, let the grind of it knock understanding into their fat bellies, then hear what they would spout about it!

On all the cockatoo farms of Oswald's Ridges and a hundred adjacent communities were other dusty ploughmen thinking similar thoughts as they scanned the heavens and hoped against hope for rain next moon.

Oswald's Ridges lay between two lesser roads that branched from the Great Southern Road as it left Goulburn, and Healey and his neighbours were members of a community gathered within the radius of attendance at the little public school, with their homes from twelve to twenty miles from Goulburn Post Office. Entrenched families of the district, such as the Oswalds and their cousins the Gilmours, grandsons of abler or more fortunate pioneers, lorded it analogously to the county in England, on which society in the region was sedulously and snobbishly modelled. Their estates, long since mellowed from stations, had been grants to earlier colonists with capital or influence of some kind with officialdom. The only land near to town procurable by the poorer settlers were the gullies and ridges fringing the picked holdings and thrown open to free selection without survey by the land acts of the sixties. In its natural state such country would support little more than a few marsupials or goannas to the acre. Nevertheless, among the selectors some of the hard-headed and thrifty were in the way of becoming squireens or gentleman farmers in relation to the big men, but as yet there were no symptoms of a peasantry firmly rooted in the earth.

The smaller people on the Ridges scratched like cockatoos to rear large families respectably; the fathers and grown sons supplemented meagre farm earnings by shearing or droving or by carting firewood to town. Wood-carting was a poverty-stricken resource which Mrs Healey opposed. "We've fallen low enough without coming to that."

The low rough hills southward ranged up with the miles from Healey's property to a view of Lake George, where all was blue, the water shading into the hills, the hills into the ether in soothing loveliness. From Bungonia to Jingera, from the Tidbinbillas and Coolgarbillies of the Murrumbidgee to the South Coast stretched an area warm and brilliant from prolonged drought, haunting, unique in the blue haze of distance, but acre by acre it was a piteous scene. The droning autumn winds lifted the dust in whorls, the little dam beds were dry and cracked, many water channels empty, paddocks as bare as roads, stock without condition to face the winter. Those animals still able to lift themselves staggered round the waterholes, famished and moaning.

The tree-tops stilled as the sun beat a retreat through the scrub of the gully behind the Healey homestead and a little girl in kip boots splashed with whitewash and with an apron of sacking over her frock came round the corner and began to ascend the track to look for gum on the wattle-trees.

"Now, Freda, don't run away to the scrub when you know it's tea-time."

"I'll be back in a minute, mother."

"Girls much younger than you are are twice as helpful to their mothers."

Rebelling inwardly against this as untrue, the child turned back. She was glad this was not her real mother. As soon as she was old enough she would run away.

The sun, irked by imitating a moon all day in the dust, left his world to the brief twilight as Healey freed his jaded horses. They rolled to relieve their hides, then made towards the creek in whose deep waterholes remained their principal sustenance. Their master straightened himself painfully. He suffered in the chest and shoulder from an old accident, which had left the scar of a horse's hoof on his temple and a more crippling scar on his mind. He was unusually uncomfortable tonight, and hoped this presaged rain. His eyes were inflamed with grit and he rubbed them with horny fingers and beat some of the dust from his patched moleskins as he approached the house with the winkers over his arm.

A family of turkeys settling for the night on the pigsty fence were wrangling loudly about positions. Mrs Healey said it was too dark to do any more to the fowlhouses and came inside to see what progress Lizzie, the servant girl, had made with the evening meal. A family of six gathered round the table—two children, the parents, Lizzy Humphreys, and Ignez Milford. The only conversation was Mrs Healey's altercation with her brood. When he had eaten Healey said he was going to Mazere's for some bluestone. Mrs Healey resented his escape from the house.

"Tell Isabel I can't get over to see her because you are using the horses for ploughing," she complained.

The Mazeres lived three miles away near the road that ran from Goulburn to Kaligda and Gounong. This family, as the Healeys, had come from up the country. Both had fallen to the rating of cockatoos, or farmer-selectors, through inability to keep on the higher ledge of squattocracy. The parents had known each other at Bool Bool, and their families were intertangled in the large clans thereaway. The Mazeres had tried to better themselves by shifting from the back regions of the parental holdings to the neighbourhood of Goulburn, where better opportunities could be expected for the young people. The Healeys had their own reasons, definite and private, for desiring to escape from Bool Bool and their relatives, and, having small capital, had landed on the poor property adjoining Mazere's.

Mesdames Mazere and Healey felt themselves superior. Their meals were accompanied by serviettes and they each had a piano. Mrs Healey was the only woman of her community who kept a girl to help her in the house. Mazere, for a year following his arrival, had driven a pair in his buggy instead of the single-shafter usual among the quasi-farmers. They also gave their houses names whilst most of the other cockatoos were satisfied with the general address of Oswald's Ridges. The Healey place had been known as Blackshaw's deep waterhole till Mrs Healey turned it to Deep Creek. At Mazere's a board on a corner post of a pisé structure roofed with stringybark announced: RICHARD MAZERE. REGISTERED DAIRYMAN. LAGOON VALLEY.

Other boards round about proclaimed similar information, largely legendary; some time had gone by since the smitten region had yielded dairy produce beyond a restricted ration for the homes.

While Mrs Healey was lime-washing her fowlhouse, Blanche, the eldest Mazere girl, was doing the same to the Mazere dairy, and her mother was carrying water from a dam some hundred and fifty yards distant in the effort to save her pot-plants. Allan, the second boy, was feeding a miserable poddy on swill thickened with pollard, and allowed the handle of the bucket to slip over its ears. The calf bolted with a terrified bellow; Allan doubled with laughter to see it collide with a fellow sufferer. As it ran blindly in another direction Mulligan the dog and Billy the pet lamb joined in the chase. Dick, the eldest son, who was chopping wood, dropped his axe and ran after the trio.

As the calf passed Blanche with boys and beasts in pursuit she seized its tail and hung on till she brought it to a standstill.

"Poor little thing, it's a shame to run the flesh off it," she said, as Dick released the shabby trembling creature.

"I assure you it was an accident," minced Allan, who was a budding wag.

"You'll get a lift under the ear that won't be an accident if you give any cheek," retorted Dick.

Mazere, like his neighbour, turned loose a pair of skinny horses and went housewards feeling dirty, uncomfortable, and weary. He had a withered worried face about which the breeze, heavy with soil, scattered his scraggy beard. He was met at the door of the kitchen by his wife's plaints, "Everything is unbearable with dust. My back aches so that I'm sure it's kidney trouble."

"Blanche, why don't you help your mother more?"

"I do everything I can." The over-anxious girl was beginning to regard any joy or relaxation from work as sinful. She established her mother on the sofa, gave her a cup of tea, and then served the family.

Mrs Mazere was difficult to cheer. Her low spirits were attributed to the turn of life, complicated by a weak heart. She dwelt lugubriously on a list of victims of the dangerous age.

"What's this turn of life that women are always croaking about?" inquired Dick.

"Croaking!" wailed his mother.

A glance from his father and a squelching word from Blanche gave the youth to understand that he was guilty of a breach of decency about a feminine mystery comparable to the coming of babies. Every fool knew the facts of that by the time he was ten, but they could be discussed only as indulgence in secret vulgarity by boys and men. Dick walloped around on tiptoe and punched Allan to relieve his resentment of such humbug.

Relief was general when later Healey at the open door announced, "Good evening! Any hope of rain?" Larry was generally a cheery sight when away from his wife.

Mrs Mazere revived. "Come and have something to eat. Is Dot well?"

"I just rose from the table, thanks. Dot's complaining of pains in her back, but I'm afraid they won't bring rain."

The men found comfort in discussing their situation together. Fodder was unprocurable, even at prohibitive prices, and winter approached. The winter of the Southern Tablelands was bleak with many weeks of nipping frost, sleet and wide wild winds that could take the last ounce of flesh off stock and find their way through the possum rugs on the beds.

