an ebook published by Project Gutenberg Australia

Title: The Escapades of Ann

Author: Edward Dyson

eBook No.: 2300191h.html

Language: English

Date first posted: 2023

Most recent update: 2023

This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore

Chapter 1. - The Righted Wrong

Chapter 2. - The Unbidden Guest

Chapter 3. - Some Adventures with a Flapper

Chapter 4. - A Suitor of Ann’s

Chapter 5. - Miss Gaby, Washerlady

Chapter 6. - The Widow’s Jewels

Chapter 7. - The Sobering of the Prodigal

Chapter 8. - Ann as the Blessed Peacemaker

Chapter 9. - The Losing of Jane Gateway

Chapter 10. - Haunted

Chapter 11. - That Bad Mr. Bighill

Chapter 12. - Aiding and Abetting

Chapter 13. - Those Goo-Goo Eyes

Chapter 14. - A Righteous Deception

Chapter 15. - Playing with Fire

Chapter 16. - Amorous Ling Suey

Chapter 17. - A Morning Walk

Chapter 18. - The Marrying of Arty

Ann Quigley, handsome Ann, with golden brown hair and golden brown eyes, and even a hint of gold in her excellent, healthy, “natural born” complexion. Ann was twenty-five, and still much of a tomboy.

But that’s nothing, Ann would be something of a tomboy at fifty-two. If Ann passed on at ninety and entered into her reward, she would be something of a tomboy in Elysium.

Temperaments like Ann’s are irrepressible and unchangeable, but it must not be assumed Ann had no graver moods; she had all moods at her command, and there were people who knew Miss Quigley for many years, and knew her only as a young gentlewoman of sedate bearing and irreproachable manners. These were unfortunate people, the unhappy ones who are cut off from vivifying fun by some perverse order of Fate.

Ann was spending a week with the Cringles, at “The Whim,” the hill-top bungalow that embodied one of Peter Cringle’s whims. Cringle was an artist who took unbounded joy in the vagaries of Ann.

“When my Art enters into her reward.” he told his wife, “and I have eighty thousand a year, I’ll give Ann half of it to employ herself for the entertainment of me and my friends. Meantime, in God’s name let’s have as much of Ann as we can. Smuggle her in. Life is short, but dull hours are interminable, and there are no dull hours within ten miles of fat Ann.”

Really Ann was not fat, she was “comfortable covered,” as Mrs. Cringle put it, but Cringle was irreverent even in the face of high heaven, and Ann expected no better of a mere artist.

“An artist,” said Ann, “is a barbarian entirely surrounded by paint.”

Ann was resident at “The Whim,” Mount Mistake, temporarily, scampering about the bush, wading the waters, swarming the hills, exuberant, inexhaustible, versatile as usual, when she fell in with Miss Honor Steeple.

But I must side-step here to correct the erroneous impression you have, formed. You are utterly mistaken in imagining that because Ann Quigley swarmed, and waded, and scamp’ered, she presented the appearance of the ordinary mad-cap of literary commerce. Miss Quigley had the amazing knack of doing all these things without getting hot and ruffled or looking conspicuously different from any ordinary, handsome young lady, parading her sartorial, millinery, and tonsorial perfections on the Block.

So when Miss Ann Quigley met Miss Honor Steeple, weeping desolately, sitting behind a tall rock in the fragrant bush, the former was a composed and decorously arranged young lady, not an eyelash out of order.

But Miss Steeple—I hate to say it of a pretty girl with those dense, dark Italian blue eyes, peculiar only to the Irish—was distinctly sloppy. It’s a nasty word, “sloppy,” but if a sweet girl of nineteen will weep copiously all over herself for a space of half-an-hour, what can she expect?

“Why, my dear child, whatever is the matter?” said Ann.

Miss Steeple stopped weeping for one moment, looked up with a startled jerk, discovered a handsome, apparently harmless, young woman looking down at her, gulped, and returned to her fluid state.

“Such a place to cry in,” said Ann, “here in the bush at least a mile and a half from anyone. No pretty girl should bother to cry excepting when some one who might be impressed by it, is looking. Come, my dear, tell me what the trouble is.”

The girl gave an impatient movement. “Won’t!” she said.

“Why not? Perhaps I can help you. I’m a demon helper. I’ve never been able to do much for myself, but I succeed amazingly in other people’s affairs.”

“Go ’way!” sobbed the girl.

“That advice about sticking your nose in other people’s business is simply wasted on me. I’m a hopeless sticky-nose. If I didn’t interfere with those things that don’t concern me, my best talents would be wasted.”

“Go ’way!” repeated the girl, petulantly.

“Come, come, dear. If you go on crying like this I shall have to get you a mackintosh.”

Ann noticed the butt of a cigarette on the flat stone beside the weeping girl, she saw the fragments of torn letters on the grass, she observed a man’s tie on a bramble, and recollected stepping behind a tree to screen herself from Dan Burke as he came striding down the track half-a-mile away—and Ann read Honor like a book—the Book of Revelations, for instance.

So this was pretty little Miss Steeple whom Dan Burke had been courting three months or more. Mrs. Cringle had told her of the pair.

“Don’t let the scamp hang so much about your heels, my darling girl,” said the hostess of “The Whim.” “He’s already got Honor Steeple, the prettiest girleen in the district in love with him, a nice, little, affectionate, sentimental, simple girl, just the sort to break her heart over one of these man things. Now he’s hot-foot to tumble in love with you. Ward him off, dodge him, block him, freeze him—anything to send the creature back yelping to his true mate. He’s half a Yahoo, and you know in your heart you’ve no use for him, you she blackguard.”

And here was little Honor crying her eyes out in the lone bush, and below them was Dan Burke, son and heir of Black Down, blundering towards Cringle’s in the hope of wasting a day with Miss Ann Quigley; and here, too, was Miss Quigley herself, sitting by the afflicted lass, the poor, bruised reed, and trying to soothe her sorrows and put some stiffening into her limp bones.

There had been a wild quarrel, Dan had torn her tender letters, and dramatically scattered their fragments at Honor’s little feet; he had pulled from his collar the tie she gave him, and had returned it with appropriate oaths, and they had parted “for ever,” and possibly she, harmless, well-intentioned, motherly, all-embracing Ann Quigley was responsible for the tragedy.

She sat on the flat stone, took Honor’s reluctant, damp hand, and patted it between her own.

“There, there, there, little girl,” she said, “don’t you cry please. I don’t know you, and you don’t know me, but let us like each other. I am sure I can make you happier. Tell me all about it.”

Honor allowed one eye to escape from her waterlogged handkerchief, and she stopped sobbing while that eye investigated the stranger again. Then the eye was withdrawn, and the sobbing was resumed, but Honor allowed herself to lean towards the nice young woman with the dimpled mouth and the kind, golden eyes.

