a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The Moon Men Author: Edgar Rice Burroughs * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 0500221h.html Language: English Date first posted: Feb 2005 Most recent update: Jul 2015 This eBook was produced by Colin Choat and Roy Glashan. Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html To contact Project Gutenberg of Australia go to http://gutenberg.net.au

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

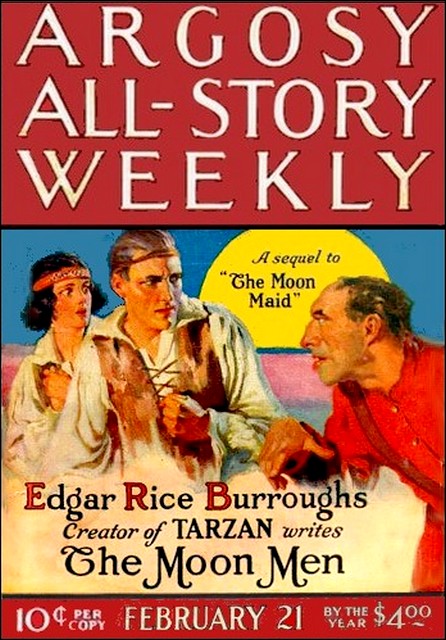

Argosy All-Story Weekly, February 21, 1925, with first part of "The Moon Men"

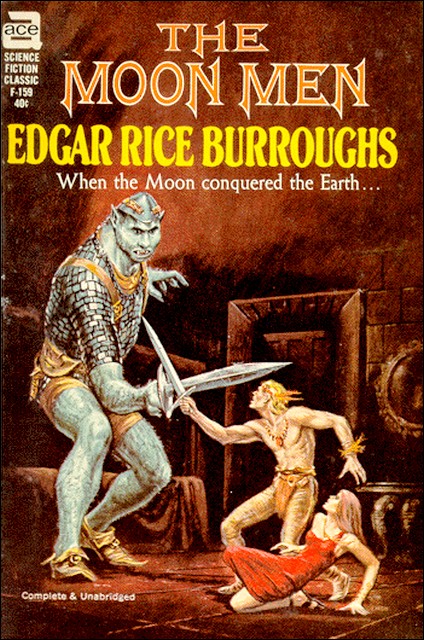

"The Moon Men," Ace paperback edition

IT was early in March, 1969, that I set out from my bleak camp on the desolate shore some fifty miles southeast of Herschel Island after polar bear. I had come into the Arctic the year before to enjoy the first real vacation that I had ever had. The definite close of the Great War, in April two years before, had left an exhausted world at peace—a condition that had never before existed and with which we did not know how to cope.

I think that we all felt lost without war—I know that I did; but I managed to keep pretty busy with the changes that peace brought to my bureau, the Bureau of Communications, readjusting its activities to the necessities of world trade uninfluenced by war. During my entire official life I had had to combine the two—communications for war and communications for commerce, so the adjustment was really not a Herculean task. It took a little time, that was all, and after it was a fairly well accomplished fact I asked for an indefinite leave, which was granted.

My companions of the hunt were three Eskimos, the youngest of whom, a boy of nineteen, had never before seen a white man, so absolutely had the last twenty years of the Great War annihilated the meager trade that had formerly been carried on between their scattered settlements and the more favored lands of so-called civilization.

But this is not a story of my thrilling experiences in the rediscovery of the Arctic regions. It is, rather, merely in way of explanation as to how I came to meet him again after a lapse of some two years.

We had ventured some little distance from shore when I, who was in the lead, sighted a bear far ahead. I had scaled a hummock of rough and jagged ice when I made the discovery and, motioning to my companion to follow me, I slid and stumbled to the comparatively level stretch of a broad floe beyond, across which I ran toward another icy barrier that shut off my view of the bear. As I reached it I turned to look back for my companions, but they were not yet in sight. As a matter of fact I never saw them again.

The whole mass of ice was in movement, grinding and cracking; but I was so accustomed to this that I gave the matter little heed until I had reached the summit of the second ridge, from which I had another view of the bear which I could see was moving directly toward me, though still at a considerable distance. Then I looked back again for my fellows. They were no where in sight, but I saw something else that filled me with consternation—the floe had split directly at the first hummock and I was now separated from the mainland by an ever widening lane of icy water. What became of the three Eskimos I never knew, unless the floe parted directly beneath their feet and engulfed them. It scarcely seems credible to me, even with my limited experience in the Arctics, but if it was not that which snatched them forever from my sight, what was it?

I now turned my attention once more to the bear. He had evidently seen me and assumed that I was prey for he was coming straight toward me at a rather rapid gait. The ominous cracking and groaning of the ice increased, and to my dismay I saw that it was rapidly breaking up all about me and as far as I could see in all directions great floes and little floes were rising and falling as upon the bosom of a long, rolling swell.

Presently a lane of water opened between the bear and me, but the great fellow never paused. Slipping into the water he swam the gap and clambered out upon the huge floe upon which I tossed. He was over two hundred yards away, but I covered his left shoulder with the top of my sight and fired. I hit him and he let out an awful roar and came for me on a run. Just as I was about to fire again the floe split once more directly in front of him and he went into the water clear out of sight for a moment.

When he reappeared I fired again and missed. Then he started to crawl out on my diminished floe once more. Again I fired. This time I broke his shoulder, yet still he managed to clamber onto my floe and advance toward me. I thought that he would never die until he had reached me and wreaked his vengeance upon me, for though I pumped bullet after bullet into him he continued to advance, though at last he barely dragged himself forward, growling and grimacing horribly. He wasn't ten feet from me when once more my floe split directly between me and the bear and at the foot of the ridge upon which I stood, which now turned completely over, precipitating me into the water a few feet from the great, growling beast. I turned and tried to scramble back onto the floe from which I had been thrown, but its sides were far too precipitous and there was no other that I could possibly reach, except that upon which the bear lay grimacing at me. I had clung to my rifle and without more ado I struck out for a side of the floe a few yards from the spot where the beast lay apparently waiting for me.

He never moved while I scrambled up on it, except to turn his head so that he was always glaring at me. He did not come toward me and I determined not to fire at him again until he did, for I had discovered that my bullets seemed only to infuriate him. The art of big game hunting had been practically dead for years as only rifles and ammunition for the killing of men had been manufactured. Being in the government service I had found no difficulty in obtaining a permit to bear arms for hunting purposes, but the government owned all the firearms and when they came to issue me what I required, there was nothing to be had but the ordinary service rifle as perfected at the time of the close of the Great War, in 1967. It was a great man-killer, but it was not heavy enough for big game.

The water lanes about us were now opening up at an appalling rate, and there was a decided movement of the ice toward the open sea, and there I was alone, soaked to the skin, in a temperature around zero, bobbing about in the Arctic Ocean marooned on a half acre of ice, with a wounded and infuriated polar bear, which appeared to me at this close range to be about the size of the First Presbyterian church at home.

I don't know how long it was after that that I lost consciousness. When I opened my eyes again I found myself in a nice, white iron cot in the sick bay of a cruiser of the newly formed International Peace Fleet which patrolled and policed the world. A hospital steward and a medical officer were standing at one side of my cot looking down at me, while at the foot was a fine looking man in the uniform of an admiral. I recognized him at once.

"Ah," I said, in what could have been little more than a whisper, "you have come to tell me the story of Julian 9th. You promised, you know, and I shall hold you to it."

He smiled. "You have a good memory. When you are out of this I'll keep my promise."

I lapsed immediately into unconsciousness again, they told me afterward, but the next morning I awoke refreshed and except for having been slightly frosted about the nose and cheeks, none the worse for my experience. That evening I was seated in the admiral's cabin, a Scotch highball, the principal ingredients of which were made in Kansas, at my elbow, and the admiral opposite me.