At ten o'clock the visitor procured bluestone, debated quantities per bushel, and prepared to depart. Mrs Mazere sent an invitation to the Healey family to stay for tea on Sunday after church. The neighbourhood was to muster two days later to intercede with the Almighty for rain. The little wooden church with its toy porch, set in the scrub beside Mazere's wheat paddock, belonged to the Wesleyans but was attended by all Protestant denominations every Sunday afternoon. Mazere accompanied his neighbour as far as the stable and they lingered outside searching the sky for signs of rain and having a last masculine word. Healey, though several varieties of fool in his own estimation and many more in his wife's, nevertheless considered prayers for rain as too foolish altogether.

"It's not praying we want, it's practice. If all the parsons and priests prayed for seven years they couldn't so much as raise one grasshopper one inch from the ground without practical measures."

"Some reckon we're being punished for our sins."

"So we are, the sins of ignorance. We need men to study the natural geographical and climatic conditions of the country and then follow methods of fodder and water conservation in the rolling seasons to tide over the droughts. You can take it from me, there's no use in mumbling prayers."

"The fat would be in the fire if you said so. It makes a bit of an outing for the women, and church is a good thing to keep the youngsters out of mischief."

"It would be more Christian to let the horses spell for the day, but it'll be all the same in a hundred years."

"Yes," agreed Mazere. "What is to be, will be. See you on Sunday."

Oswald's Ridges was indebted to Ignez Milford for adding spice to the daily round. Her lively and unconventional ideas caused commotion among tamer fowl. She had taken it into her head to have a musical career and her parents had weakened to let her come as far as Goulburn to study. This was feasible because the Milfords also had connections in the up-country clans, and for safety Ignez had been deposited with the Mazeres and Healeys. She parcelled her time between the houses to obviate any jealousy and to divide the wear and tear of her presence. When Mrs Mazere was given to headaches and the piano annoyed her Ignez went to Mrs Healey. When Mrs Healey suffered from nerves Ignez returned to Lagoon Valley.

Mrs Healey was to give Ignez piano lessons. Ignez was confident that she could study the theory of music herself from textbooks. Mrs Healey was devoid of musical gifts, but, as prescribed for girls of good family, she had been taught the piano. She was skilful and efficient in anything to which she turned her hands, and had learnt to execute the scales and Czerny and the conventional repertory of drawing-room "pieces", including a Chopin waltz or two and more popular favourites, without a wrong note and in unimpeachable time. She sat beside Ignez for some weeks, but Ignez speedily discovered that her teacher had not the musical knowledge to see or even the ear to know when her pupil was playing other works than those placed on the piano rack. As a beginning, and entirely by her own study, Ignez gained ninety-nine marks out of a possible hundred in the examination in the theory of music set by representatives of the London College of Music. Ignez was hailed as a prodigy and on the strength of it agitated for a more advanced teacher. Mrs Healey took this as an insult rooted in Ignez's conceit and became hostile to the girl's ambition. The two foremost teachers in Goulburn each charged two guineas a quarter. This was considered waste of money by the Milfords, who were unlettered musically, but they compromised upon a woman at one and a half guineas, and Ignez rode to town like the wind once a week with her music roll strapped to her saddle dees. An escort was unnecessary because, as Ignez's father pointed out, she could ride like a horsebreaker, and as long as she rode her own mare nothing on the roads could overtake her. The Milford brothers of Jinninjinninbong bred horses for Indian remounts and there was good imported blood in their walers.

The only dangers to which Ignez was open in her attempted musical training were artistic. These were so grave that she was foredoomed to defeat, but she and those around her were all so abysmally innocent of what any muse demands of those who would follow her that tragedy did not yet cast its shadow. Now sixteen, the girl had a singing voice of extraordinary depth and resonance that filled her adolescent head with dreams. Dick and Allan Mazere and their mates teased her as a bullfrog, but those of musical pretensions were emphatic that she had a remarkable organ. There was the opinion of old Salvatore Tartaglio, a fossicker for gold in a deep wild gully of Jinninjinninbong. When he had come to the homestead for rations, if it also happened that someone had treated him to alcohol or that he had procured a bottle or two of Italian wine, he would demand access to the piano. The vitals of the instrument would be exposed to view and given such exercise as they had not known, and sometimes, if not too hoarse, Salvatore would sing. He would deafen his listeners with operatic arias delivered in the open-throated Italian bellow with more fortissimo than the piano or pianissimo now beyond his ruined organ. There was a legend that he was a stranded opera singer who had contracted the gold fever that had raged in the early nineties on the western goldfields.

He was lavish in encomiums of Ignez and her voice. Santa Maria! What a natural voice! If he could have the training of it! The divine Malibran, Trebelli! All the notes of me, Salvatore, all the notes of Patti, but the voice is cut in two. He, Salvatore, alone could weld that division and make the voice into one tremendous organ. When he was elevated he would rave and weep till the men would calm him by making him helplessly drunk and then take him away to a bunk in the men's hut. He was so unkempt, so dirty, so wild in his uncontrolled emotion, that his bedraggled and depreciated foreign culture could not become evident to the inexperienced circle of Jinninjinninbong, with its conventional and limited codes of gentility.

He would rage that he must take Ignez away with him to save her from the surrounding barbarism, and teach her and bring her out in Paris, in Vienna and Milan. Ach, Santissima! He would show them that Salvatore, the great, the incomparable Salvatore, could return in this new triumph through such a pupil. There would be wild nights. Salvatore would later be deflated, sick, remorseful, morose, threatening self-destruction. He would creep away to hide his shame in the lonely gullies, the cause of his plight, whatever its nature, locked within his breast. His extravagant eulogies were put down to drunkenness, his temperamental aberrations partly to madness or simply to foreignness, peculiarities almost synonymous to untravelled provincials the world around.

As Ignez excited him unduly it was thought wiser to send her to a neighbouring run on some errand when Salvatore was due to appear. Old men often went dotty about young girls, and Salvatore, both drunken and foreign, might be dangerous.

Ignez secretly hugged Salvatore's pronouncements. His praise was intoxicating, and as an accompanist he seemed possessed of magic that could help her with her voice in the middle. He taught her to sing "Ombra Mai Fu" translated to fit her big fledgling divided voice. O santissima, Maria!

Yes, some day she would sing to others—clever, well-dressed, notable people—whose response would be similar to Salvatore's. For the present the church service to ask God for rain was at hand, at which to her own accompaniment on the few live notes of the tiny moth-eaten organ in the little church in the scrub she was to sing "O Rest in the Lord".

In addition to musical gifts, Ignez was an avid reader and took a precocious interest in politics. She despised the usual small talk of women so that they censured her as unsexed, though they revelled in her outbursts.

"I hope you're going to vote for woman's suffrage at the next election," she observed on Sunday evening at tea after church at Lagoon Valley. She had been reading of the work of Lady Windeyer and Miss Rose Scott and ardently espoused their platform. "Mr Mazere, Mr Healey, and Mr Masters, that makes three votes."

Arthur Masters was attributed to Blanche, who hastened to observe, "I think it would be horrible for women to vote. It would make them like men."

"That would be horrible indeed!" Arthur grinned, and Blanche laughed, well pleased.

"Tosh!" exploded Ignez. "Men think women are too weak to study politics, but even in the most hampering states of maternity they are not too weak to feed pigs and rear poddies. When it is wet they paddle knee-deep in cowyards—in silly long skirts, too."

"It would be a grand sight at present to see a few of them in boggy cowyards," chuckled Healey.

"Ghost, yes!" agreed Mazere.

"Ignez, you should not speak so," admonished Mrs Healey.

"But it's quite true. This talk about some things and not others making women masculine is idiotic."

"It would give you the pip," admitted Arthur Masters. "It would be far easier for a woman to vote than to barge around a cowyard." The Masters dairy was a model for the district. A woman never worked in it. Arthur's pronouncement disappointed Blanche. Her views had been tempered for his approval, but he was watching the animated face of Ignez.

"It's like riding," pursued Ignez. "Girls can ride as well as men, even got up in silly binding skirts and other handicaps that would drive men dilly. I've a good mind to ride astride."

"It would be much safer," conceded Healey.