“Come,” said Ann, “I’m sure it will be all right. Let me see.” She opened the little palm in hers, and laid the hand on her knee, tracing the lines with a finger. “I read fortunes in the hands. I am a palmist and devilish clever. I’ll read your fortune.”

The sobbing was suspended again, and again the tear-dimmed left eye escaped from the handkerchief.

“Why, bless my soul!” cried Ann, “a girl with a palm like this should never cry—she shouldn’t shed one tear, she should smile, dance, laugh. Little girl, little girl, you have the luckiest hand in the world.”

“Have I?” gasped Honor.

“My sweet, your hand is full of good things. It overflows with fortune, and you sitting here crying like a fountain. Here’s the line of long life. Look where it runs. Child, are you ever going to die? See the deep color of it. That means happiness, great, glowing happiness. These little lines are lovely babies. That twisting network means riches. You will never want. There’s a dark man loves you.”

“Oh, does he?” said Honor eagerly, “does he really, really love me?”

“Why, of course he does. There may be tiffs and nonsense of that sort, but see, he comes back. He always comes back. He is dark, and medium tall, French perhaps, or, no, Irish.”

“Yes, yes, Irish!”

“Bless us, you’re smiling. Where are all those tears? The sun has dried them. All’s well with the world.” Ann laughed, and kissed the simpleton on a blushing cheek.

“I like you,” said Honor.

“Of course you do,” said Ann. “It wouldn’t be fair if you didn’t. I like you.”

When Ann Quigley returned to Cringle’s that evening, she found Dan Burke awaiting her. For over two hours he had been endeavoring to maintain an exaggerated interest in art, while Peter Cringle lolled behind a huge pipe, and occasionally swiped a canvas with a paint knife, putting slabs of Goat Hill into a landscape, and amusing himself in a lazy way pulling the leg of the distraught native.

“Burke’s become a patron of Australian art, Ann,” said Cringle, as she entered. “He’s going to encourage the poor painter. He’s bought my ‘Old Barn.’ He says he likes the perspective. He thinks he never saw a better perspective, especially the blue part. What do you think?”

“I’m glad Mr. Burke is buying pictures,” Ann replied gravely. “ ‘The Old Barn’ is a charming thing, and he’s right, the perspective is all that could be desired.”

“There,” said Burke, joyously. “I’m right, yeh see. ’Tis ez fine a bit iv perspictiff ez iver was painted, so ’tis, ’n’ I’ll be makin’ a present iv it to Miss Quigley.”

But Ann refused. She could not dream of it, she said. Mr. Burke must keep his presents for those who had greater claims upon him.

Had Honor, seen Ann Quigley with her Dan for the rest of that evening, she would have imagined the good Samaritan of the woods to be a traitress and a base deceiver. Ann was coquetting with Dan openly, audaciously.

“She devil,” said Mrs. Cringle pulling Ann into a bedroom after dinner. “What are you doing with that raw product?”

“I’m entertaining your guest to the best of my ability, Mrs. Cringle,” Ann replied sweetly.

“Entertaining him! Engrossing him, entangling him. And you know what I told you about his ‘ain true love’ the sweet Honor of the hills. Wretch, you are trifling with two lives.”

“Oh, Mrs. Cringle, how cruel you are. Are the natural cravings of woman’s true heart to be trampled out for the sake of this bush hoyden of yours.”

“Natural cravings of pickled pigs’ feet! This Dan Burke is a well enough lad on agricultural and pastoral lines. He suits Honor, and Honor suits him if you are not a meddlesome hussy. He’s a great simple jackanapes born here, but more Irish than the primitives of old Sligo. Why, his brogue’s as thick as his father’s, and he’s as superstitious as his ancient grandmother who once boarded the pigs, and who now nods in the chimney corner over a black pipe, and mumbles of the banshees of her native hills, and is said to be one hundred and two. The fellow’s preparing to make an egregious ass of himself over you, and you’re accelerating the process, you—you, Circe, you!”

“Circe changed them to pigs, I fancy.”

“The modern Circe makes asses of them. But I won’t have it in this case. I’ll bundle you off home first.”

“You’ll bundle me off?” Ann danced away, laughing. “You’ll bundle me off? I’d like to see you do it, Mother Cringle. Who’s boss of the master of this house, you or I?”

Mrs. Cringle threw a pillow at her. “Infamous wretch!” she said, “if I knew where I could get another like you I’d banish you on the spot.”

Ann danced back and kissed her. “Trust in the notorious fat, soft heart and the justly celebrated high principles of Mistress Ann Quigley,” she said.

But Ann’s attentions to Dan were even more marked in the two hours after dinner. Then she said an abrupt good-night, and towed Mrs. Cringle into her room.

“Keep him for another ten minutes,” she said. “For the love you bear me, hold the catiff knave yet awhile.”

Tom Burke said “good-night” to Mrs. and Mr. Cringle at the door, he passed down the garden path and stopped a moment to look back at the house, and sigh deeply. “Sure, was their iver a divil iv a gir-rl a shweeter tormint than that wan!” said he.

He went through the gate, and out on to the bush track, and passed on with his back to the big moon. Suddenly, from behind a patch of sappling scrub, a woman arose and confronted him.

Dan Burke jumped back. “Saints presarve us, all, ’n’ ivery wan,” said he.

“There’s nothin’ in an old woman ye nade be fearin’ at all, Dan Burke,” said the stranger.

“Ye are knowin’ me good name then!” Burke peered at her, keeping his distance. He saw a bent old woman, with disordered hair and large glasses. Her feet and her head were bare. She looked more like a wrinkled Jewess than an Irishwoman, but her brogue was unmistakable and her ugliness hurt him. “Sure, I don’t know ye’, do I this night? ’n’ me knowin’ ivry dacent soul in the disthrict, man, ’n’ woman.”

“Ye know me not, Dan Burke, nor any wan else ayther. I’m Winoora the gypsy iv wild Nephin Beg, ’n’ all the long way I’ve come to tell yer fortchin has blisthered me poor feet ’n’ put the mortal pains in me ould bones. So set out yer hand, Dan Burke, ’n’ I’ll be readin’ the tale iv yer bad life.”

“I will not the like.” Dan put his hands behind him. “I’m not wishful to hear the devil’s folly ’n’ wickedness yid be talkin’, ’n’ you an ould, ould woman should know better.”

“Lave out yer hand, Dan Burke.” Her voice was so awful, she advanced upon him so threateningly, that he threw out his hand and stood trembling as she read.