"It was certainly a fortuitous circumstance for me that you chanced to be cruising about over the Arctic just when you were," I had remarked. "Captain Drake tells me that when the lookout sighted me the bear was crawling toward me; but that when you finally dropped low enough to land a man on the floe the beast was dead less than a foot from me. It was a close shave, and I am mighty thankful to you and to the cause, whatever it may have been, that brought you to the spot."

"That is the first thing that I must speak to you about," he replied. "I was searching for you. Washington knew, of course, about where you expected to camp, for you had explained your plans quite in detail to your secretary before you left, and so when the President wanted you I was dispatched immediately to find you. In fact, I requested the assignment when I received instructions to dispatch a ship in search of you. In the first place I wished to renew our acquaintance and also to cruise to this part of the world, where I had never before chanced to be."

"The President wanted me!" I repeated.

"Yes, Secretary of Commerce White died on the fifteenth and the President desires that you accept the portfolio."

"Interesting, indeed," I replied; "but not half so interesting as the story of Julian 9th, I am sure."

He laughed good naturedly. "Very well," he exclaimed; "here goes!"

Let me preface this story, as I did the other that I told you on board the liner Harding two years ago, with the urgent request that you attempt to keep constantly in mind the theory that there is no such thing as time—that there is no past and no future—that there is only now, there never has been anything but now and there never will be anything but now. It is a theory analogous to that which stipulates that there is no such thing as space. There may be those who think that they understand it, but I am not one of them. I simply know what I know—I do not try to account for it. As easily as I recall events in this incarnation do I recall events in previous incarnations; but, far more remarkable, similarly do I recall, or should I say foresee? events in incarnations of the future. No, I do not foresee them—I have lived them.

I have told you of the attempt made to reach Mars in the Barsoom and of how it was thwarted by Lieutenant Commander Orthis. That was in the year 2026. You will recall that Orthis, through hatred and jealousy of Julian 5th, wrecked the engines of the Barsoom, necessitating a landing upon the moon, and of how the ship was drawn into the mouth of a great lunar crater and through the crust of our satellite to the world within.

After being captured by the Va-gas, human quadrupeds of the moon's interior, Julian 5th escaped with Nah-ee-lah, Princess of Laythe, daughter of a race of lunar mortals similar to ourselves, while Orthis made friends of the Kalkars, or Thinkers, another lunar human race. Orthis taught the Kalkars, who were enemies of the people of Laythe, to manufacture gunpowder, shells and cannon, and with these attacked and destroyed Laythe.

Julian 5th and Nah-ee-lah, the moon maid, escaped from the burning city and later were picked up by the Barsoom which had been repaired by Norton, a young ensign, who with two other officers had remained aboard. Ten years after they had landed upon the inner surface of the moon Julian 5th and his companions brought the Barsoom to dock safely at the city of Washington, leaving Lieutenant-Commander Orthis in the moon.

Julian 5th and the Princess Nah-ee-lah were married and in that same year, 2036, a son was born to them and was called Julian 6th. He was the great-grandfather of Julian 9th for whose story you have asked me, and in whom I lived again in the twenty-second century.

For some reason no further attempts were made to reach Mars, with whom we had been in radio communication for years. Possibly it was due to the rise of a religious cult which preached against all forms of scientific progress and which by political pressure was able to mold and influence several successive weak administrations of a notoriously weak party that had had its origin nearly a century before in a group of peace-at-any-price men.

It was they who advocated the total disarmament of the world, which would have meant disbanding the International Peace Fleet forces, the scrapping of all arms and ammunition, and the destruction of the few munition plants operated by the governments of the United States and Great Britain, who now jointly ruled the world. It was England's king who saved us from the full disaster of this mad policy, though the weaklings of this country aided and abetted by the weaklings of Great Britain succeeded in cutting the peace fleet in two, one half of it being turned over to the merchant marine, in reducing the number of munition factories and in scrapping half the armament of the world.

And then in the year 2050 the blow fell. Lieutenant-Commander Orthis, after twenty-four years upon the moon, returned to earth with one hundred thousand Kalkars and a thousand Va-gas. In a thousand great ships they came bearing arms and ammunition and strange, new engines of destruction fashioned by the brilliant mind of the arch villain of the universe.

No one but Orthis could have done it. No one but Orthis would have done it. It had been he who had perfected the engines that had made the Barsoom possible. After he had become the dominant force among the Kalkars of the moon he had aroused their imaginations with tales of the great, rich world lying ready and unarmed within easy striking distance of them. It had been an easy thing to enlist their labor in the building of the ships and the manufacture of the countless accessories necessary to the successful accomplishment of the great adventure.

The moon furnished all the needed materials, the Kalkars furnished the labor and Orthis the knowledge, the brains and the leadership. Ten years had been devoted to the spreading of his propaganda and the winning over of the Thinkers, and then fourteen years were required to build and outfit the fleet.

Five days before they arrived astronomers detected the fleet as minute specks upon the eyepieces of their telescopes. There was much speculation, but it was Julian 5th alone who guessed the truth. He warned the governments at London and Washington, but though he was then in command of the International Peace Fleet his appeals were treated with levity and ridicule. He knew Orthis and so he knew that it was easily within the man's ability to construct a fleet, and he also knew that only for one purpose would Orthis return to Earth with so great a number of ships. It meant war, and the earth had nothing but a handful of cruisers wherewith to defend herself—there were not available in the world twenty-five thousand organized fighting men, nor equipment for more than half again that number.

The inevitable occurred. Orthis seized London and Washington simultaneously. His well armed forces met with practically no resistance. There could be no resistance for there was nothing wherewith to resist. It was a criminal offense to possess firearms. Even edged weapons with blades over six inches long were barred by law. Military training, except for the chosen few of the International Peace Fleet, had been banned for years. And against this pitiable state of disarmament and unpreparedness was brought a force of a hundred thousand well armed, seasoned warriors with engines of destruction that were unknown to earth men. A description of one alone will suffice to explain the utter hopelessness of the cause of the earth men.

This instrument, of which the invaders brought but one, was mounted upon the deck of their flag ship and operated by Orthis in person. It was an invention of his own which no Kalkar understood or could operate. Briefly, it was a device for the generation of radio activity at any desired vibratory rate and for the directing of the resultant emanations upon any given object within its effective range. We do not know what Orthis called it, but the earth men of that day knew it was an electronic rifle.

It was quite evidently a recent invention and, therefore, in some respects crude, but be that as it may its effects were sufficiently deadly to permit Orthis to practically wipe out the entire International Peace Fleet in less than thirty days as rapidly as the various ships came within range of the electronic rifle. To the layman the visual effects induced by this weird weapon were appalling and nerve shattering. A mighty cruiser vibrant with life and power might fly majestically to engage the flagship of the Kalkars, when as by magic every aluminum part of the cruiser would vanish as mist before the sun, and as nearly ninety per cent of a peace fleet cruiser, including the hull, was constructed of aluminum, the result may be imagined—one moment there was a great ship forging through the air, her flags and pennants flying in the wind, her band playing, her officers and men at their quarters; the next a mass of engines, polished wood, cordage, flags and human beings hurtling earthward to extinction.

It was Julian 5th who discovered the secret of this deadly weapon and that it accomplished its destruction by projecting upon the ships of the Peace Fleet the vibratory rate of radio-activity identical with that of aluminum, with the result that, thus excited, the electrons of the attacked substance increased their own vibratory rate to a point that they became dissipated again into their elemental and invisible state—in other words aluminum was transmuted into something else that was as invisible and intangible as ether. Perhaps it was ether.