"But it would look so unladylike," insisted Blanche, again failing to win the commendation she craved.

"As to women voting," observed Mazere, "what good would it do when there's nothing to vote for but a useless lot of old windbags?"

"It's the principle of the thing—being classed with children and lunatics."

"You can have my vote, Miss Milford," said Masters. "I'll cast it any way you like if that will satisfy you."

"That wouldn't alter the principle of the thing."

After tea Ignez repeated "O Rest in the Lord". Dick and Masters listened entranced, more with the singer than the singing, which Blanche thought too loud and unrefined. Mrs Healey then played hymns. Ignez found the pitch of these discommoding, and as secular music was forbidden on Sunday, discussion was resumed with the girl as its centre. Mrs Mazere tried to retail her ailments but the zest of the general talk defeated her.

Young Dick was determined to drive Ignez to Goulburn one day soon to seek information regarding the turn of life and other mysteries. He felt that Ignez would be free from the nastiness and pretence of the other girls, which made him feel silly or unclean. He was envious of Arthur Masters, who would escort Ignez home by way of Deep Creek since she was on horseback and all the Healey family would be in the buggy with its rattling tyres and its crying need of a coat of paint. He got ahead of Masters in tossing Ignez to her saddle, which she reached with the lightest touch to her toe.

March and April passed to May, and a couple of days of light drizzle laid the dust. The Healeys were taking advantage of the change to clear up their premises. Ignez wielded a broom of messmate boughs while Mrs Healey sprayed her fowlhouses with a vermin-killer.

In the hope that the coming moon would bring rain Healey had been ploughing for barley fodder. Once more he freed the bony horses and came towards the house, the cold west wind flapping his patched waistcoat and penetrating his thrummy moles. An agony of irritation and a sense of helplessness crushed him.

"God!" he muttered. "A failure! Fifty years more to be corked and bottled in these wallaby gardens!" Old Sool'em ran to meet him, but his master with a rough boot sent him yelping.

"I can see what's coming," said Mrs Healey to Ignez. "The horses have been getting pie all day."

"Such a pity, can't you stop him?"

"I have no respect for a man with little children who can't control himself and think of them and the woman who bore them."

Contempt for the woman who continued to bear in such circumstances shot through the girl.

"If I had to live here always, I think I'd take to drink," she said. "It's so ugly. No creeks or ferns, and such scraggy timber. The people on these places have no more in them than a hen."

"Potterers and muddlers! It's harder for a woman than a man—with children always coming."

"I don't think a woman is a good mother to let them come if there's not a chance of success."

"Humph! You don't understand what it is to be married."

"I'd understand enough to keep out of it, if it's so awful."

"We'll see the great strokes you'll do when your time comes!"

In the morning Healey borrowed Ignez's hack and put a halter on one of the plough-horses, a brave old coacher, and then dressed himself in his shabby best suit.

"I might as well get a little to pay for the seed. No sense in letting the horse die for nothing now that the ploughing is done," he explained.

"When you need a plough-horse you'll have to buy one at a high price. More debt. You never learn sense. You're the worst..."

Healey rode away without response. He had learnt the value of silence.

The evening drew in cold and still drizzling, but Healey did not return. At dusk a forbidding-looking Assyrian hawker requested shelter—a reasonable demand, but the man's countenance made Mrs Healey fear murder, and she railed to Ignez of her husband's defection as a protector.

Ignez's music lesson was due on the following day. "I'll start early so I can get to the hotel and send Mr Healey home before he has all the money spent."

"I don't know what your father would say."

"It's an emergency. Father and mother never hold back in emergencies. I remember how they turned out the time the baby was lost on Ten Creeks Run."

"But a young girl going to a public house among drunken men!"

"Lots of girls marry drunken men. That's going a lot farther than seeing them at a pub. They won't lead me to drink. I'm not a boy."

She left at daybreak, having decided that the Assyrian was harmless. She had a poor nag, weak and unshod. She rode him off the metal, nevertheless he grew tender-footed and halting. The drizzle penetrated her hat and ran down her neck. Her collar collapsed, her gloves were soaked, and where the saddle's horns made hollows of her skirt the water reached her skin. She dismounted and walked to get warm, but the specially designed skirt could not be held in accordance with modesty in one hand while she dragged a protesting horse with the other, so she clambered up again. The narrow pipeclay hollows and stony ridges covered with stringybarks and underbrush, where a primitive homestead stood in a clearing every mile or two, seemed to have multiplied, but at length Goulburn came to view down a long slope, and finally she turned into the broad main street with a hotel at nearly every corner. Which one at present was draining the price of the Healeys' bread?

Throwing the reins over the post at Doolan's she went to a side entrance. On the asphalted floor of the veranda lay a youth but little her senior. He had been placed there on the previous evening when helpless, since there was a regulation against serving liquor to men already drunk. A cotton shirt and tattered coat were all that protected his upper half from the cold, dungarees encased his legs and the sockless ankles had a chafed ring above the rough boots. His hands were seamed and cracked from rough labour in the frost. He was a wood-carter, a patient bush lad to whom alcohol was something to warm him and an adventure in budding manliness.

While Ignez debated what she should do to rescue him, a richly dressed girl appeared in the doorway. Ignez knew her for the publican's petted only child, a musical prodigy being trained at the Convent.

"Do you know if Mr Lawrence Healey is here?"

"I'm sure I don't know. You'd better ring for the servants."

The reply was condescending, and aroused Ignez, who felt that Petty Doolan's voice was a mere squeak compared with her own.

"Aren't you going to do something about that poor boy?" she demanded.

"Papa does not wish me to come in contact with any of the people about the place."

"He might catch pneumonia lying there."

"Those bushwhackers are too hardy for that." Petty's glance at Ignez, stained and bedraggled, conveyed that she too was a bushwhacker.

"If he died, you'd be a murderer," said Ignez, her colour rising.

"Does he belong to you?"

"No, he belongs to you. You steal his money and then dress in velvet and put on airs with it while he lies there in danger of pneumonia."

"Papa will have you up if you say vulgar things about stealing."

"I'll tell everyone that you take the last penny from poor boys and then heave them out on the veranda all night in this weather."

Petty longed for her cab, but it did not come. Ignez pulled the bell vigorously. It brought the yardman.

"Is that boy alive, or is he poisoned?"

"She's blaming me for him," whimpered Petty, "and you'll have to go for the cab or I'll be late for my lesson."

"You had better see to the boy first or he might die," said Ignez, her blood up. "Shall I bring the doctor?"

"Doctor! be blowed! He's only soaked. He oughter been flung in the stable last night if he was too far gone to get home."

"Disgusting beast!" simpered Petty, recovering her poise as her cab appeared.

Ignez wandered inside and found the landlord. He informed her that Healey was there but too unwell to ride home just then. Ignez consented to her horse being stood in the yard as it was hours too early for her lesson.

"You're wet," observed Doolan, whose Family Hotel was called "the Mantrap" by many victimized women. "It's devilish cold. You'd better go to the fire," he added, and indicated a room at the end of a corridor.

In this the fire had not yet been laid. After shivering for a while Ignez sought the warmth of a bar parlour adjoining. Here she found her quarry, half tumbling from a chair and trying ineffectually to strike a match on the floor where the spittoons slopped in a sea of their rightful contents. The room was foul with the fumes of alcohol and stale tobacco and the evidence of a hard night. Two or three bar loafers were already playing cards. They were making jokes at Healey's expense and Ignez itched to correct them with her riding whip. Nothing could be done with Healey until he recovered, so she waited to dry herself. The spectacle filled her with sick revulsion. The landlady, finding her and recognizing that she was out of place, asked, "Why are you here? What do you want?"

"When will Mr Healey be fit to travel?"

"Some time, I'm afraid. He was very ill last night. If I had known he was inclined to over-indulge I might have stopped him."

Ignez's lip curled. It was not Mrs Doolan's trade to encourage sobriety, and she was known as a smart landlady.