“Ah, ah. ’tis well I’ve kim this far way,” said the gypsy of wild Nephin Beg, “well for you, Dan Burke. The danger is wid you, great sore thrial will come to you, me man, ’n’ long sorrer ’n’ sore nights ’n’ sufferin’ days do ye not heed me. ’Tis one woman that loves yeh I see here, a wee, shmall gir-rl wid the thrue dark eyes if the good folk iv Clare. She would make happiness ’n’ riches in plenty for yeh t’ the ind of yer days; but another there is will desthroy yeh do yeh yield to the ar-rts ’n’ wiles iv her—a base Sassinach she is wid the bad hear-rt and the fair shkin iv her thribe ’n’ wid fair goold to her hair, too. She’s kim frim far t’ be the roon iv yeh, ’n’ t’ dissipate the land yer good father would lave you, ’n’ t’ waste the flocks ye have ’n’ spend the money all frim yeh, ’n’ lave yeh dislate in yer age, creepin’ be the hollow places iv the hill t’ shleep in. Go, man, go ’n’ lave the wicked tempthress wherever she is?”

“Would she be the gir-rl beyant?” said the horrified Dan throwing his right thumb towards Cringle’s. “A shmart, plump fair wan from the city? Would it be Ann Quigley, yeh thinkin’ of would bring the dire misforchunes iv the divil down on a man?” Dan was quaking with apprehension.

“ ’Tis most like,” said the gyspy. “Yill know her well. Get from her ’n’ hade her no more, fool that ye are.”

Dan fled up the track. The gypsy watched him over the hill, then hobbled to Cringle’s door and knocked. Mrs. Cringle opened to her, and she hobbled into the lighted room unasked, a weird old figure.

“I’ll rade yer fortchin’, kind sir,” she said. “Lave me rade yer fortchin, shwate lady, fer the bit iv bread, ’n’ the Lord love yeh ’n’ reward yeh.”

“Read my fortune,” yelled Cringle. “No, not on your life, but by the living jingo I’ll give five pounds to be permitted to paint you.”

“Done!” said a youthful voice, a shawl was thrown aside, a wisp of hair and a pair of spectacles cast off, and Ann Quigley stood revealed.

Cringle collapsed into a chair. “Merciful heaven!” he cried, “you’ve spoilt the best study of a d——d old witch that was ever conceived. Is there anything you can’t do with that amazing prehensile chiv of yours?”

“I can do it all again,” said Ann, “and you shall paint it. I want the picture for a wedding present for a friend of mine.

When, two months later, Honor Steeple was married to Dan Burke, Ann Quigley sent the bride a fine study in oils of the head of a witch, called the Gypsy of Nephin Beg.

“Did yeh see her, too?” said Dan to Cringle one day, pointing to this picture.

“I did,” the artist replied, “she came to me one night, and insisted on being painted. ‘ ’Twill be a war-rnin’ to Dan Burke all his life,’ she said. Now, what the deuce did she mean?”

“I dunno; I dunno!” said Dan hastily. “How the divil should I? Fer the love iv heaven, man, don’t let me little wife be hearin’ such wild talk.”

Ann Quigley, being a happy woman, her escapades have a way of ending happily.

Ann realised she had kissed a strange man, and a strange man in bed! It was a gritty kiss, a wholly unfamiliar kiss, suggestive of a chaste salute on a superannuated hair-brush.

Realise the situation. Here is an extremely nice-looking, plump, comfortable spinster of twenty-four, of exemplary conduct, standing over the couch of an imperfect stranger after having deposited an affectionate oscillatory caress on his right cheek.

Evidently the imperfect stranger had pondered his scriptures well. “If thine enemy smite thee on the right cheek, turn thou the left.” He made mumbling noises, and turned on his pillow. The left cheek was now available, but Miss Ann Quigley had done all the smiting she cared for, pending inquiry.

The shock of that gritty contact left her much perturbed and dubious. She stood for a moment irresolute, wondering. The next impulse was to run, but Ann Quigley was no ordinary girl; she had a pronounced drift to adventure. Her disposition prompted her to see things through.

This is how. Miss Quigley had just returned from a night at the theatre, and a somewhat belated supper. She had parted with the party at the gate, and tripped across the front of the house towards her side entrance. Here at the south-east corner of “Wattleholm” was an unsuspected little brick adjunct, half-sleeping apartment, half-verandah, open to the seven-and-twenty winds of heaven and the concomitant dust, not to mention mosquitoes, or even larger game—say, a casual intrusive cow.

This was Billy Quigley’s sleeping place when Billy was at home; but Billy was a nomad, with a glib manner and fourteen bags of samples, and his duties led him many ways, and his homecomings were infrequent, and his stays not protracted. At the present minute Billy Quigley should have been in the Albury vicinity with the object of selling profuse softgoods adapted to the requirements of an agricultural population.

Ann had not expected Billy home for a week, but, noticing his bed bulging (Billy had the open-air habit), she rashly assumed that he had returned unexpectedly, and she slipped in to give him a sisterly kiss.

Having deposited the kiss, “My goodness!” said Ann.

It was as if you had arisen at night to take a cooling drink, and had connected with the bottle of methylated spirits by mistake. Billy Quigley’s cheek was notoriously smooth (it had even been called brassy). This one was decidedly stubbly.

Ann started back; Ann pondered perplexedly for a moment. Ann repressed a tendency to squeal. Ann overcame a disposition to run.

“I’ll see who it is if I die for it,” said Ann. Her hand went up to the electric switch, she touched the light on. She touched it off again.

One glance had been enough for Ann. The face on the pillow was that of a sleeping man. Ann had proof of the soundness of his slumbers as she fled tip-toe for the side door. A purling snore followed her.

Miss Quigley arrived in her room greatly perturbed. She dashed for the water jug, and, displaying some temper, washed her lips. She snatched the toothbrush, and, with actual ferocity, cleaned her-teeth. Then, feeling in some measure sanitary again, she stood up and thought.

The man on the open-air bed, of whom she had caught a glimpse in the flash of the electric light, was not her brother Billy; he had not the remotest resemblance to her brother Billy. He was a red-faced man, a little bloated, with thin, tousled hair that looked like a limited quantity of old combings in a dustbin. On his jaws was a thick, dark, stubble of at least a week’s duration, and he had a large, sordid nose, that lay against the white pillow like a mottled toad. Scattered on the cement floor was a litter of garments, not the trim habiliments of a popular and attractive young salesman, but the loose, desultory fragments of a tramp. Ann had not missed even the boots. They looked like two outworn and distorted Gladstone bags.

The solution was plain to Ann. This villainous, unkempt, unlaundried dead-beat had crept into the verandah and taken possession of Billy’s bed. Probably he had often done so before. The verandah was fairly cut off from casual observation from the parts of the house occupied by the family, and any homeless tramp might have used the downy couch regularly by showing circumspection, retiring late and rising early.