Assured of the correctness of his theory, Julian 5th withdrew in his own flagship to a remote part of the world, taking with him the few remaining cruisers of the fleet. Orthis searched for them for months, but it was not until the close of the year 2050 that the two fleets met again and for the last time. Julian 5th had, by this time, perfected the plan for which he had gone into hiding, and he now faced the Kalkar fleet and his old enemy, Orthis, with some assurance of success. His flagship moved at the head of the short column that contained the remaining hope of a world and Julian 5th stood upon her deck beside a small and innocent looking box mounted upon a stout tripod.

Orthis moved to meet him—he would destroy the ships one by one as he approached them. He gloated at the easy victory that lay before him. He directed the electronic rifle at the flagship of his enemy and touched a button. Suddenly his brows knitted. What was this? He examined the rifle. He held a piece of aluminum before its muzzle and saw the metal disappear. The mechanism was operating, but the ships of the enemy did not disappear. Then he guessed the truth, for his own ship was now but a short distance from that of Julian 5th and he could see that the hull of the latter was entirely coated with a grayish substance that he sensed at once for what it was—an insulating material that rendered the aluminum parts of the enemy's fleet immune from the invisible fire of his rifle.

Orthis's scowl changed to a grim smile. He turned two dials upon a control box connected with the weapon and again pressed the button. Instantly the bronze propellers of the earth man's flagship vanished in thin air together with numerous fittings and parts above decks. Similarly went the exposed bronze parts of the balance of the International Peace Fleet, leaving a squadron of drifting derelicts at the mercy of the foe.

Julian 5th's flagship was at that time but a few fathoms from that of Orthis. The two men could plainly see each other's features. Orthis's expression was savage and gloating, that of Julian 5th sober and dignified.

"You thought to beat me, then!" jeered Orthis. "God, but I have waited and labored and sweated for this day. I have wrecked a world to best you, Julian 5th. To best you and to kill you, but to let you know first that I am going to kill you—to kill you in such a way as man was never before killed, as no other brain than mine could conceive of killing. You insulated your aluminum parts thinking thus to thwart me, but you did not know—your feeble intellect could not know—that as easily as I destroyed aluminum I can, by the simplest of adjustments, attune this weapon to destroy any one of a hundred different substances and among them human flesh or human bone.

"That is what I am going to do now, Julian 5th. First I am going to dissipate the bony structure of your frame. It will be done painlessly—it may not even result in instant death, and I am hoping that it will not. For I want you to know the power of a real intellect—the intellect from which you stole the fruits of its efforts for a lifetime; but not again, Julian 5th, for today you die—first your bones, then your flesh, and after you, your men and after them your spawn, the son that the woman I loved bore you; but she—she shall belong to me! Take that memory to hell with you!" and he turned toward the dials beside his lethal weapon.

But Julian 5th placed a hand upon the little box resting upon the strong tripod before him, and he, it was, who touched a button before Orthis had touched his. Instantly the electronic rifle vanished beneath the very eyes of Orthis and at the same time the two ships touched and Julian 5th had leaped the rail to the enemy deck and was running toward his arch enemy.

Orthis stood gazing, horrified, at the spot where the greatest invention of his giant intellect had stood but an instant before, and then he looked up at Julian 5th approaching him and cried out horribly.

"Stop!" he screamed. "Always all our lives you have robbed me of the fruits of my efforts. Somehow you have stolen the secret of this, my greatest invention, and now you have destroyed it. May God in Heaven—"

"Yes," cried Julian 5th, "and I am going to destroy you, unless you surrender to me with all your force."

"Never!" almost screamed the man, who seemed veritably demented, so hideous was his rage. "Never! This is the end, Julian 5th, for both of us," and even as he uttered the last word he threw a lever mounted upon a control board before him. There was a terrific explosion and both ships, bursting into flame, plunged meteor-like into the ocean beneath.

Thus went Julian 5th and Orthis to their deaths, carrying with them the secret of the terrible destructive force that the latter had brought with him from the moon; but the earth was already undone. It lay helpless before its conquerors. What the outcome might have been had Orthis lived can only remain conjecture. Possibly he would have brought order out of the chaos he had created and instituted a reign of reason. Earth men would at least have had the advantage of his wonderful intellect and his power to rule the ignorant Kalkars that he had transported from the moon.

There might even have been some hope had the earth men banded together against the common enemy, but this they did not do. Elements which had been discontented with this or that phase of government joined issues with the invaders. The lazy, the inefficient, the defective, who ever place the blame for their failures upon the shoulders of the successful, swarmed to the banners of the Kalkars, in whom they sensed kindred souls.

Political factions, labor and capital saw, or thought they saw, an opportunity for advantage to themselves in one way or another that was inimical to the interests of the others. The Kalkar fleets returned to the moon for more Kalkars until it was estimated that seven millions of them were being transported to earth each year.

Julian 6th, with Nah-ee-lah, his mother, lived, as did Or-tis, the son of Orthis and a Kalkar woman, but my story is not to be of them, but of Julian 9th, who was born just a century after the birth of Julian 5th.

Julian 9th will tell his own story.

I WAS born in the Teivos of Chicago on January 1st, 2100, to Julian 8th and Elizabeth James. My father and mother were not married as marriages had long since become illegal. I was called Julian 9th. My parents were of the rapidly diminishing intellectual class and could both read and write. This learning they imparted to me, although it was very useless learning—it was their religion. Printing was a lost art and the last of the public libraries had been destroyed almost a hundred years before I reached maturity, so there was little or nothing to read, while to have a book in one's possession was to brand one as one of the hated intellectuals, arousing the scorn and derision of the Kalkar rabble and the suspicion and persecution of the lunar authorities who ruled.

The first twenty years of my life were uneventful. As a boy I played among the crumbling ruins of what must once have been a magnificent city. Pillaged, looted and burned half a hundred times Chicago still reared the skeletons of some mighty edifices above the ashes of her former greatness. As a youth I regretted the departed romance of the long gone days of my fore-fathers when the earth men still retained sufficient strength to battle for existence. I deplored the quiet stagnation of my own time with only an occasional murder to break the monotony of our bleak existence. Even the Kalkar Guard stationed on the shore of the great lake seldom harassed us, unless there came an urgent call from higher authorities for an additional tax collection, for we fed them well and they had the pick of our women and young girls—almost, but not quite as you shall see.

The commander of the guard had been stationed here for years and we considered ourselves very fortunate in that he was too lazy and indolent to be cruel or oppressive. His tax collectors were always with us on market days; but they did not exact so much that we had nothing left for ourselves as refugees from Milwaukee told us was the case there.

I recall one poor devil from Milwaukee who staggered into our market place of a Saturday. He was nothing more than a bag of bones and he told us that fully ten thousand people had died of starvation the preceding month in his Teivos. The word Teivos is applied impartially to a district and to the administrative body that maladministers its affairs. No one knows what the word really means, though my mother has told me that her grandfather said that it came from another world, the moon, like Kash Guard, which also means nothing in particular—one soldier is a Kash Guard, ten thousand soldiers are a Kash Guard. If a man comes with a piece of paper upon which something is written that you are not supposed to be able to read and kills your grandmother or carries off your sister you say: "The Kash Guard did it."

That was one of the many inconsistencies of our form of government that aroused my indignation even in youth—I refer to the fact that the Twenty-Four issued written proclamations and commands to a people it did not allow to learn to read and write, I said, I believe, that printing was a lost art. This is not quite true except as it refers to the mass of the people, for the Twenty-Four still maintained a printing department, where it issued money and manifestos. The money was used in lieu of taxation—that is when we had been so over-burdened by taxation that murmurings were heard even among the Kalkar class the authorities would send agents among us to buy our wares, paying us with money that had no value and which we could not use except to kindle our fires.

Taxes could not be paid in money as the Twenty-Four would only accept gold and silver, or produce and manufactures, and as all the gold and silver had disappeared from circulation while my father was in his teens we had to pay with what we raised or manufactured.