"The drought is enough to drive anyone to take a drop," Mrs Doolan pursued, without arousing any response. She led the way to a room where her two younger sisters, the Misses Katchem, were making silk dresses. Ignez, unplacated, barely acknowledged the introduction to the stylish young women, and sat down. They returned to their chat of balls and dress and the advisability of wearing the best materials. Mrs Healey's best dress was quite out of fashion, Ignez reflected.

They gushed of the triumphs of Petty. Ignez learnt that she was to be sent later to the best teachers in Sydney. When the time came she departed for her own lesson without so much as a nod to her hostesses. After lunch, at old Mrs Wilson's select boarding-house near the cathedral, she returned to the Mantrap. Healey refused to bulge. The effects of the liquor were still too potent. Ignez composed herself to await his further recovery and to guard him from renewed poisoning, unconscious that there was anything unmaidenly in her procedure.

Two o'clock, three, four passed. Healey remained too disabled to mount his horse. The short winter day drew in. Squatters, dealers, drovers, farmers, auctioneers, butchers, yardmen, cadgers, loafers, touts and tag-rag representatives of all the classes that traffic in livestock, and their hangers-on—returned from the weekly sale. The Mantrap's bar was overflowing in two senses. Not a man but took a drink to warm himself, remarking that Goulburn was the —— coldest place in the world, one shouting for the other and the other returning the compliment. The saleyards had a bleak position and it was a biting day. The invitation of the fires was irresistible and many postponed home-going indefinitely.

The publican passed among his catch. He had the reputation of being a fleecer, was strong and brisk, and so far had not fallen to his own snares. He ordered more wood on the fires, threw a pack of cards on a table, remarked that it was "devilish cold outside", started a half-fuddled young fellow singing songs about true love, stirred up a few to serve as butts, and otherwise spread his nest for the sale-day harvest.

The parlours were full of men with flushed faces, some with bloated cheeks, all drinking, gabbling and craving diversion. The elaborately arranged hair, the gay dresses and affectations, which these men would have roughly condemned in wives or sisters, were attractive in the hotel women. These opulent people had more to stimulate them to be flattering entertainers than had the wives at home, harassed by children's wants and the strain of bringing two far ends together.

Ignez sat enduringly, raging inwardly. Two tap-room habitués came to issues through one calling the other an opprobrious name. Ignez wondered why men should be so touchy about being called bastards when they had no scruples about fathering them. One of these days she would write a book, and it would be of real doings.

Arthur Masters entered to discover the cause of the rumpus. His amusement changed to consternation as he caught sight of Ignez. He took the femininity of the Misses Katchem at a certain valuation—not a low one—and never felt in a hurry to leave the Mantrap when they gave themselves to impressing him, but Ignez Milford had struck a deeper chord in his manhood. She had the power to transform life and fill it with heroic possibilities. His impulse was to carry her out of the place at once. Then he halted. He could not point out the enormity of her presence there, for the enormity was not in her presence but in the scene itself. To impress upon Ignez any sense of defection in her behaviour would merely tarnish his own. He sought Doolan.

"The Missus took her in with the girls," he said, "but she poked herself back there. Hanging about after Healey. A queer sort of a girl."

"Queer in that sty! Get Healey on to his horse. If he's not able to ride I'll need your sulky." The tone was short.

Doolan sought to remedy his mistake by speedy action. The horses were forthcoming. Healey was contrite and always gentle, and set off at a great pace, but the barefooted horse sidled off the metal and could not be driven too hard. Masters overtook them as they left town and greeted them as though he had had no part in getting them started.

"I was thinking of you," he said to Ignez. "I have that book you were talking about by John Stuart Mill."

"Lovely! Will you lend it to me when you've read it?"

"I might," said Arthur, "seeing that I bought it on purpose. It looks like tough reading to me. I got a story to counteract it."

"Stories are only pap that never happens. You wait till I write a yarn. It'll be real."

"Golly, that'll be ripping! When are you going to start?"

"Any day."

"I can hardly write a letter, it's such hard work. How you'd fill a book is past me."

Healey was painfully sick and when they reached the shrubberied paddocks farther out Arthur gave him a rest. He put him and Ignez on the comfortable leaves at the foot of a big tree safe from the cutting blast and soon had a fire. "I often get off and make a fire to warm myself on a frosty night," he said with cheerful mendacity. Healey was in pain all through his frame and Masters helped him to the flask that Doolan had given him at parting.

"I don't know why anyone lives in this district," remarked Ignez.

"It's sounder land than anywhere, when the timber's killed, and very sweet. You'll get better flavoured meat here than off the heavy soils in warmer places," defended Arthur.

He was a native of Barralong, seven miles beyond Deep Creek. The property, which was choice for its area, had been owned by the Masters family since early days, and Arthur held his own position without knuckling under to anyone. The old man was dead, the other sons married and removed, and Arthur ran the place while his mother directed the house.

Warmed and fed with chocolates and biscuits from Arthur's pockets, Ignez went more comfortably. Deep Creek was soon reached. Masters tactfully refused to enter, but said he would reappear soon to hear what Ignez made of J. S. Mill on The Subjection of Women.

"Thank you for being so kind," she whispered, giving his hand a cordial squeeze as he lifted her from the saddle.

He wanted to tell her that she must never go to that pub again, but could not. She seemed to have the innocence of a child and the wisdom of a grandmother combined, so, cheeriness masking intensity, he contented himself with, "If there's anything you ever want, I'll go round the world to get it for you, if you'll let me." He held her hand till she drew it away, which she attributed to sympathy.

"I've done it again," groaned Larry, standing as if petrified in the cold.

"Never mind. Make a fresh start is all you can do." The girl led the horses to the stable and began to unsaddle. Healey came to with a start and followed her.

"If I was to cut my fingers off one by one, the pain would be nothing to the mental pain I feel."

Ignez flowed with sympathy, but was too young, too instinct with potential happiness really to understand his misery of despair and humiliation, his sick paralysing depression. How could one so potentially gifted, so richly endowed to give and to attract, in her immaturity understand one long broken by disaster and failure, scourged for old mistakes with punishment that could never end? Larry's intemperance in conjunction with continuing fatherhood and Mrs Healey's bitter condemnation were a sordid affront to the glamorous day-dreams that were beginning to invest the girl's adolescence.

"I'll be in presently," he said, and stood shivering and sick in the cold, with shattered nerves and wishing that by a miracle Dot would be silent.

The June day was damp and raw. Afternoon had made an undignified early retreat, dimming the sun, and the cold had driven the starving cattle to huddle in sheltered spots, but there was the cold-proof warmth of joy at Lagoon Valley. Grandma Labosseer of Coolooluk, Bool Bool, had written that within a few days Sylvia would be home for a long holiday. Nearly two years before Sylvia had gone to live with Grandma, who liked the companionship and help of her prettiest granddaughter. Blanche adored her younger sister and had sorely missed her presence. The prospect of reunion filled her with delight. The intervening days were too few for her festival of furbishing and contriving.

"We'd better take to the fowlhouse and give you a clear field," protested Dick, for nowhere in the house was there tolerance of dusty blucher boots.

Upon the glad day Mr and Mrs Mazere took the buggy to meet Sylvia, while Blanche surged into a day's cooking. At the crest of the engagement Allan delivered a supply of oven wood and emptied his jaws of a chunk of quince to announce the approach of Arthur Masters. The cook left her patties and ran out among the winter-bitten shrubs of the back garden to inform the dismounting horseman of Sylvia's arrival.

"Topping!" he laughed down at the girl with the rolling pin. "Have you room for an offsider?" He dismounted and followed her to the kitchen, where Allan was weighing ingredients, Philippa, aged eleven, was beating eggs, and Aubrey was scraping a dish. "Is Sylvia coming home for good?"

"Oh, no. It's nicer for her at Coolooluk, and I understand taking care of mother better."

"Bring Sylvia to the football match on Saturday."

"The horses are too skinny to use for pleasure."

"Old Tarpot's as fat as a whale. I'll lend him to you while Sylvia is here."

"You're very kind, but I don't know if we ought to," murmured Blanche.