And she had kissed him! She had actually kissed the brute—“Cuh-h-h!” Ann Quigley spat, and made loathy grimaces at herself in the glass. “Kissed him? I kissed him! Suppose I catch something. Oh, the beast!”

Another girl would have screamed in the first place. Another girl would have rushed to the family for succour. Ann had small faith in the family methods. Her own schemes usually provided more amusement, and were always more effective.

Ann sat down and thought. After brief thinking Ann arose, and stole out into the garden again. She found the long-handled rake, and, creeping to the door end of the verandah, she, guided by a fitful moon ray, reached in, and raked out the sleeper’s garments, boots and all.

Carrying the objects on the rake, Ann deposited them under some straw in an outhouse. Then Miss Quigley, with no compunction, and not a figment of apprehension, went quietly back to her room, undraped, said her simple prayers, and retired for the night.

Miss Ann Quigley was up very early next day. In fact, it was not yet quite daylight when she stole to Billy’s room, and peeped out from the blind covering the half-glass door. Weary Willie was still abed, sleeping sweetly (at least, quite as sweetly as such an insanitary pagan could sleep), and purring like a sawmill.

Lightly and gaily Ann dressed herself for the day. Ann had a plump girl’s affection for bed, but there are occasions when our softest and dearest desires must be sacrificed to duty. Miss Quigley had a keen sense of duty.

Dressed, Ann went into the yard, and loosed Canute, Canute the Nut, bandy as a barrel, and with a face like the composite picture of seven murderers and the thirteen deadly sins. Canute was a fawn bulldog with pale gold patches, and as amiable a creature as ever bit the leg of a butcher’s assistant, or gathered samples of the pants of hapless postmen.

Ann put one of Weary Willie’s boots in the capacious and capable mouth of Canute the Nut, and went softly round the house under the mulberry trees. There she knelt on the grass, and, drawing the bulldog to her, gave him confidential instructions.

“Sool him!” she said. “Watchim, Canute!” she said. “Watchim, boy!” She spoke in whispers.

The dog seemed undecided for a moment, and capered in a cumbersome, lubberly way. He thought it was a game.

“Watchim, boy!” whispered Ann, and the Nut went forward to inquire further. At the verandah entrance he struck a strange line in scents; his unkindly eye fell on Willie. He stood with the boot in his mouth, and growled. He growled again, keying to a higher note, and throwing in a little more feeling.

Ann heard movements in Billy’s bed round the corner. She crept nearer and listened. A soft, ingratiating voice was saying:

“Good boy! Good boy!” Then the voice lost kindness. “Lie down, yeh bleedin’ swine!” it said.

Miss Quigley hugged herself, and giggled inwardly. “Watchim, Canute!” she whispered.

“Staggerin’ Bob!” came the anguished voice of the unbidden guest, “he’s got me clo’s—he’s pinched me clobber! Here, boy! Here, boy! Good dog!”

Canute’s back hair stiffened like the quills of the fretful porcupine; his growl was deeper, it breathed threats of sudden death. There was a plunge in the bed again. Weary Willie had decided that it would be inadvisable to make further advances at the present moment.

“Watchim, boy—watchim!” whispered Ann.

Canute settled down on his stomach, and levelled his eyes at the stranger in the bed. He was prepared for a long day.

Ann went in and had two hours’ sleep. When she looked from her window at half-past seven Canute was still holding the intruder with his eye. She stole to the glass door and peeped out. Weary William was abed; his eye, full of apprehension, was fixed on Canute; his face had lost much of its ruddy color; even his nose was grey with anxiety.

Ann Quigley had breakfast. She said nothing to her mother. She did not mention matters of any particular interest to her little sister, Violet. She even allowed her father to depart to the duties of the day without enlightenment. John Quigley was a short, round, petulant man, with small sense of humor, and an inveterate habit of spoiling the picture.

“He would just storm in in a condition of outraged respectability, and kick my poor tramp into the road,” mused the dutiful daughter. “I won’t have it. He’s my tramp, I saw him first, and I’m sure I can make him interesting, and give him a good day.”

Ann giggled over her egg, and hugged herself.

“Ann,” said her mother, in admonitory tones, “whatever ails you?”

“Nothing at all, mother. What should ail me? I was thinking of a dream I had last night.”

Half-an-hour later Ann was out in front, watering the lawn. She had never been so determined to water the lawn. While she hosed the grass, she held quite an animated conversation with her sister. Behind the barrier of the verandah front, just high enough to hide the bed, the intruding tramp huddled in the blankets and quaked; round the south-east corner, hidden from the lawn, Canute the Nut lay extended, his gaze fixed upon the bed, every exaggerated tremor of which drew from him an ominous growl.

“You should be ashamed of the way you’ve neglected this lawn, Vi,” said Ann. “It’s not been watered for a week. I’ll set the spray, and leave it for an hour or so.”

She set the spray, and then, flying at Violet, dragged the bewildered girl away, with a palm tight across her lips.

“Do shut up, you silly ass!” hissed Ann, when they were safe out of range.

“But it’s all going into the verandah.”

“I know it is.”

“It’ll wet Billy’s bed through and through.”

“I know it will. Now, don’t you yell, or I’ll pinch your ear clean through. I’ve got a man there.”

“A man!”

“Yes, one male adult. Don’t you fret, the water will do him no harm. He’s sneaked in to sleep in Billy’s bed. I’ve got him fixed. I’m going to make a day of it. Come and see. But not a word to mother. She’d want to give him his breakfast and her blessing, an old suit of clothes, a cure for rheumatism, and pack him off to lead the better life. And it ain’t fair. He’s mine. I’ve got nothing to do to-day, and I want to give Willie an eventful time in case he should want to come back to that bed again.”

The girls stole to the glass door. Each took a corner. Weary Willie, sodden beyond recognition, had got out and got under. Wrapped in a dripping rug he was beneath the couch. The hose was throwing a heavy shower on to the bed. A stream was running under Willie on the cement floor, and Willie lay, drenched, with an apprehensive eye upon Canute, who watched proceedings in a wholly dispassionate way, only growling when Willie’s movements hinted at an advance or a retreat.

Ann dragged Vi into her bedroom, and then she curled herself up into a sort of convulsive knot on the bed, and kicked and gasped.

“It’s lovely! It’s lovely!” she chortled. “I’ll keep him a week. He’s mine, and I’ll keep him a week.”

“The poor wretch will catch his death of cold,” said Violet.

“Not he, and he’ll be a nice, clean boy. The police won’t know him. He ought to be grateful for that. A bed and a bath for nothing! Keep mother away. For the love of goodness, don’t let her spoil this on me! Darling, what a playful sister you’ve got!”