Three Saturdays a month the tax collectors were in the market places appraising our wares and on the last Saturday they collected one per cent of all we had bought or sold during the month. Nothing had any fixed value—today you might haggle half an hour in trading a pint of beans for a goat skin and next week if you wanted beans the chances were more than excellent that you would have to give four or five goat skins for a pint, and the tax collectors took advantage of that—they appraised on the basis of the highest market values for the month.

My father had a few long haired goats—they were called Montana goats, but he said they really were Angoras, and mother used to make cloth from their fleece. With the cloth, the milk and the flesh from our goats we lived very well, having also a small vegetable garden beside our house; but there were some necessities that we must purchase in the market place. It was against the law to barter in private, as the tax collectors would then have known nothing about a man's income. Well, one winter my mother was ill and we were in sore need of coal to heat the room in which she lay, so father went to the commander of the Kash Guard and asked permission to purchase some coal before market day. A soldier was sent with him to Hoffmeyer, the agent of the Kalkar, Pthav, who had the coal concession for our district—the Kalkars have everything—and when Hoffmeyer discovered how badly we needed coal he said that for five milk goats father could have half his weight in coal.

My father protested, but it was of no avail and as he knew how badly my mother needed heat he took the five goats to Hoffmeyer and brought back the coal. On the following market day he paid one goat for a sack of beans equal to his weight and when the tax collector came for his tithe he said to father: "You paid five goats for half your weight in beans, and as everyone knows that beans are worth twenty times as much as coal, the coal you bought must be worth one hundred goats by now, and as beans are worth twenty times as much as coal and you have twice as much beans as coal your beans are now worth two hundred goats, which makes your trades for this month amount to three hundred goats. Bring me, therefore, three of your best goats."

He was a new tax collector—the old one would not have done such a thing; but it was about that time that everything began to change. Father said he would not have thought that things could be much worse; but he found out differently later. The change commenced in 2017, right after Jarth became Jemadar of the United Teivos of America. Of course, it did not all happen at once. Washington is a long way from Chicago and there is no continuous railroad between them. The Twenty-Four keeps up a few disconnected lines; but it is hard to operate them as there are no longer any trained mechanics to maintain them. It never takes less than a week to travel from Washington to Gary, the western terminus.

Father said that most of the railways were destroyed during the wars after the Kalkars overran the country and that as workmen were then permitted to labor only four hours a day, when they felt like it, and even then most of them were busy making new laws so much of the time that they had no chance to work, there was not enough labor to operate or maintain the roads that were left, but that was not the worst of it. Practically all the men who understood the technical details of operation and maintenance, of engineering and mechanics belonged to the more intelligent class of earthmen and were, consequently, immediately thrown out of employment and later killed.

For seventy-five years there had been no new locomotives built and but few repairs made on those in existence. The Twenty-Four had sought to delay the inevitable by operating a few trains only for their own requirements—for government officials and troops; but it could now be but a question of a short time before railroad operation must cease—forever. It didn't mean much to me as I had never ridden on a train—never even seen one, in fact, other than the rusted remnants, twisted and tortured by fire, that lay scattered about various localities of our city; but father and mother considered it a calamity—the passing of the last link between the old civilization and the new barbarism.

Airships, automobiles, steamships, and even the telephone had gone before their time; but they had heard their fathers tell of these and other wonders. The telegraph was still in operation, though the service was poor and there were only a few lines between Chicago and the Atlantic seaboard. To the west of us was neither railroad nor telegraph. I saw a man when I was about ten years old who had come on horseback from a Teivos in Missouri. He started out with forty others to get in touch with the east and learn what had transpired there in the past fifty years; but between bandits and Kash Guards all had been killed but himself during the long and adventurous journey.

I shall never forget how I hung about picking up every scrap of the exciting narrative that fell from his lips nor how my imagination worked overtime for many weeks thereafter as I tried to picture myself the hero of similar adventures in the mysterious and unknown west. He told us that conditions were pretty bad in all the country he had passed through; but that in the agricultural districts living was easier because the Kash Guard came less often and the people could gain a fair living from the land. He thought our conditions were worse than those in Missouri and he would not remain, preferring to face the dangers of the return trip rather than live so comparatively close to the seat of the Twenty-Four.

Father was very angry when he came home from market after the new tax collector had levied a tax of three goats on him. Mother was up again and the cold snap had departed leaving the mildness of spring in the late March air. The ice had gone off the river on the banks of which we lived and I was already looking forward to my first swim of the year. The goat skins were drawn back from the windows of our little home and the fresh, sun-laden air was blowing through our three rooms.

"Bad times are coming, Elizabeth," said father, after he had told her of the injustice. "They have been bad enough in the past; but now that the swine have put the king of swine in as Jemadar—"

"S-s-sh!" cautioned my mother, nodding her head toward the open window.

Father remained silent, listening. We heard footsteps passing around the house toward the front and a moment later the form of a man darkened the door. Father breathed a sigh of relief.

"Ah!" he exclaimed, "it is only our good brother Johansen. Come in, Brother Peter and tell us the news."

"And there is news enough," exclaimed the visitor. "The old commandant has been replaced by a new one, a fellow by the name of Or-tis—one of Jarth's cronies. What do you think of that?"

Brother Peter was standing between father and mother with his back toward the latter, so he did not see mother place her finger quickly to her lips in a sign to father to guard his speech. I saw a slight frown cross my father's brow, as though he resented my mother's warning; but when he spoke his words were such as those of our class have learned through suffering are the safest.

"It is not for me to think," he said, "or to question in any way what the Twenty-Four does."

"Nor for me," spoke Johansen quickly; "but among friends—a man cannot help but think and sometimes it is good to speak your mind—eh?"

Father shrugged his shoulders and turned away. I could see that he was boiling over with a desire to unburden himself of some of his loathing for the degraded beasts that Fate had placed in power nearly a century before. His childhood had still been close enough to the glorious past of his country's proudest days to have been impressed through the tales of his elders with a poignant realization of all that had been lost and of how it had been lost. This he and mother had tried to impart to me as others of the dying intellectuals attempted to nurse the spark of a waning culture in the breasts of their offspring against that always hoped for, yet seemingly hopeless, day when the world should start to emerge from the slough of slime and ignorance into which the cruelties of the Kalkars had dragged it.

"Now, Brother Peter," said father, at last, "I must go and take my three goats to the tax collector, or he will charge me another one for a fine." I saw that he tried to speak naturally; but he could not keep the bitterness out of his voice.

Peter pricked up his ears. "Yes," he said, "I had heard of that piece of business. This new tax collector was laughing about it to Hoffmeyer. He thinks it a fine joke and Hoffmeyer says that now that you got the coal for so much less than it was worth he is going before the Twenty-Four and ask that you be compelled to pay him the other ninety-five goats that the tax collector says the coal is really worth."

"Oh!" exclaimed mother, "they would not really do such a wicked thing—I am sure they would not."

Peter shrugged. "Perhaps they only joked," he said; "these Kalkars are great jokers."

"Yes," said father, "they are great jokers; but some day I shall have my little joke," and he walked out toward the pens where the goats were kept when not on pasture.

Mother looked after him with a troubled light in her eyes and I saw her shoot a quick glance at Peter, who presently followed father from the house and went his way.

Father and I took the goats to the tax collector. He was a small man with a mass of red hair, a thin nose and two small, close-set eyes. His name was Soor. As soon as he saw father he commenced to fume.

"What is your name, man?" he demanded insolently.

"Julian 8th," replied father. "Here are the three goats in payment of my income tax for this month—shall I put them in the pen?"

"What did you say your name is?" snapped the fellow.

"Julian 8th," father repeated.

"Julian 8th!" shouted Soor. "'Julian 8th!' I suppose you are too fine a gentleman to be brother to such as me, eh?"