Masters could not be prevailed upon to stay. Blanche's commendable affection for her sister and her housewifely demonstration lacked allure. An unaccustomed clouding of purpose had made him ride round by Lagoon Valley and Deep Creek. Blanche passed from his mind as he rode away and pondered again upon Ignez Milford. What on earth could a young girl find to interest her in a book about the subjection of women? He chuckled to think of such dry tack being sprung on the young men who were attracted by her vivacity. She must never be seen in the Mantrap's parlours again. He wanted to ask her to call on him when Healey's affliction overcame him, but was diffident. Ignez had a habit of asking probing questions, and he could not confess to her the lewdness of men regarding girls who broke the conventions.

He arrived at Deep Creek in time for tea. His intention of warning Ignez about the Mantrap's clientele was banished by a new scandal, which she had created by riding for the mail in Healey's saddle. This might have passed had she kept to the bridle track in the underbrush of sour currant and geebungs, or had she maintained a precarious sideways seat, but she had sat gamely astride and galloped along the main road for a mile. She had been seen by half a dozen neighbours, all censorious of this breach of the proprieties. Lizzie Humphreys had gone for the mail on the present day and lingered for a gossip with Mrs Harrap, who lived not far from the Healey mail-box. Peter Harrap, an obscene galoot who worked intermittently for Healey, had been loafing there, and Lizzie was agog with his pronouncements.

"Pete said he could see the lace on Miss Ignez's pants," giggled Lizzie to the whole family.

Only Masters noticed the confusion on the girl's face, which she covered with, "That's one of his flea-brained fibs. I held my skirt down."

"But you should not have been on the main road on a man's saddle. You know what a fellow like that would think."

"He hasn't anything to think with, but what I think of him might some day be a classic," said Ignez with a flash of inspiration beyond her experience.

"What's a classic?" inquired Lizzie.

"Mine's going to be irrefutable in its own backyard."

"Pete said a lot more," continued Lizzie. "All the men was talking about you, an' Pete said if it was his sister done it, he'd have her shut up so she couldn't go astray."

The sharp pain on the girl's face showed Arthur his own wisdom in reference to the Mantrap situation.

Ignez parried the shaft with "And such as that will be able to vote for Federation! I'll ride as I please."

"While you're with me," interposed Mrs Healey, "you must not have all the neighbours talking."

"Fancy having to live in a place where men talk like that! Cockatoos have much more intelligence. If Pete and his like all fell into Deep Creek and never came out, they'd be no loss."

"Lizzie will repeat everything you say, with additions," warned Mrs Healey, as Lizzie took the plates to the kitchen.

Masters summed up judicially. "I think girls ought to use a cross-saddle, but they need to be dressed properly for it. It does no good to run in the teeth of talent like Pete."

"Women have little chance of getting out of the way with their legs in a bag if a horse falls," admitted Healey.

"Someone will have to begin the fashion," said Ignez.

"You had better leave that to the Governor's lady," advised Masters.

His thoughts were on the matter all the way home under the frosty stars. He meditated with pleasure upon giving summary correction to Pete Harrap should opportunity occur. He would lend a horse or anything else to brighten things for Blanche, but the thought of Ignez spread a brightness along the ringing road all the way to Barralong.

Everything was in readiness for Sylvia as the wintry dusk crept across the hollows, and a Tableland wind hissed along the cleared flats. The children had shining red faces from the combined forces of soap, water, and frost. Allan and Philippa lamented the darkness that hid the bundle handkerchief they had flown on a sapling at the front gate. The dining table had such profusion and style as marked the visits of the Member for the district or those of the higher clergy. Mulligan escorted the buggy for the last furlong with a frenzied lullaloo of welcome as the children rushed round the verandas and threw open the flower-garden gate.

"Here I am," cried a laughing girlish voice.

"There'll be a terrible frost tonight," said Mrs Mazere. "I can feel it in all my bones."

"All signs of rain gone again," added Mazere.

"Dick, you're a man, and Allan so tall I hardly know him! Philippa's curls below her waist already, and Aubrey—how you all have changed!" The youthful soprano tones ran on. Blanche came last with a comprehensive hug to express her satisfaction. Mazere and Dick unharnessed old Suck-Suck. Mrs Mazere was busy with her parcels. They clattered into the dining-room where a fire of logs sang in the open white hearth, and the Reverend Mull, so named for the latest curate, was making his toilet on the rug.

"We want to see you in the light," said Allan boisterously, as Sylvia went to the fire, beating her hands together and complaining of the stinging cold. She was used to admiration and met their delight with happy laughter. Blanche unbuttoned the coat with its fashionable fur collar and removed a hat of velvet to disclose a picture that brought tears of joy and adoration to her eyes. Blanche was tall and inclined to bend forward from the waist; years might add angularity. Sylvia was petite and slender with a profusion of golden hair inclining to chestnut, an oval face with a daintily classical profile, and, over all, an expression of vivacious sweetness and happiness.

"You'd never think Blanche and Sylvia were sisters," was how Allan expressed it. "Blanche is so tall—and—and Sylvia is just lovely!"

Dick brought in Sylvia's luggage, half a dozen pieces. "I bet the porter expected a tip for this."

"The porters didn't get a chance. Some man in the carriage always took it all."

"It's nice to be a young girl," Mrs Mazere sighed. "When you're old no one will rush to carry your luggage."

"That was Malcolm Oswald who helped you at Goulburn," remarked Mazere.

"Yes," said Sylvia, and began to talk of the droughty aspect of the country, which, she said, was much worse than at Bool Bool.

At last Blanche was alone with her pet as they toasted themselves and exchanged confidences before the magnificent coals of the waning drawing-room fire. Blanche was excited by this elegant young lady. Two years ago her hands, like Blanche's, had shown the results of rough usage in sun and frost. Now they were enviably ladylike.

They retired to their bedroom. A kangaroo hide was the only covering on the boards. There was a much-tinkered bedstead, which had been procured for half a crown, a little chest of drawers and a tiny looking glass, all second-hand. The room contained about ten shillings worth of furniture. Packing cases, papered and painted, did duty in various capacities. There were a few photographs in home-made frames as ornaments. Sylvia held the kerosene lamp to one of these.

"Arthur Masters!"

"He came this afternoon and offered to lend us his buggy horse."

"That shows he's dead nuts on you."

"He's just a friend."

"A platonic one—I know them," laughed Sylvia. "Like one of those jam puffs, squashy inside. Let's get to bed quickly, or I'll freeze. It's much colder here than at Coolooluk. It's this terrible wind."

When they were cuddled together for warmth Sylvia continued, "Couldn't we go to the football match on Saturday?"

"The horses are so poor. I don't like to use them for pleasure."

"You said Arthur would lend his."

"Father mightn't let us accept."

"Does he object to Arthur? Is it serious, or have you just got him on a string for practice?"

"That would be wicked! Poor Arthur!" Blanche's tone betrayed her.

"He only has an Oswald's Ridges farm, hasn't he? How did he start coming here? We usen't to know the Finnegans or Barralong people before I went to Grandma."

"Father sold him a couple of heifers and as it was tea-time he was invited to stay. After that he kept coming. He talks about organizing a co-operative dairy for the district."

"You mean like that one that used to be near the church, where the manager got drunk and left the pigs to die in the heat?"

"No!" Blanche's voice was scornful. "Arthur never touches a drop. He'd start something efficient."

"He'd need to...Dear me, isn't the house terribly poor! It makes me want to cry."

"I slaved to make it nice for you."

"I can see you did. I mean the things that you can't help."

"There's such a terrible drought."

"It's poor land, that's the trouble. Supposing I got married, then you could live with me. Things are better up the country. Father just the same—nothing thriving?"

"No one could thrive in this drought?"

"Yes, but uncle says he's a bad manager. Wouldn't you hate to settle down to one of these awful little cockatoo farms, rearing a few fowls and poddy calves, and dragging in a cowyard?"

"A woman is never let into the Masters cowyard or dairy."

"I see I'll have to be nice to my brother Arthur."

"I'm only showing it's not the places, it's the people."

"Poor places make poor people, Grandma says. Poor mother, complaining day and night as usual, I suppose?"