Ann did not keep Weary Willie in his flooded bed a week, but she retained him all morning while she busied herself weeding the front garden. Willie had got back into the bed. It offered the only cover available for him, wet as it was, and he hadn’t a stitch to escape in, even if the detested female singing gentle ditties over the weeds would go, or the loathly bulldog would avert its cold gaze for a moment.

It was just before lunch that an idea for a suitable climax struck Ann, and she had curious convulsive movements on the lawn in inward appreciation of the primitive humor of it.

“I wish you would bring me mother’s old sun-bonnet and that butcher’s blue skirt of mine, Vi,” she called. “I’m getting woefully sunburned, and just spoiling this dress.”

Vi brought the articles, and Ann let them lie on the lawn for awhile, then threw them carelessly into the verandah. “After all, it’s lunch time,” she said.

She led her sister away, and, skipping hastily round the house, called Canute off. The dog responded, and Ann held him under cover of the mulberry trees. “Now, watch,” she whispered ecstatically.

They had hardly two minutes to wait before a quaintly garbed figure in a tattered shirt, and old skirt of butcher’s blue, and a large poke bonnet sprang from the verandah, fled across the lawn, darted through the front gate, and scampered down the sunlit street. Then Miss Ann Quigley sat down on the grass, a raffish object, with tumbled hair, and laughed until her mother came forth in a state of terror, and threatened to apply the rules for the resuscitation of the hysterical.

But Ann’s escapade with the dead-beat did not end there. At about four in the afternoon she heard a clatter in the front street. A large policeman was passing. Behind the policeman followed a long, curious mixed crowd of interested and derisive spectators. The policeman’s grip was on a red-faced object with a profuse dark stubble and a booser’s despicable nose. The object was clad in an ancient poke bonnet of huge dimensions, and a woman’s blue skirt.

It was Ann’s dead-beat under arrest, as she imagined, for impersonation, and being illegally at large in clothes unbecoming to his sex and station.

Miss Quigley headed off the procession. “What has the poor lady been doing!” she asked demurely.

“I dunno yet, Miss,” said the officer, “but she answers to the description iv a dame missin’ from Yarra Bend Asylum. If she’s not that one, I’ll lag her on the vag.”

“Whiskers are no protection to a man nowadays,” was Ann’s unspoken comment.

“Goodness preserve me from the flapper!” said Ann, talking for the edification of a select winter evening gathering. “More especially the Australian flapper—the least tameable and most virulent of the species.”

“Have you noticed how the indigenous flapper falls in love? You haven’t! There’s a conspiracy of silence on this point, otherwise miles of treatises would have to be written on the subject, with a view to enlisting the services of science to modify the symptoms.

“The favorite assumption is that the Australian damsel of fifteen, sixteen or seventeen—they even sprout at fourteen—is a simple, girlish thing, with a penchant for skipping, and a taste for bread-and-butter sandwiches sprinkled with ‘hundreds-and-thousands,’ and whose highest idea of dissipation is the dancing mistress’s semi-annual hop, where she dances with George, aged twelve, a smudgy lout with an impediment in his feet (whose whole intellectual impetus is absorbed in the ravenous consumption of buns).

“How different are the facts! In very truth, the flapper who is a local product (the imported item is tamer, I admit) is an impetuous and irresponsible young thing, with no particular respect for any living being or known law. She thinks her parents archaic, and regards their mild rules for her better government as relics of the Inquisition. She is that hot-headed, she boils the cherries in her hat, and her specialty is falling in love.

“Don’t wag your wise heads, and ‘No, no, no!’ at me—I say, yes. In nine cases out of ten the darling little Lucy whom mamma regards as so fresh, you know—an unspotted flower culled from nature’s garden, and who is to be kept from all knowledge of the world and its ways—is cherishing a secret passion for Binks, her father’s best friend, an unconscious bachelor with soulful eyes and picturesque patches of grey in his abounding hair.

“I have enjoyed the confidence of the flapper for ages. Something in me invites the trust of the adolescent anarchist of fifteen. I don’t respect that trust; but I get it, and I tell you the flapper can fall in love with a readiness that would throw her unsuspecting mamma into a fit, and give her sage papa, if he only knew, moral jim-jams.

“And how the little lass does love, and how she does hate the other creature that absorbs some of the attention of the beloved! Believe me, gentle Annie makes no bones about it when she bestows her virginal affections on a male object. The recipient of her favor becomes a young god; there is no word in the language too good for him, although to the cold, critical eye of the uninspired, he may be a rather commonplace lad, with more than a human allowance of hands and a capacity for being infatuated with nothing of greater spiritual significance than cheap cigarettes.

“Take Betty Parsons, for instance. Betty was not sixteen at the time, when she confessed to me her wonderful love for Harold.

“You don’t know Harold Carr. He was a plump boy about twenty, with a musical soul, and hair enough for the conductor of a Wagnerian orchestra.

“Harold played the fiddle somewhat, and was a nice lad, although he did suffer in one’s elderly estimation from the fact that his parents had done their best to make a wholly unsatisfactory kind of girl of him.

“ ‘Oh, isn’t he a love?’ said breathless Betty. ‘Isn’t he a darling, darling dear?’

“This confidence exuded when a pack of us, loaded in a van, were going for a river side picnic. Harold was at the other end of the conveyance, nursing his fiddle case (he was scarcely permitted to venture abroad without it), and discussing the arts with Jess Mason, then a slip of fifteen.

“ ‘I think he’s just beautiful!’ sighed Betty. ‘Don’t you?’ Such wonderful eyes. And his hair— oh! isn’t it lovely? I think he has such clever hair. Don’t you? Don’t you think his hair’s clever?’ Betty sighed again, and relapsed into half-a-minute’s silence, gazing at the plump Adonis, with soft, sad, soggy, devotional eyes. ‘Isn’t his mouth sweet?’ she said. ‘Just like Cupid’s bow. Wouldn’t you like to kiss him? I’d just love to.’

“Another burst of devotional silence, punctuated with sighs, and then: ‘I’ve been in love with him such a long time—years and years. We met first at a picture show a month ago. We were made for each other. Don’t you think so? I do think he has clever hair. Such an adorable wave in it! He doesn’t care a button for Jess. You don’t think he does, do you?’

“More silence and more sighs, and then: ‘Don’t you think that mole on Jess’s chin looks beastly? She’s nothing, is she? Commonplace. And her eyes! Green they are, and too close together. I’m sure he must see they’re too close together.’

“Silence and sighs, ending with a reflective: ‘Yes, she’s a little beast! No fellow with taste could really love her. Do you think he could? Really, now, do you think he could? Really, really, positively?’