"Brother Julian 8th," said father sullenly.

"Go put your goats in the pen and hereafter remember that all men are brothers who are good citizens and loyal to our great Jemadar."

When father had put the goats away we started for home; but as we were passing Soor he shouted: "Well?"

Father turned a questioning look toward him.

"Well?" repeated the man.

"I do not understand," said father; "have I not done all that the law requires?"

"What's the matter with you pigs out here?" Soor fairly screamed. "Back in the eastern Teivos a tax collector doesn't have to starve to death on his miserable pay—his people bring him little presents."

"Very well," said father quietly, "I will bring you something next time I come to market."

"See that you do," snapped Soor.

Father did not speak all the way home, nor did he say a word until after we had finished our dinner of cheese, goat's milk and corn cakes. I was so angry that I could scarce contain myself; but I had been brought up in an atmosphere of repression and terrorism that early taught me to keep a still tongue in my head.

When father had finished his meal he rose suddenly—so suddenly that his chair flew across the room to the opposite wall—and squaring his shoulders he struck his chest a terrible blow.

"Coward! Dog!" he cried. "My God! I cannot stand it. I shall go mad if I must submit longer to such humiliation. I am no longer a man. There are no men! We are worms that the swine grind into the earth with their polluted hoofs. And I dared say nothing. I stood there while that offspring of generations of menials and servants insulted me and spat upon me and I dared say nothing but meekly to propitiate him. It is disgusting.

"In a few generations they have sapped the manhood from American men. My ancestors fought at Bunker Hill, at Gettysburg, at San Juan, at Chateau Thierry. And I? I bend the knee to every degraded creature that wears the authority of the beasts at Washington—and not one of them is an American—scarce one of them an earth man. To the scum of the moon I bow my head—I who am one of the few survivors of the most powerful people the world ever knew."

"Julian!" cried my mother, "be careful, dear. Some one may be listening." I could see her tremble.

"And you are an American woman!" he growled.

"Julian, don't!" she pleaded. "It is not on my account—you know that it is not—but for you and our boy. I do not care what becomes of me; but I cannot see you torn from us as we have seen others taken from their families, who dared speak their minds."

"I know, dear heart," he said after a brief silence. "I know—it is the way with each of us. I dare not on your account and Julian's, you dare not on ours, and so it goes. Ah, if there were only more of us. If I could but find a thousand men who dared!"

"S-s-sh!" cautioned mother. "There are so many spies. One never knows. That is why I cautioned you when Brother Peter was here today. One never knows."

"You suspect Peter?" asked father.

"I know nothing," replied mother; "I am afraid of every one. It is a frightful existence and though I have lived it thus all my life, and my mother before me and her mother before that, I never became hardened to it."

"The American spirit has been bent but not broken," said father. "Let us hope that it will never break."

"If we have the hearts to suffer always it will not break," said mother, "but it is hard, so hard—when one even hates to bring a child into the world," and she glanced at me, "because of the misery and suffering to which it is doomed for life. I yearned for children, always; but I feared to have them—mostly I feared that they might be girls. To be a girl in this world today—Oh, it is frightful!"

After supper father and I went out and milked the goats and saw that the sheds were secured for the night against the dogs. It seemed as though they became more numerous and more bold each year. They ran in packs where there were only individuals when I was a little boy and it was scarce safe for a grown man to travel an unfrequented locality at night. We were not permitted to have firearms in our possession, nor even bows and arrows, so we could not exterminate them and they seem to realize our weakness, coming close in among the houses and pens at night.

They were large brutes—fearless and powerful. There was one pack more formidable than the others which father said appeared to carry a strong strain of collie and airedale blood—the members of this pack were large, cunning and ferocious and were becoming a terror to the city—we called them the Hellhounds.

AFTER we returned to the house with the milk Jim Thompson and his woman, Mollie Sheehan, came over. They lived up the river about half a mile, on the next farm, and were our best friends. They were the only people that father and mother really trusted, so when we were all together alone we spoke our minds very freely. It seemed strange to me, even as a boy, that such, big strong men as father and Jim should be afraid to express their real views to any one, and though I was born and reared in an atmosphere of suspicion and terror I could never quite reconcile myself to the attitude of servility and cowardice which marked us all.

And yet I knew that my father was no coward. He was a fine-looking man, too—tall and wonderfully muscled—and I have seen him fight with men and with dogs and once he defended mother against a Kash Guard and with his bare hands he killed the armed soldier. He lies in the center of the goat pen now, his rifle, bayonet and ammunition wrapped in many thicknesses of oiled cloth beside him. We left no trace and were never even suspected; but we know where there is a rifle, a bayonet and ammunition.

Jim had had trouble with Soor, the new tax collector, too, and was very angry. Jim was a big man and, like father, was always smooth shaven as were nearly all Americans, as we called those whose people had lived here long before the Great War. The others—the true Kalkars—grew no beards. Their ancestors had come from the moon many years before. They had come in strange ships year after year, but finally, one by one, their ships had been lost and as none of them knew how to build others or the engines that operated them the time came when no more Kalkars could come from the moon to earth.

That was good for us, but it came too late, for the Kalkars already here bred like flies in a shady stable. The pure Kalkars were the worst, but there were millions of half-breeds and they were bad, too, and I think they really hated us pure bred earth men worse than the true Kalkars, or moon men, did.

Jim was terribly mad. He said that he couldn't stand it much longer—that he would rather be dead than live in such an awful world; but I was accustomed to such talk—I had heard it since infancy. Life was a hard thing—just work, work, work, for a scant existence over and above the income tax. No pleasures—few conveniences or comforts; absolutely no luxuries—and, worst of all, no hope. It was seldom that any one smiled—any one in our class—and the grown-ups never laughed. As children we laughed—a little; not much. It is hard to kill the spirit of childhood; but the brotherhood of man had almost done it.

"It's your own fault, Jim," said father. He was always blaming our troubles on Jim, for Jim's people had been American workmen before the Great War—mechanics and skilled artisans in various trades. "Your people never took a stand against the invaders. They flirted with the new theory of brotherhood the Kalkars brought with them from the moon.

"They listened to the emissaries of the malcontents and, afterward, when Kalkars sent their disciples among us they ‘first endured, then pitied, then embraced.' They had the numbers and the power to combat successfully the wave of insanity that started with the lunar catastrophe and overran the world—they could have kept it out of America; but they didn't—instead they listened to false prophets and placed their great strength in the hands of the corrupt leaders."

"And how about your class?" countered Jim, "too rich and lazy and indifferent even to vote. They tried to grind us down while they waxed fat off of our labor."

"The ancient sophistry!" snapped father. "There was never a more prosperous or independent class of human beings in the world than the American laboring man of the twentieth century."

"You talk about us! We were the first to fight it—my people fought and bled and died to keep Old Glory above the capitol at Washington; but we were too few and now the Kash flag of the Kalkars floats in its place and for nearly a century it had been a crime punishable by death to have the Stars and Stripes in your possession."

He walked quickly across the room to the fireplace and removed a stone above the rough, wooden mantel. Reaching his hand into the aperture behind he turned toward us.

"But cowed and degraded as I have become," he cried, "thank God I still have a spark of manhood left—I have had the strength to defy them as my fathers defied them—I have kept this that has been handed down to me—kept it for my son to hand down to his son—and I have taught him to die for it as his forefathers died for it and as I would die for it, gladly."

He drew forth a small bundle of fabric and holding the upper corners between the fingers of his two hands he let it unfold before us—an oblong cloth of alternate red and white striped with a blue square in one corner, upon which were sewn many little white stars.