"Well, you're so pretty you ought to marry a prince, I'm sure. It'd be a pity to waste yourself on Oswald's Ridges."

"Malcolm Oswald said he might go to the football match."

"Is he in love with you?"

"I only met him on the train, silly! But he seems like all the men. The football match would be an outing."

"Arthur was just dying for an excuse to come for us."

"Tell me about Ignez Milford."

"She's supposed to be very clever, but no good in the house."

"Isn't she? In a letter to Grandma, Mother said she never saw a girl so quick, and that she makes her own frocks and riding habits already and can bake splendid bread if she sets her mind to it."

"Yes, but she thinks her mind's above such tame-hen work. She's not a bit womanly."

"What's she look like?"

"Some think she's wonderful, and others call her quite plain. She has a different kind of face, but you like to watch it. She says the terriblest things straight out to men as well as to women, but I don't think she would go astray with men—she's not fast that way."

"Is she really so clever at the piano?"

"She plays that dull stuff without a tune. Father says he would as soon have the tune the old cow died of."

"And her name—no one knows how to pronounce it. Where did she get it?"

"That's a good sign of what she's like. Ignez is merely foreign for Agnes."

"Agnes is a horrible name. No wonder she wants to change it."

"People call it Ignez, like it's spelt, and that's worse, like a lizard of some sort. She has always to be telling them to call it Eenyez, or Eenyeth is the tony Castilian way, she says. I'll ask her to stay here while you're home. It'll make more fun."

"That'll be topping. Let's go to the football match, but I'm sleepy now."

In the morning Ignez galloped over to see Sylvia and settled the matter of a horse for pleasure. Her own hack, Deerfoot, a ladylike waler, would go in harness. Ignez responded to the Mazeres' social needs as eagerly as if they were her own. She was spontaneous and sympathetic, as full of energy as generosity, and always felt that problems were to be solved by more effort on her part, unaware that she was recklessly pouring out unusual personal gifts in the process. She added the Mazeres' preoccupations to her duties at Deep Creek, and her musical studies and practice were squeezed into any cranny of time, a procedure fatal to serious voice or piano culture, but no one there understood this.

Immediately following dinner on Saturday the young people set off to the football match. The glittering sunshine could not warm the air driven across the high tableland by the Antarctic's bellows to sting young cheeks to brighter hue and furrow the long coat of the horse. Magpies and rosellas rose before them from the arid paddocks dotted with stumps like grave-stones or ringbarked trees that stood naked and gibbet-like. The underbrush scraped the wheels as they travelled, laughing and chattering, undepressed by the bad season. A final set of sliprails let them into the football ground upon a stock reserve at Kaligda. Play had already started on a cleared space surrounded by a dense wall of briers. The boys protected the horse with the rug and approaching the game, while the girls sought acquaintances in the sheltered bays among the briers.

Tot and Elsie Norton were stylish girls and warmly welcomed the Mazeres, who were newcomers to these gatherings because the mesdames Mazere and Healey were still inclined to be aloof, remembering their up-country status. The Norton place was in the direction of Arthur Masters's. Tot and Elsie were saddled with another near neighbour, Bridgit Finnegan. The Norton horses were too poor for pleasure and one had been borrowed from old Finnegan, a more thrifty husbandman. He raged about this waste of horseflesh, but Mick, his son, as well as Bridgit, was against him so he was defeated.

Wyndham Norton, known as Wynd for short, came to greet the new arrivals as soon as the game permitted, and looked on Sylvia with a delight that was marked by Bridgit, whose heart was Wynd's for keeps. Wynd played cricket and football in a way that made him popular with the youths, danced and sang equally acceptably to the girls, and was as cheerful and normal a young man as could be found from Oswald's Ridges to Crookwell. He looked well in his jersey, and when among the girls his eyes were as full of admiration as his mouth of compliments. He did not lack a pleasant word for Bridgit, a roomy clodhopper with unmanageable hands and feet, though her pleased reception of any word of his was warning him of danger. A whistle recalled him to the game. His place with the visitors was taken by Mick Finnegan, Bridgit's brother, who was on the field as a spare. He knew Blanche, and was introduced to Sylvia and Ignez. He was a reader of standard works on agriculture and history, and a natural desire to discuss his knowledge and a delight in literary language made him seem pedantic among those who read nothing but the local paper. They took revenge for their own inferiority by nicknaming him "the Professor". Sylvia's beauty dazzled him. Under its spell he found himself in conversation with Ignez. Sylvia had remarked on the dreadful appearance of the country and Ignez said that people should conserve fodder.

"You're right, Miss Milford," agreed Finnegan. "Australians need to learn how to farm. The pig-rooting and cockatoo-scratching stage is past." He waved a commodious hand to indicate the ragged watershed. "It's time to practise more concentrative and economic methods than those of the careless days. Once, if the wheat was a failure the settler put in potatoes. If grubs ate these, he could turn to a few cows; when drought dried up the dairying there were sheep. Stumps in the middle of the furrows or acres wasted in headlands and wash-aways were of no account."

"In the wet seasons they squeak about footrot and fluke; in the dry ones they squeak about everything dying of drought. My uncle says there ought to be a great reservoir in the mountains that would let the water gravitate all over the lower country, but no one listens to him."

No one listened to Mr Finnegan and Miss Milford except with a mild sense of ridicule. Mick himself had more hankering for Sylvia's beauty as an audience than for Ignez's intelligence. The piercing wind was a penalty to the onlookers. Sylvia suggested a walk as relief and they ascended Baby Mountain. Appropriately named, it rose up alone from little ridges. Its crest, easily attained, commanded a fine view. In the foreground a few steel-grey roofs peeped above jungles of briers red with berries; a school-house and a church topped a middle ridge; the horizon was a wide circle of blue hills with Lake George as a jewel in the centre. The drought was emptying the lake and reviving anecdotes of early days when it had not existed at all.

"Isn't it lovely! I wish I could paint!" exclaimed Ignez.

"It's so cold it's painting my nose as blue as itself," said Sylvia. Everyone laughed and watched her with more interest than the scenery as she snuggled into her fur collar and lifted her skirts from the snagging logs and sticks of the thickly fallen timber.

As they neared the football field again, Sylvia whispered to Blanche, "He's come." Her colour heightened and she turned with stressed attention to Finnegan.

"The aristocracy seems to have descended upon us," he observed with reference to a man leaning over the split-rail fence watching the game and smoking an unusual pipe. Not yet dismounted was a younger man on a flighty racing filly with a heavy rug strapped to the pommel to protect her clipped body. "The celebrated Malcolm Oswald of Cooee."

"What's he celebrated for?" inquired Ignez.

"He rides half-broken colts over wire fences, and that, Miss Milford, makes him much more celebrated than if he were the author of an encyclopaedia on agriculture."

"It's a pity that professors are often so dull while those that kill time at the races generally look more like real men."

"Oswald has a weakness for pretty faces. You'll always see one of his horses tied outside a house where there's a pretty girl."

"Is it the same girl or a succession?"

"He likes them in rotation," continued Finnegan, delighted to say this before Elsie Norton. He watched her face, but her expression was studiously detached. An Oswald thoroughbred was so often hitched outside Norton's that the gossips were saying, "Elsie might catch him yet if she watches herself."

Oswald remained leaning over the fence with one or two men, apparently engrossed in the play, while Sylvia kept her face in another direction. When at length she turned towards him with a scarcely perceptible bow, he pocketed his pipe with an alacrity at variance with his manner, and approached in the stiff gait of one racked by rough riding.

"Well, Miss Mazere, you got home safely, I see," he remarked, with a pleasant twinkle in his eyes.

"You are old acquaintances," said Elsie Norton. "You never mentioned it, Mr Oswald."

"Hadn't the pleasure of seeing you since."

Sylvia added amiably, "I met Mr Oswald on the train, and found him a good porter."

"Thank you. I'm hoping for further engagements." Oswald bowed mockingly. He could make fewer words go farther than any man to whom he said goodday.

"Doesn't he beat Gallagher, like a moth to a candle to every new pretty face!" Finnegan did not advance his own cause by this aside to Elsie. She kept her attention on the Mazere party, startled by the advent of a new star in Oswald's firmament.