“I said I didn’t think a young man with clever hair could be taken in by Jess’s specious attractions. ‘Not if his hair is really clever,’ I added.

“Betty seemed relieved. ‘Oh, I’m so glad you think so,’ she said. ‘Not that I’m afraid of her. She’s a cat! But men are so easily deceived in girls. You’ll manage to let me have a talk with him at the picnic, won’t you? Keep her away, there’s an old dear. And if you could arrange to have him sit next me riding home, I’ll never, never forget you— never, never ’slong as I live.’

“I promised to do my utmost; but Miss Jess Mason was a cute lass, too. She had her own idea of what should happen, and had all a flapper’s charming disregard for any arrangements that might conflict with her own, coupled with a flapper’s line contempt for general opinion and the censure of her elders.

“Jess practically monopolised the adorable Harold throughout the morning. While she lay in a bed of bush hyacinths, Harold leaned against a tree, and scraped sentimental melody out of his fiddle. Poor Betty was conspicuously miserable when she was not absolutely virulent.

“Once she came to me, concealing something under her skirt. ‘Look,’ she said, revealing the prize. ‘It’s her hat. I sneaked it from among the rest. I hate her. Huh, the wretch!’ She tore out a feather. ‘The beast!’ She tore out another feather. ‘The ugly little minx!’ She tore the rim.

“I rescued the hat before it was wholly demolished, and the ruin was smuggled back; but Betty was a small tempest of wrath.

“ ‘Look at her!’ she cried. ‘Look at her gazing at him with her silly green eyes—and he hates her. I know he hates her. He must. If I had some poison I’d put it in her tea. I would!’

“It was at about half-past four when the catastrophe happened. There arose a great hubbub, and I joined the rush to the river bank. Someone had fallen in, of course.

“Presently a bunch of dark hair came to the surface, a gasping white face was revealed, and I recognised Miss Betty Parsons. Brown, the van man, went in and brought her out. You have read much of the touching gratitude young ladies display towards their saviours in such circumstances. Forget it, and hear.

“Poor Brown was bearing Bet up the bank, when she opened her eyes. The homely face of the man Brown upset her. She grabbed his hair and tore it.

“ ‘You let me go!’ she gasped. She pounded his nose with her two hands. ‘How dare you save me!’ she said. ‘How dare you, you nasty man? I won’t be saved by you. I won’t, I won’t!’

“Poor Bet made home in a composite costume. We all contributed a little to her make-up. She was utterly wretched. The ravishing Harold was at the other end of the van with Miss Mason. He graciously permitted Jess to nurse his head.

“ ‘I don’t care! I’ll kill myself, or something!’ whispered Betty. ‘When I’m dead, he’ll have a broken heart, and serve him right. You said you’d arrange to have him sit next me going home, and you haven’t. I’ll never forgive you.’

“ ‘You should not have fallen in the river, and made yourself unpresentable. You’ve simply got to be stowed away in a corner,’ I explained.

“ ‘Didn’t fall in the river!’ snapped Betty.

“ ‘Oh, didn’t you?’

“ ‘No, I didn’t. I jumped in.’ She commenced to whimper again. ‘I jumped in on purpose. I thought Harold would rush to save me, and that nasty man Brown did it. It’s hateful to be saved by a vulgar, common, working man. I wish I was dead. You don’t think Jess Mason pretty, do you? She isn’t as good-lookiug as I am? You’re sure she hasn’t as nice hair as mine? Are you quite, quite sure and positive? Say you wish you may die if it is.’

“I made an effort to console the little termagant, but was far from successful, and when I left her she was considering rash projects for disposing of her rival, most of them derived from undue familiarity with the plots of melodramatic picture plays.

“But before we parted I made the brat a rash promise. ‘I undertake that Harold will dance with you at least four times at Miss Blue’s fancy dress ball,’ I said, ‘and I promise you on my sacred word of honor Jess Mason won’t be much in your road for that night, at any rate.’

“Betty was enraptured. ‘Oh, will you do that for me—will you, will you?’ she said rapturously. ‘I’ll love you till my dying day if you do.’

“Well, Betty Parsons did get four dances from Harold at the dancing mistress’s, fancy dress ball, and Jess Mason did leave the field free for her with the adolescent fiddler.

“In point of fact I had contrived that Jess should have her whole attention absorbed by a ravishing Romeo, the loveliest Romeo that ever pranced in doublet and hose—a brown-eyed, pink-cheeked, sort of a fellow, with a lily-white hand and billowing curls that were both chestnut and gold, and adorned with the daintiest imaginable little silky black moustache.

“Romeo made a dead set at Jess early in the evening, and in the course of their first dance bore her right off her feet with a battery of such judicious flatteries that from a state of gasping incredulity she rapidly arose into that condition of elation in which a flapper soars when convinced of the reality of her transcendent charms, and she realises that she enjoys the bitter envy of all her friends.

“The porcelain Romeo was a great success with the girls. Even Betty was content to leave her now attentive Harold to step a measure with him; but he was true to Jess Mason, as per arrangement, leaving Betty Parsons in undisturbed possession of Harold Carr, of the clever hair.

“Master Carr, finding himself quite out of it with Miss Mason, who even jilted him of the dances booked to him in order to enjoy them with her Montague, gave Betty all his attention, and Bet should have been happy.

“But, as I say, you never know these flappers. At about a quarter to eleven, when the Shepherdess (Jess) and Romeo Montague, having escaped the vigilant eye of the dancing mistress, were enjoying a tete-a-tete behind a bed of roses, their communings were suddenly confounded by the arrival of a tempestuous Pierette.

“ ‘I hate you, Jess Mason,’ said Pierette without preliminaries. ‘I hate you! I hate you! You’re an ugly little, green-eyed pig, so there!’

“Jess took refuge behind her Romeo. ‘Oh, don’t let her hit me!’ she whimpered.

“But Romeo was not smart enough to ward off the impetuous Pierette, and Betty fastened in Jess’s hair, and did some damage to the coiffure of the Shepherdess, and her Watteau draperies before a separation could be effected.

“The afternoon following the Cinderella, Miss Betty Parsons called to see me. The flapper flapped even more than usual, and her air indicated a settled wretchedness.

“ ‘Well,’ I said, ‘did you enjoy yourself at the ball?’

“ ‘No, I didn’t,’ replied the ingrate angrily. Then she relapsed into tepid sentiment. ‘Oh, I am in love!’ she said. ‘And I want you to help me.’

“ ‘But I did help you,’ I protested. ‘I arranged that you should have Harold pretty well to yourself at the ball. Didn’t my agent keep his promise?’

“ ‘Oh, yes, I suppose he did. I wish you had been there. If you could only have seen him. A darling —a beautiful darling! I love him fit to die!’