Jim and Mollie and mother rose to their feet and I saw mother cast an apprehensive glance toward the doorway. For a moment they stood thus in silence, looking with wide eyes upon the thing that father held and then Jim walked slowly toward it and, kneeling, took the edge of it in his great, horny fingers and pressed it to his lips and the candle upon the rough table, sputtering in the spring wind that waved the the goat skin at the window, cast its feeble rays upon them.

"It is the Flag, my son," said father to me. "It is Old Glory—the flag of your fathers—the flag that made the world a decent place to live in. It is death to possess it; but when I am gone take it and guard it as our family has guarded it since the regiment that carried it came back from the Argonne."

I felt tears filling my eyes—why, I could not have told them—and I turned away to hide them—turned toward the window and there, beyond the waving goat skin, I saw a face in the outer darkness. I have always been quick of thought and of action; but I never thought or moved more quickly in my life than I did in the instant following my discovery of the face in the window. With a single movement I swept the candle from the table, plunging the room into utter darkness, and leaping to my father's side I tore the Flag from his hands and thrust it back into the aperture above the mantel. The stone lay upon the mantel itself, nor did it take me but a moment to grope for it and find it in the dark—an instant more and it was replaced in its niche.

So ingrained were apprehension and suspicion in the human mind that the four in the room with me sensed intuitively something of the cause of my act and when I had hunted for the candle, found it and relighted it they were standing, tense and motionless where I had last seen them. They did not ask me a question. Father was the first to speak.

"You were very careless and clumsy, Julian," he said. "If you wanted the candle why did you not pick it up carefully instead of rushing at it so? But that is always your way—you are constantly knocking things over."

He raised his voice a trifle as he spoke; but it was a lame attempt at deception and he knew it, as did we. If the man who owned the face in the dark heard his words he must have known it as well.

As soon as I had relighted the candle I went into the kitchen and out the back door and then, keeping close in the black shadow of the house, I crept around toward the front, for I wanted to learn, if I could, who it was who had looked in upon that scene of high treason. The night was moonless but clear, and I could see quite a distance in every direction, as our house stood in a fair size clearing close to the river. Southeast of us the path wound upward across the approach to an ancient bridge, long since destroyed by raging mobs or rotting away—I do not know which—and presently I saw the figure of a man silhouetted against the starlit sky as he topped the approach. The man carried a laden sack upon his back. This fact was, to some extent, reassuring as it suggested that the eavesdropper was himself upon some illegal mission and that he could ill afford to be too particular of the actions of others. I have seen many men carrying sacks and bundles at night—I have carried them myself. It is the only way, often, in which a man may save enough from the tax collector on which to live and support his family.

This nocturnal traffic is common enough and under our old tax collector and the indolent commandant of former times not so hazardous as it might seem when one realizes that it is punishable by imprisonment for ten years at hard labor in the coal mines and, in aggravated cases, by death. The aggravated cases are those in which a man is discovered trading something by night that the tax collector or the commandant had wanted for himself.

I did not follow the man, being sure that he was one of our own class, but turned back toward the house where I found the four talking in low whispers, nor did any of us raise his voice again that evening.

Father and Jim were talking, as they usually did, of the West. They seemed to feel that somewhere, far away toward the setting sun, there must be a little corner of America where men could live in peace and freedom—where there were no Kash Guards, tax collectors or Kalkars.

It must have been three quarters of an hour later, as Jim and Mollie were preparing to leave, that there came a knock upon the door which immediately swung open before an invitation to enter could be given. We looked up to see Peter Johansen smiling at us. I never liked Peter. He was a long, lanky man who smiled with his mouth; but never with his eyes. I didn't like the way he used to look at mother when he thought no one was observing him, nor his habit of changing women every year or two—that was too much like the Kalkars. I always felt toward Peter as I had as a child when, barefooted, I stepped unknowingly upon a snake in the deep grass.

Father greeted the newcomer with a pleasant "Welcome, Brother Johansen;" but Jim only nodded his head and scowled, for Peter had a habit of looking at Mollie as he did at mother, and both women were beautiful. I think I never saw a more beautiful woman than my mother and as I grew older and learned more of men and the world I marveled that father had been able to keep her and, too, I understood why she never went abroad; but stayed always closely about the house and farm. I never knew her to go to the market place as did most of the other women. But I was twenty now and worldly wise.

"What brings you out so late, Brother Johansen?" I asked. We always used the prescribed "Brother" to those of whom we were not sure. I hate the word—to me a brother meant an enemy as it did to all our class and I guess to every class—even the Kalkars.

"I followed a stray pig," replied Peter to my question. "He went in that direction," and he waved a hand toward the market place. As he did so something tumbled from beneath his coat—something that his arm had held there. It was an empty sack. Immediately I knew who it was owned the face in the dark beyond our goatskin hanging. Peter snatched the sack from the floor in ill-concealed confusion and then I saw the expression of his cunning face change as he held it toward father.

"Is this yours, Brother Julian?" he asked. "I found it just before your door and thought that I would stop and ask."

"No," said I, not waiting for father to speak, "it is not ours—it must belong to the man whom I saw carrying it, full, a short time since. He went by the path beside the old bridge." I looked straight into Peter's eyes. He flushed and then went white.

"I did not see him," he said presently; "but if the sack is not yours I will keep it—at least it is not high treason to have it in my possession." Then, without another word, he turned and left the house.

We all knew then that Peter had seen the episode of the flag. Father said that we need not fear, that Peter was all right; but Jim thought differently and so did Mollie and mother, I agreed with them. I did not like Peter. Jim and Mollie went home shortly after Peter left and we prepared for bed. Mother and Father occupied the one bedroom. I slept on some goat skins in the big room we called the living room. The other room was a kitchen. We ate there also.

Mother had always made me take off my clothes and put on a mohair garment for sleeping. The other young men I knew slept in the same clothes they wore during the day; but mother was particular about this and insisted that I have my sleeping garments and also that I bathed often—once a week in the winter. In the summer I was in the river so much that I had a bath once or twice a day. Father was also particular about his personal cleanliness. The Kalkars were very different.

My underclothing was of fine mohair, in winter. In summer I wore none: I had a heavy mohair shirt and breeches, tight at waist and knees and baggy between, a goatskin tunic and boots of goatskin. I do not know what we would have done without the goats—they furnished us food and raiment. The boots were loose and fastened just above the calf of the leg with a strap—to keep them from falling down. I wore nothing on my head, summer or winter; but my hair was heavy. I wore it brushed straight back, always, and cut off square behind just below my ears. To keep it from getting in my eyes I always tied a goatskin thong about my head.

I had just slipped off my tunic when I heard the baying of the Hellhounds close by. I thought they might be getting into the goat pen, so I waited a moment, listening and then I heard a scream—the scream of a woman in terror. It sounded down by the river near the goat pens, and mingled with it was the vicious growling and barking of the Hellhounds. I did not wait to listen longer, but seized my knife and a long staff. We were permitted to have no edged weapon with a blade over six inches long. Such as it was, it was the best weapon I had and much better than none.

I ran out the front door, which was closest, and turned toward the pens in the direction of the Hellhounds' deep growling and the screams of the woman.

As I neared the pens and my eyes became accustomed to the outer darkness I made out what appeared to be a human figure resting partially upon the top of one of the sheds that formed a portion of the pen wall. The legs and lower body dangled over the edge of the roof and I could see three or four Hellhounds leaping for it, while another, that had evidently gotten a hold, was hanging to one leg and attempting to drag the figure down.

As I ran forward I shouted at the beasts and those that were leaping for the figure stopped and turned toward me. I knew something of the temper of these animals and that I might expect them to charge, for they were quite fearless of man ordinarily; but I ran forward toward them so swiftly and with such determination that they turned growling and ran off.