"Hullo! Hullo!" cried Wynd Norton, approaching with a ball under his arm. "Who did you bring with you?"

"Hullo, Wynd! Gave 'em a good licking," responded Oswald. "I brought my young cousin from Monaro." The lad drew near with the men with whom he had been left in the first place. "My cousin, Malcolm Timson."

Ignez greeted him as a Monaro acquaintance, and interest took a fresh focus as the youth entered the circle. He, too, was in corduroy breeks and leggings and long spurs; he, too, was a superb horseman, but years had not yet stiffened his action; he was lithe and quick in his movements.

Elsie, with attention concentrated on Oswald and Sylvia, noted happily that Sylvia's glances had sweet wonder for the new arrival. Sylvia was beholding a young man who stood six feet one in his socks and was proudly proportioned from his well-cut head to his long sunburnt hands with the filbert nails. His black hair showed a crisp white parting as he raised his hat. His brows were level and delicate, his nose well-formed and of dignified cast. His lips were firm and tranquil and smudged by a small moustache, hastening to be adult and in the fashion up the country, where entirely shaven faces were the exception.

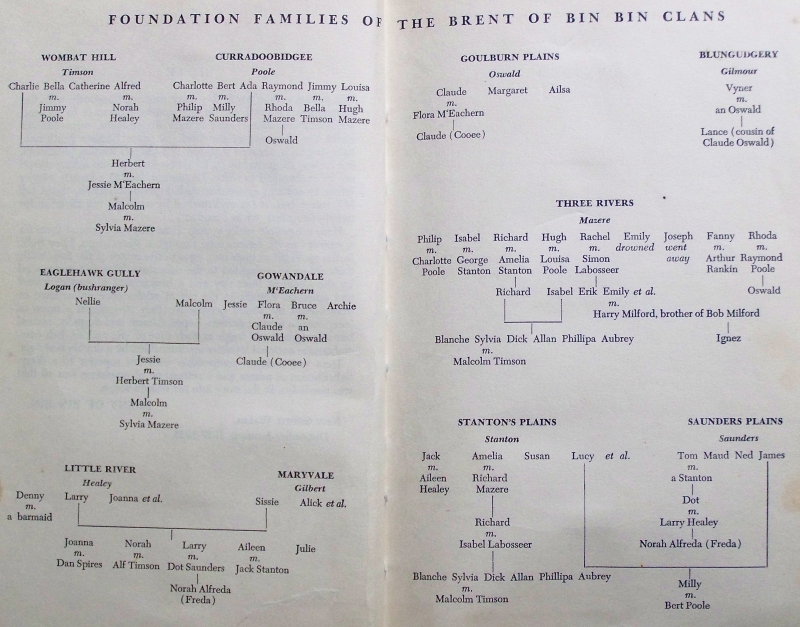

The old hands of Monaro and Bool Bool maintained that young Malcolm Timson was the spit of his great-uncle, Bert Poole of Curradoobidgee, with an added merriment of manner and a kink in his hair contributed by his grandfather, Malcolm M'Eachern, son of the old original of Gowandale.

The locals had beaten their guests by six goals to four. Everyone was in haste to get away, the afternoon was raw, and some spectators had twenty miles to go. Masters's men made off to the milking, leaving Arthur free for the evening.

"Well, you gave 'em a great walloping," said Oswald as Masters came up, wiping the perspiration from his face.

Arthur and Wynd were the district champions, but Wynd was off his game because of a sprained wrist earned in a previous contest, and Masters had been compelled to unusual exertion in his forward play. He looked towards Ignez for approval of his performance.

"You were a regular hummer," she conceded.

Finnegan asked Sylvia her opinion of the play.

"You mean that little scuffle at the end of the flat while we went for a walk?"

Wynd met the provocation of her glance with hearty laughter.

"You'd better put on your coat, the wind is like a knife, and you're so hot," said Blanche to Arthur.

"You're like a mother," he responded, without heeding her advice. Blanche was not attempting motherliness and felt disappointed as she invited Wynd and Arthur to tea. Masters accepted readily. "I have Tarpot with me," he remarked for Blanche alone. That was better.

Wynd said he was with the Finnegans, so Sylvia turned charmingly to Bridgit. "Won't you come too? I've hardly had a word with you, and I'm sure your brother hasn't finished his debate with Miss Milford."

Blanche was dubious about the Finnegans. Mazere referred to the old man as a God-forsaken old bogtrotter as bigoted as a bull, but Miss Finnegan accepted effusively. By lending the Norton's a horse—about which Da had made such an unholy fuss—she felt she was to ascend socially.

Arthur and Wynd then escorted the visiting team to the pub about half a mile away to treat them to a nip, politely called refreshments, before their bracing homeward drive while they heard the story of the Wellington boot left by the Hall gang of bushrangers one day in the sixties when they shot the township constable and scribbled the first line of a legend on the little settlement's blank slate. A number of other young men remained with the girls. They fed the fire and stood round it chattering and dodging the gusts of smoke.

Sylvia invited Oswald and his namesake for the evening. Ignez was immediately friendly with Malcolm the younger, so like his famous uncle, Bert Poole, who had married her dearest friend Milly Saunders. Ignez further claimed him as almost a cousin because her uncle, Harry Milford, had married a Miss Labosseer, and that Miss Labosseer's two uncles each had married a great-aunt of Malcolm. Sylvia insisted that she had closer connection and began to trace it.

"Here come Wynd and Arthur; now we can go home, and mother and father can straighten it out. Who married this and who was grandfather of what is all that old people think about," said Dick.

"In any case we're near enough to know our Christian names," drawled Oswald. He had not yet been to Lagoon Valley but was sure of a welcome. The cockies were prouder than stray members of the big land-holding cliques; they did not risk social slights by getting in the way of richer men's second-grade hospitality, though the said stray members accepted the cockies' best complacently.

The Nortons were pleased to go to Lagoon Valley, also for the first time, though embarrassed by the Finnegans. Oswald suggested that Dick could try his colt, and Dick decamped at once leaving his seat in the buggy beside Sylvia. This suggested other changes, but none that were satisfactory to Bridgit, Elsie, or Blanche.

Mrs Mazere, with the aid of Aubrey and Philippa, had the meal ready. Masters shifted an extra table and chairs; Sylvia took charge of the women guests. Wynd helped the boys with the horses. To have Arthur thus active domestically made Blanche happy.

"So you and the Professor had a good time," he teased Ignez.

"He has something in his head at all events," she replied.

"He'll never be happy till he gets Elsie Norton."

"And Elsie makes fun of him," added Blanche.

"That's a common symptom," interposed Mrs Mazere. "I couldn't count all the girls I've heard ridiculing their future husbands."

"So you reckon it's a good symptom. Do you ever ridicule me?" Arthur demanded of Ignez, with a broad grin. Blanche felt this question was really for herself, but addressed to the younger girl as a subterfuge.

Mrs Mazere and Blanche were industrious providers and the table was well laden in spite of the lean harvest. Mrs Mazere was animated, her pains forgotten. To disperse hospitality had likewise made a pleasant change in Mazere's worry about the drought. Aubrey was rewarded for his home-staying by a seat beside Sylvia to the displacement of an older admirer and the lively delight of the child. Youthful merriment was as robust as the appetites sharpened by exercise in the keen wind.

While Blanche held the company up to know if they took milk and sugar in their tea, Sylvia reopened the matter of Timson's relationship. Mazere settled it.

"Your grandmother was Ada Poole," he began to Timson. "That makes old Boko Poole of Curradoobidgee your great-grandfather. Your grandmother had two sisters, Charlotte and Louisa, who were married to two sons of the original Mazere of Three Rivers. Those two Mazeres were uncles of Mrs Mazere and me, as we are cousins."

"It dizzies me," murmured Elsie Norton, who was sitting on Mazere's right.

"It's not close enough for me to get into young Timson's will," guffawed Mazere.