“ ‘Meaning Harold?’ I said.

“She was too wrapped up in her devotions to heed me. ‘He’s the loveliest ever, and I want you to help me. If you won’t, I’ll just drown myself, or eat powdered glass, or something, I know I shall. There was never anyone as much in love as I am. I could die of it easy.’

“ ‘Then Harold wasn’t nice to you, after all!’

“ ‘Harold Carr? Pooh, him! Who’d die for him? That podgy fool! I don’t care if I never set eyes on him again, and I’ve told him so. Did you ever see such an idiot with a fiddle? And the way he does his hair—make you sick, wouldn’t it? He’s coarse. I never really cared for him. I didn’t know what love was yesterday.’ She placed her hand on her heart, and sighed deeply, looking far, far away. ‘I wouldn’t have believed a boy could be so beautiful,’ she said. ‘And nobody knows who he is—unless it’s that beast, Jess Mason. You’ll find out for me, won’t you? Get hold of her and pump her. You don’t know how I’ll love you if you do this—and you can, you’re so clever. He had fair hair, and dark-brown eyes, and the nicest mouth ever, and his hands—oh, beautiful! Smaller than yours they were, and whiter.’

“ ‘But who is this paragon?’ I wailed. ‘How am I to ferret him out?’

“ ‘Jess Mason knows. He was a Romeo at the ball.’

“I collapsed. I simply went down on a rug, and laughed till I wept. Here was a pretty ending to my noble plot to give Betty a free field for her adored Harold. She had actually fallen in love with my decoy.

“For fully a month after I continued to have pathetic appeals from Betty concerning the identity of the lost Montague. During the first fortnight I was three times consulted with regard to the most suitable method of ending a love-blighted life.

“But I never unearthed the long-sought Romeo. I couldn’t very well. You see, I was he!”

His name was Springer. He was a quaint little old buck, a study in pink and grey. He had a grey moustache, and grey hair, and his face, shaven miraculously, was the color of the pulp of a ripe water-melon. He dressed rather elaborately in grey, with aggressive white spats.

On a long, thin, black silk ribbon about Henry Springer’s neck, was an eyeglass, with a miraculously thin, golden rim. Henry favored pearl colored gloves of almost impossible newness, and had a penchant for gay little soft felt hats, carefully curled in the rim, artfully tucked in at the crown.

Henry was extremely thin, he had a jerky movement of one leg, which limb was occasionally mutinous, and refused to go the way he wanted it to go. At such moments it seemed to run on the loose, and bend almost any way but the right one. For some time Ann was dubious about that leg, believing it to be a mechanical adjunct built of light woods, and animated by a small electric motor that was disposed to jib.

Later, however, Ann satisfied herself on this point with the aid of a hat pin. The vigor of Henry’s movements and the fervor of his remarks quite satisfied Miss Quigley that she had done the wayward limb an injustice. At any rate it was real.

Mr. Springer may have been seventy. He acted as if under a delusion that he was still thirty-six, and affected a great sprightliness of manner. Ann loved to see him coming down the garden path, hat in hand, well raised above his head, eyeglass home, a bouquet in his other hand, jigging jauntily, and cackling his usual greeting although still thirty yards distant.

“Momin’, mornin’, momin’,—good mornin’, Miss Ann.” Then when he reached her it was: “How, how, how, how, how are you, how are you, how are you?”

This was Henry’s conversational method. It made a little matter go a long way. Ordinary folk make the most of the weather as a theme of discourse, but Henry Springer could get more talk out of a single, simple, astronomical fact than any other person of my acquaintance.

“Fine, fine, fine,” he said, “fine day, Miss Ann, fine day, fine day, fine day. Ah, yes, by jove, fine, fine, fine, fine.”

It is, perhaps, not quite correct to say Ann encouraged Henry as an admirer, but we may as well admit she did nothing in those earlier days of their acquaintance to discourage the old buck.

“I can’t understand you, Ann,” complained her mother fretfully. “Why will you have that silly old man dangling after you?”

“Mother, where’s your worldly wisdom? He’s very rich.”

“Gracious goodness, girl! you don’t mean to marry him?”

“And his motor car is a darling.”

“But—but.”

“And the chauffeur’s nice. I love dark-blue eyes in a brown face.”

“Are you ever serious? Can one ever tell what to make of you?”

“Mother, you can’t appreciate Henry Springer, the real bullfinch. No one, I think, but myself, can derive the perfect, almost heavenly, gratification Henry is qualified to bestow.”

“Ann, you’re mad. That wheezy old man. Why, he creaks!”

“So he does, bless his old bones.”

“And he barks.”

“He does, the darling. That’s why I love him. He’s perfect. He’s delicious. I can just sit for an hour, hugging myself over Henry.

“Think now, if he were on the stage in a comedy, with that eccentric and wilful leg of his, that imperishable, if ancient, vivacity, those clothes, that hat, and that explosive gatling-gun conversational method, how the world would laugh itself ill at him.

“Why should it be necessary to put him on a platform, and soak him in limelight to bring out the perfectly delicious comedy of him? Why cannot people enjoy such a duck to the full, in his natural setting?

“Lord! Lord! what the world loses for the lack of a hound’s nose for the truly grotesque. Part with Henry? Never! He’s the joy of life, the salt of the earth. I can sit down on my little lonesome, and laugh by the hour at mere recollections of Henry. Half-an-hour with Henry in the garden, is better than anything in Falstaff—better than Bernard Shaw’s best.”

Ann more than anyone else I have known, could extract the nutriment of humor from old nuts. She would sit by the hour with creatures others had voted intolerable bores, taking keenest delight in their foibles and follies, stowing up their idioms, their quaintnesses of expression, their tricks of limb, the very essence of their dreariness, for future use. At reproducing all such Ann was an artist. She found food for laughter in the most unpromising material, and it was only when she faithfully re-enacted her characters that others were given to see and feel the delight of them.

Ann Quigley had the happy faculty of inward laughter. Humanity was an inexhaustible spiritual feast for her, and a new character a thing more to be desired than jewels and fine gold.

This appreciation of the rich and rare, made Henry Springer very welcome. He was a mine of fun, and Ann worked the vein for every pennyweight.

Henry had been introduced by a merely casual acquaintance, and had attached himself to bounteous Ann, and he followed up the chance with wonderful assiduity in one so old and so creaking.

“Like you, my girl,” he said. “Like you. Like, like, like, like. Yes, ah fine—fine, fine, fine.”

“You are very gallant,” said Ann, masking the twin mischieviousnesses behind her brown eyes.