The one that had hold of the figure succeeded in dragging it to earth just before I reached them and then it discovered me and turned, standing over its prey, with wide jaws and terrific fangs menacing me. It was a huge beast, almost as large as a full grown goat, and easily a match for several men as poorly armed as I. Under ordinary circumstances I should have given it plenty of room; but what was I to do when the life of a woman was at stake?

I was an American, not a Kalkar—those swine would throw a woman to the Hellhounds to save their own skins—and I had been brought up to revere woman in a world that considered her on a par with the cow, the nanny and the sow, only less valuable since the latter were not the common property of the state.

I knew then that death stood very near as I faced that frightful beast and from the corner of an eye I could see its mates creeping closer. There was no time to think, even, and so I rushed in upon the Hellhound with my staff and blade. As I did so I saw the wide and terrified eyes of a young girl looking up at me from beneath the beast of prey. I had not thought to desert her to her fate before; but after that single glance I could not have done so had a thousand deaths confronted me.

As I was almost upon the beast it sprang for my throat, rising high upon its hind feet and leaping straight as an arrow. My staff was useless and so I dropped it, meeting the charge with my knife and a bare hand. By luck the fingers of my left hand found the creature's throat at the first clutch; but the impact of his body against mine hurled me to the ground beneath him and there, growling and struggling, he sought to close those snapping fangs upon me. Holding his jaws at arm's length I struck at his breast with my blade, nor did I miss him once. The pain of the wounds turned him crazy and yet, to my utter surprise found I still could hold him and not that alone; but that I could also struggle to my knees and then to my feet—still holding him at arm's length in my left hand.

I had always known that I was muscular; but until that moment I had never dreamed of the great strength that Nature had given me, for never before had I had occasion to exert the full measure of my powerful thews. It was like a revelation from above and of a sudden I found myself smiling and in the instant a miracle occurred—all fear of these hideous beasts dissolved from my brain like thin air and with it fear of man as well. I, who had been brought out of a womb of fear into a world of terror, who had been suckled and nurtured upon apprehension and timidity—I, Julian 9th, at the age of twenty years, became in the fraction of a second utterly fearless of man or beast. It was the knowledge of my great power that did it—that and, perhaps, those two liquid eyes that I knew to be watching me.

The other hounds were closing in upon me when the creature in my grasp went suddenly limp. My blade must have found its heart. And then the others charged and I saw the girl upon her feet beside me, my staff in her hands, ready to battle with them.

"To the roof!" I shouted to her; but she did not heed. Instead she stood her ground, striking a vicious blow at the leader as he came within range.

Swinging the dead beast above my head I hurled the carcass at the others so that they scattered and retreated again and then I turned to the girl and without more parley lifted her in my arms and tossed her lightly to the roof of the goat shed. I could easily have followed to her side and safety had not something filled my brain with an effect similar to that which I imagined must be produced by the vile concoction brewed by the Kalkars and which they drank to excess, while it would have meant imprisonment for us to be apprehended with it in our possession. At least, I know that I felt a sudden exhilaration—a strange desire to accomplish wonders before the eyes of this stranger, and so I turned upon the four remaining hellhounds who had now bunched to renew the attack and without waiting for them I rushed toward them.

They did not flee; but stood their ground, growling hideously, their hair bristling upon their necks and along their spines, their great fangs bared and slavering; but among them I tore and by the very impetuosity of my attack I overthrew them. The first sprang to meet me and him I seized by the neck and clamping his body between my knees I twisted his head entirely around, until I heard the vertebrae snap. The other three were upon me then, leaping and tearing; but I felt no fear. One by one I took them in my mighty hands and lifting them high above my head hurled them violently from me. Two only returned to the attack and these I vanquished with my bare hands disdaining to use my blade upon such carrion.

It was then that I saw a man running toward me from up the river and another from our house. The first was Jim, who had heard commotion and the girl's screams and the other was my father. Both had seen the last part of the battle and neither could believe that it was I, Julian, who had done this thing. Father was very proud of me and Jim was, too, for he had always said that having no son of his own father must share me with him.

And then I turned toward the girl who had slipped from the roof and was approaching us. She moved with the same graceful dignity that was mother's—not at all like the clumsy clods that belonged to the Kalkars, and she came straight to me and laid a hand upon my arm.

"Thank, you!" she said; "and God bless you. Only a very brave and powerful man could have done what you have done."

And then, all of a sudden, I did not feel brave at all; but very weak and silly, for all I could do was finger my blade and look at the ground. It was father who spoke and the interruption helped to dispel my embarrassment.

"Who are you?" he asked, "and from where do you come? It is strange to find a young woman wandering about alone at night; but stranger still to hear one who dares invoke the forbidden deity."

I had not realized until then that she had used His name; but when I did recall it, I could not but glance apprehensively about to see if any others might be around who could have heard. Father and Jim I knew to be safe; for there was a common tie between our families that lay in the secret religious rites we held once each week. Since that hideous day that had befallen even before my father's birth—that day, which none dared mention above a whisper, when the clergy of every denomination, to the last man, had been murdered by order of the Twenty-Four, it had been a capital crime to worship God in any form whatsoever.

Some madman at Washington, filled, doubtless, with the fumes of the awful drink that made them more bestial even than Nature designed them, issued the frightful order on the ground that the church was attempting to usurp the functions of the state and that also the clergy were inciting the people to rebellion—nor do I doubt but that the latter was true. Too bad, indeed, that they were not given more time to bring their divine plan to fruition.

We took the girl to the house and when my mother saw her and how young and beautiful she was and took her in her arms, the child broke down and sobbed and clung to mother, nor could either speak for some time. In the light of the candle I saw that the stranger was of wondrous beauty. I have said that my mother was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen, and such is the truth; but this girl who had come so suddenly among us was the most beautiful girl.

She was about nineteen, delicately molded and yet without weakness. There were strength and vitality apparent in every move she made as well as in the expression of her face, her gestures and her manner of speech. She was girlish and at the same time filled one with an impression of great reserves of strength of mind and character. She was very brown, showing exposure to the sun, yet her skin was clear—almost translucent.

Her garb was similar to mine—the common attire of people of our class, both men and women. She wore the tunic and breeches and boots just as mother and Mollie and the rest of us did; but somehow there was a difference—I had never before realized what a really beautiful costume it was. The band about her forehead was wider than was generally worn and upon it were sewn numerous tiny shells, set close together and forming a pattern. It was her only attempt at ornamentation; but even so it was quite noticeable in a world where women strove to make themselves plain rather than beautiful—some going even so far as to permanently disfigure their faces and those of their female offspring, while others, many, many others, killed the latter in infancy. Mollie had done so with two. No wonder that grown-ups never laughed and seldom smiled!

When the girl had quieted her sobs on mother's breast father renewed his questioning; but mother said to wait until morning, that the girl was tired and unstrung and needed sleep. Then came the question of where she was to sleep. Father said that he would sleep in the living room with me and that the stranger could sleep with mother; but Jim suggested that she come home with him as he and Mollie had three rooms, as did we, and no one to occupy his living room. And so it was arranged, although I would rather have had her remain with us.

At first she rather shrank from going, until mother told her that Jim and Mollie were good, kind-hearted people and that she would be as safe with them as with her own father and mother. At mention of her parents the tears came to her eyes and she turned impulsively toward my mother and kissed her, after which she told Jim that she was ready to accompany him.

She started to say goodbye to me and to thank me again; but, having found my tongue at last, I told her that I would go with them as far as Jim's house. This appeared to please her and so we set forth. Jim walked ahead and I followed with the girl, and on the way I discovered a very strange thing. Father had shown me a piece of iron once that pulled smaller bits of iron to it. He said that it was a magnet.

This slender, stranger girl was certainly no piece of iron, nor was I a smaller bit of anything; but nevertheless I could not keep away from her. I cannot explain it—however wide the way was I was always drawn over close to her, so that our arms touched and once our hands swung together and the strangest and most delicious thrill ran through me that I had ever experienced.