Oswald contended that he came in higher up the tree, being the son of Flora M'Eachern, but his claims were dismissed with laughter because his aunt, Jessie M'Eachern, had thrown Great-uncle Hugh Mazere over to remain an old maid.

"It doesn't bring you very near to the Mazeres," said Oswald's host, "but it brings you near enough to have another cup of tea and another slice of beef. It's not very fat, but that can't be helped these days."

"Thanks, on the strength of the family connection." Oswald's plate and cup were refilled.

Talk pursued the difficulty of finding a beast fit to kill, until it was put on the road of politics by Michael Finnegan. The federation of the colonies into a commonwealth or dominion was the liveliest question of the hour. Ignez said that the matter should be postponed until women could vote upon it.

"Are you going to vote for woman suffrage?" she demanded of Finnegan.

"I am not," he promptly replied. "It's a woman's glory to serve. As soon as women begin to take the places of men a nation is doomed."

"Men don't flute like that when women are labouring in the cowyards." Bridgit was more at home in a cowyard than in a drawing-room, so Wynd suppressed his inward bubbling, and Mazere tried to change the subject.

"It's not in trifling physical labour that the decadence is dangerous, but in women trying to ape men's minds," continued Mr Finnegan, but Mrs Mazere pressed him to a further helping of pudding, and Blanche tried to pour him a fourth cup of tea, and while he was defending himself from them Ignez planted what Wynd called a sollicker.

"You'd think that men were afflicted with whiskers on their brains as well as on their faces, the way you talk. There's no sex in sheer intellect."

Arthur winked at Ignez, which comforted her. Elsie Norton laughed in silvery affectation, and Wynd inquired of Allan the difference between a dead bee and a sick lion. In the drawing-room later the Professor and Ignez had to take refuge in each other's intelligence because one did not sing and the other was ruled out as a pianist in favour of Tottie Norton and Sylvia, whose repertoires were more popular.

Many an animal was shivering in its final torture in the demolishing winds over the dry frosty tracts, but their suffering did not penetrate to the comfort of the piled log fires in drawing-room, dining-room, and kitchen, where the company was divided for certain games. Loud were the songs and laughter. "The Deathless Army", "The Midshipmite", "Sailing", "They All Love Jack", "Anchored", and a dozen other current ballads were rendered by Oswald, Dick, and Wynd. The Misses Norton and Mazere contributed "Whispering Hope", "The Valley by the Sea", and "The Maid of the Mill". Sylvia aroused excessive delight with "The Miller and the Maid", "Barney O'Hea", "Annie Laurie", and "Scenes that are Brightest". "Father O'Flynn", "Off to Philadelphia", "The Rhine Wine", etc. etc. were bawled as choruses. Then Sylvia, Dick and Masters insisted that Ignez should sing "The Carnival" and "Daddy" in her big unsteady young contralto, which the unknowing were inclined to ridicule. She added another song about a last waltz, a rose that was dead and a love that was fled, which filled the amorous with yearning, and made her elderly and unmusical hosts wonder why a lively girl who knew nothing of the troubles of life should choose such dismal wash.

High spirits bubbled during a lavish supper at eleven o'clock, after which the visitors turned out in the frost. All were pressed to stay the night, but refused with effusive thanks and ardent hopes of early future meetings.

Aubrey and Philippa had been asleep for some time. The elders left the fire to the young people, who held the usual post-mortem on their guests.

"That great walloping Bridgit never said a word," giggled Allan.

"That silly old Mick grabbed her share of the conversation. He needs a good sneeze to clear his head. All the same he's going to lend me a book of poetry," commented Dick.

"I've taken a fancy to Bridgit," announced Sylvia.

"She's not such a twicer as Tottie Norton," conceded Dick. "Tottie agrees with everyone, and that can't work out right."

"When Wynd is singing Bridgit's lips keep moving with the words." Ignez's tone was thoughtful.

"She'd just suit him," decided Blanche. "She would paddle in the cowyard while Wynd ran about and enjoyed himself."

"What did you think of the Malcolms?" inquired Sylvia, coming to her special interest.

"I wish I had their horses," said Dick.

"Me too," agreed Allan. "That filly's a clinker—too much toe for anything about here. I hope they get spoony on Sylvia, then we can ride their mokes."

"I'm ashamed of you, Allan," came from Sylvia in laughing rebuke, free from sting.

"When I grow up," announced Allan, "I'm dead certain I'll never get spoony on the girls. The men think the girls are dead shook on them, and all the time the girls are only poking borak."

"The way that Tottie does her hair makes it look a terrible lot," began Blanche.

Mazere père shouted from his room, "Get to bed! Get to bed!" The boys obeyed, leaving the girls to whisper their final dissections.

"Everyone says Malcolm Oswald is smitten on Elsie Norton," pursued Blanche.

Sylvia yawned. She was continually meeting men whom rumour credited to this and to that girl, but they always looked at her as Malcolm Oswald had done at their first encounter and connived at a second meeting as soon as possible. In any case she was no longer interested in the elder Malcolm.

"Dear me, I thought it was Bert Poole, when that young Timson came in tonight," remarked Mrs Mazere, as she and her husband began their summary of the evening. "What is the old yarn about the Timsons and Healeys?"

"Old Healey, the original man-eater of Little River, was said to have bought his wife from old Logan the Bushranger. Nellie Logan, supposed to be half-sister of Larry Healey's father, married Malcolm M'Eachern. Larry Healey's father and this young Timson's mother are first cousins, and Logan the bushranger is this boy's great-grandfather."

"If that's his pedigree he's not worth running after."

"Hoh! If you went into it, where would you find a better? A few out of any family may be good flowery potatoes. Most of the others have green frostbite."

"The old M'Eacherns hunted the son when he married Nellie Logan."

"But here's this young fellow riding about with his cousin. Any of the geebungs will jump at him."

"Old Logan the bushranger!"

"What are the aristocracy of England but the descendants of robbers, and many of them bastards at that, if you read history?"

"Well, we don't come from people like that." Mrs Mazere's tone was self-satisfied.

"And where is Dick today compared with young Timson? What good is the Mazere breed if it can't get ahead of the other fellow? When Timson comes to settle down you'll see it won't be with any of the cockies' daughters of Oswald's Ridges. The very name means Oswald's leavings when the old original squatted on his early holding. That Norton piece thinks she'll catch Oswald. He finds it a good place to loaf."

"Arthur Masters might be the best of the lot."

"There's not a man among them fit to wipe Masters's boots."

"He has lent Blanche his buggy horse."

"Blanche is the wrong colour. He thinks no more of her than he does of the old bogtrotter's daughter, and she has her eye on young Norton."

"When he gets this city billet he's after he won't want to be saddled with a lump like Bridgit."

"More likely when he's had his twopenny-halfpenny job a year or two he'll be glad to limp home to Bridgit—with a good slice of farm saved by the old potato, griping to put penny to penny. All these young fellows'll find that they're only fit for unskilled labour in the city, the same as in the country, and many a time they'll wish they were riding about Oswald's Ridges grinning at the girls."

"Mr Oswald seems a pleasant man," was all that Mrs Mazere could oppose to this.

"Is it likely he wouldn't be when he comes to loaf with the girls and have a feed? The difference between him and Masters is that Masters does his share of work like a man, and Oswald pays a man to do his while he leans over the fences at cricket matches, or sits on old Norton's sofa while his horse is tied outside."

"I'm sure I wish I had someone to do my work for me."

"Hoh! That's not the point."

"It's a plain point to me," retorted Mrs Mazere.

Her husband retreated by way of a final shout to the young people, "Get to bed! Get to bed!"

Oswald let Wynd escape from Bridgit on the colt while he took the back seat in the buggy beside Elsie. With three against him Michael was powerless to prevent this arrangement. Wynd rode with the younger Malcolm and Masters near enough to the vehicle for chatter. Oswald's place, named Cooee, was many miles from Norton's, so both Malcolms were persuaded to turn in with the Nortons. Tomorrow was good old Sunday, free from major works, so Masters and the Finnegans also yielded to more tea and talk before going home, and it was very late or early before the Norton household was in bed and Elsie free to sort her thoughts.