I used to think that Jim's house was a long way from ours—when I had to carry things over there as a boy; but that night it was far too close—just a step or two and we were there.

Mollie heard us coming and was at the door, full of questionings, and when she saw the girl and heard a part of our story she reached out and took the girl to her bosom, just as mother had. Before they took her in the stranger turned and held out her hand to me.

"Good night!" she said, "and thank you again, and, once more, may God, our Father, bless and preserve you."

And I heard Mollie murmur: "The Saints be praised!" and then they went in and the door closed and I turned homeward, treading on air.

THE next day I set out as usual to peddle goat's milk. We were permitted to trade in perishable things on other than market days, though we had to make a strict accounting of all such bartering. I usually left Mollie until the last as Jim had a deep, cold well on his place where I liked to quench my thirst after my morning trip; but that day Mollie got her milk fresh and first and early—about half an hour earlier than I was wont to start out.

When I knocked and she bid me enter she looked surprised at first, for just an instant, and then a strange expression came into her eyes—half amusement, half pity—and she rose and went into the kitchen for the milk jar. I saw her wipe the corners of her eyes with the back of one finger; but I did not understand why—not then.

The stranger girl had been in the kitchen helping Mollie and the latter must have told her I was there, for she came right in and greeted me. It was the first good look I had had of her, for candle light is not brilliant at best. If I had been enthralled the evening before there is no word in my limited vocabulary to express the effect she had on me by daylight. She—but it is useless. I cannot describe her!

It took Mollie a long time to find the milk jar—bless her!—though it seemed short enough to me, and while she was finding it the stranger girl and I were getting acquainted. First she asked after father and mother and then she asked our names. When I told her mine she repeated it several times. "Julian 9th," she said; "Julian 9th!" and then she smiled up at me. "It is a nice name, I like it."

"And what is your name?" I asked.

"Juana," she said—she pronounced it Whanna; "Juana St. John."

"I am glad," I said, "that you like my name; but I like yours better." It was a very foolish speech and it made me feel silly; but she did not seem to think it foolish, or if she did she was too nice to let me know it. I have known many girls; but mostly they were homely and stupid. The pretty girls were seldom allowed in the market place—that is, the pretty girls of our class. The Kalkars permitted their girls to go abroad, for they did not care who got them, as long as some one got them; but American fathers and mothers would rather slay their girls than send them to the market place, and the former often was done. The Kalkar girls, even those born of American mothers, were coarse and brutal in appearance—low-browed, vulgar, bovine. No stock can be improved, or even kept to its normal plane, unless high grade males are used.

This girl was so entirely different from any other that I had ever seen that I marvelled that such a glorious creature could exist. I wanted to know all about her. It seemed to me that in some way I had been robbed of my right for many years that she should have lived and breathed and talked and gone her way without my ever knowing it, or her. I wanted to make up for lost time and so I asked her many questions.

She told me that she had been born and raised in the Teivos just west of Chicago, which extended along the Desplaines River and embraced a considerable area of unpopulated country and scattered farms.

"My father's home is in a district called Oak Park," she said, "and our house was one of the few that remained from ancient times. It was of solid concrete and stood upon the corner of two roads—once it must have been a very beautiful place, and even time and war have been unable entirely to erase its charm. Three great poplar trees rose to the north of it beside the ruins of what my father said was once a place where motor cars were kept by the long dead owner. To the south of the house were many roses, growing wild and luxuriant, while the concrete walls, from which the plaster had fallen in great patches, were almost entirely concealed by the clinging ivy that reached to the very eaves.

"It was my home and so I loved it; but now it is lost to me forever. The Kash Guard and the tax collector came seldom—we were too far from the station and the market place, which lay southwest of us, on Salt Creek. But recently the new Jemadar, Jarth, appointed another commandant and a new tax collector. They did not like the station at Salt Creek and so they sought for a better location and after inspecting the district they chose Oak Park, and my father's home being the most comfortable and substantial, they ordered him to sell it to the Twenty-Four.

"You know what that means. They appraised it at a high figure—fifty thousand dollars it was, and paid him in paper money. There was nothing to do and so we prepared to move. Whenever they had come to look at the house my mother had hidden me in a little cubby-hole on the landing between the second and third floors, placing a pile of rubbish in front of me, but the day that we were leaving to take a place on the banks of the Desplaines, where father thought that we might live without being disturbed, the new commandant came unexpectedly and saw me.

"‘How old is the girl?' he asked my mother.

"‘Fifteen,' she replied sullenly.

"‘You lie, you sow!' he cried angrily; ‘she is eighteen if she is a day!'

"Father was standing there beside us and when the commandant spoke as he did to mother I saw father go very white and then, without a word, he hurled himself upon the swine and before the Kash Guard who accompanied him could prevent it, father had almost killed the commandant with his bare hands.

"You know what happened—I do not need to tell you. They killed my father before my eyes. Then the commandant offered my mother to one of the Kash Guard, but she snatched his bayonet from his belt and ran it through her heart before they could prevent her. I tried to follow her example, but they seized me.

"I was carried to my own bedroom on the second floor of my father's house and locked there. The commandant said that he would come and see me in the evening and that everything would be all right with me. I knew what he meant and I made up my mind that he would find me dead.

"My heart was breaking for the loss of my father and mother, and yet the desire to live was strong within me. I did not want to die—something urged me to live, and in addition there was the teaching of my father and mother. They were both from Quaker stock and very religious. They educated me to fear God and to do no wrong by thought or violence to another, and yet I had seen my father attempt to kill a man, and I had seen my mother slay herself. My world was all upset. I was almost crazed by grief and fear and uncertainty as to what was right for me to do.

"And then darkness came and I heard someone ascending the stairway. The windows of the second story are too far from the ground for one to risk a leap; but the ivy is old and strong. The commandant was not sufficiently familiar with the place to have taken the ivy into consideration and before the footsteps reached my door I had swung out of the window and, clinging to the ivy, made my way to the ground down the rough and strong old stem.

"That was three days ago. I hid and wandered—I did not know in what direction I went. Once an old woman took me in overnight and fed me and gave me food to carry for the next day. I think that I must have been almost mad, for mostly the happenings of the past three days are only indistinct and jumbled fragments of memory in my mind. And then the hellhounds! Oh, how frightened I was! And then—you!"

I don't know what there was about the way she said it; but it seemed to me as though it meant a great deal more than she knew herself. Almost like a prayer of thanksgiving, it was, that she had at last found a safe haven of refuge—safe and permanent. Anyway, I liked the idea.

And then Mollie came in, and as I was leaving she asked me if I would come that evening, and Juana cried: "Oh, yes, do!" and I said that I would.

When I had finished delivering the goats' milk I started for home, and on the way I met old Moses Samuels, the Jew. He made his living, and a scant one it was, by tanning hides. He was a most excellent tanner, but as nearly every one else knew how to tan there was not many customers; but some of the Kalkars used to bring him hides to tan. They knew nothing of how to do any useful thing, for they were descended from a long line of the most ignorant and illiterate people in the moon and the moment they obtained a little power they would not even work at what small trades their fathers once had learned, so that after a generation or two they were able to live only off the labor of others. They created nothing, they produced nothing, they became the most burdensome class of parasites the world ever has endured.

The rich nonproducers of olden times were a blessing to the world by comparison with these, for the former at least had intelligence and imagination—they could direct others and they could transmit to their offspring the qualities of mind that are essential to any culture, progress or happiness that the world ever may hope to attain.

So the Kalkars patronized Samuels for their tanned hides, and if they had paid him for them the old Jew would have waxed rich; but they either did not pay him at all or else mostly in paper money. That did not even burn well, as Samuels used to say.