He stopped in their walk, he screwed his eyeglass hard home, he looked at her through it. It seemed that he was very much impressed, that some observation of very gravest importance was about to be made, but he only said:

“Gallant, gallant, gallant, gallant. Yes, by Jove, gallant. Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes.”

Then he emitted the queerest cackling sound, such as might be made by shaking a longish thin piece of tin. “Like you,” he said. “Like you, like you.” And he cackled again. “You make me laugh,” he said. “Laugh, laugh, laugh, laugh, laugh.”

That was it, he was laughing! Then there was the leg. Oh, it was a perfectly lovely leg. Henry would be walking along, head up, eyeglass twisted in, gloves dangling, dapper, and smart, making excellent progress, when all of a sudden the wretched left leg would go back on him, pull him up short, and wobble in a most disconcerting way for a second, before resuming ordinary movements.

At such moments Henry displayed exemplary patience; he merely waited for the leg. His air seemed to say: “Don’t let us excite ourselves. On the contrary, let us pretend we do not notice it, and it will be all right.” Then he would emit a “Ah-h-h!” of no particular significance, and resume his march.

Ann Quigley adored that leg. She contrived with long effort to imitate its eccentric reaction, and then her reincarnation of Henry Springer, given as a drawing-room entertainment, became the choicest delight of a score of boon companions for long after the acquaintance with Mr. Springer had ceased.

“Should like to call on you—call, call, call,” said Henry. “Bring motor. Like a spin?”

“Very much indeed, Mr. Springer!” said guileful Ann Quigley.

Mr. Springer did call on Ann, and Ann went for a run in the motor with him. Ann was never selfish; if Henry Springer entertained her, she entertained Henry, and even while she was greedily seizing on the comedy elements of his own absurd character, she was giving him the benefit of her abilities and her humor.

“Good,” said Mr. Springer. “Good, good, good, very good. Yes, good. Yes, yes, yes, yes.”

Henry cackled a great deal. He seemed to be enjoying himself thoroughly.

“Never saw a girl like you,” he said. “Pon me soul never a girl like you. You do see the dem silliness in dem silly people. Yes, ah, ah. Yes, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha.”

Henry Springer had been at the house six times, the acquaintance was under three weeks old, when during that nice afternoon on the verandah, with Henry’s usual bouquet of roses on the floor beside Henry’s hat and gloves, he suddenly screwed his eyeglass in with more than usual resolution, and said:

“Marry!”

Henry’s head was back, his two arms were akimbo (plucked wings), and he was looking at her like a very old, pert and curious bird.

“Marry!” he repeated. “Marry, marry, marry, marry, marry.”

Then his excitement communicated itself to his defective leg, and it wriggled away to one side, as if seeking to detach itself. Henry let it have its way till the paroxysm was exhausted, then he restored it to its position, said “Ah-h-h!” and continued: “Marry, marry, marry. What say?”

“I—I don’t quite understand you, Mr. Springer,’’ said Ann, with downcast eyes and unimaginable simplicity.

“Marry,” said Henry. “Marry. Dem it, it’s easy. Marry, marry, marry. You will? Yes, yes, yes, yes.”

“This is so sudden, Mr. Springer,” said Ann, “so unexpected. You will have to give me time.”

“Time, time. Certainly, lots of time. Fellow’s still young, fellow’s still hearty.” Again the distressing leg wriggled away, and did a sort of rag on its own responsibility, and again it was restored. “Ah-h-h!” said Henry. “Say a week, a week, a week.”

“Or a fortnight,” said Ann. She saw her delightful acquaintanceship with Henry drawing to a close, and she hated to lose him.

“Right, right, right, a fortnight then, a fortnight. Two weeks, two weeks, weeks, weeks, weeks. Ah-h-h!” He grabbed his leg that time before it could get away on another convulsive excursion. “Ah-h-h! caught you,” he said.

“It’s a beastly shame,” Ann said to her mother that evening. “I know I shall never get another like him. I’ve half a mind to marry him after all.”

“Ann!” gasped her mother. “That old man? Marry him! You can’t possibly care for him.” Mrs. Quigley’s maternal eyes were round with apprehension.

“I don’t positively adore him,” said Ann, with an air of sadness, “but after all is true love everything? I’m sure I could be happy with Henry. I’ve only to look at that twittering leg of his, and my heart sings like a bird. I’m sure a girl could live happy with a leg like that—it’s such a gadabout.”

“Ann, don’t talk utter rubbish.”

“Still, mother, you must admit Mr. Springer offers many inducements. I might wait for ten years, and not get as funny a husband.”

“Bless my soul, girl! what reasonable creature wants a funny husband?”

“I don’t know, but it seems to me marriage would be quite bearable if one’s husband were funny enough. That’s why I’m thinking seriously of Mr. Springer.”

“Well, Ann Quigley, if you marry that wriggly old devil, I’ll never speak to you again.”

Ann had not the remotest idea of marrying Mr. Henry Springer, and Henry’s own intentions will have further light thrown on them, but meanwhile Mr. Springer was the twittering old gallant to the life. He literally embowered Ann in roses; the chocolates he bought were in huge, elaborate boxes, ornate enough to be conspicuous features in a swagger Chinese joss house, or a pantomime transformation scene.

“Fortnight, mind,” said Henry, “fortnight, fortnight. Two weeks, weeks, weeks.”

“I remember Henry,” said Ann demurely.

“Henry!” Mr. Springer exploded, “Henry! Called me Henry, Henry, Henry, Henry. By jove!” He seized her hand, he raised it towards his lips, with his other hand he removed his hat, holding it in a reverent attitude as one does at a burial, then he kissed Ann’s knuckles. It was a most impressive performance.

“Oh, Harry,” said Ann. “You’re a naughty, naughty boy.”

“Boy!” cried Henry. He laughed like the rustling of brown paper for nearly a minute. “Boy,” he cackled, “boy, boy, boy!” Here he was pulled up by an unfortunate spasm in the impertinent leg, and his rhapsody ended in a long-drawn “Ah-h-h!”

“Answer Sunday, Sunday, Sunday,” said Henry on leaving.

“I remember. You must come to dinner,” said Ann.

Henry Springer came on the Sunday evening. He was dressed with the utmost elaborateness, and he had crimped his hair. Never was his hat brim so curled, or his eyeglass so dazzling, or his boots so glittering, or his spats so spotless.

“The day,” he said, wagging a finger at Ann, “the day, the day, day, day, day.”

Ann detained him in the drawing-room for half-an-hour, and then Henry was led into dinner.

In the dining-room were Mr. and Mrs. Quigley, Ann’s sister Violet, and an old shrunken woman who sat nodding at the head of the table. The old woman had been very tall, now she was bent. She had much difficulty in keeping her chin out of her plate, and her head nodded strangely.

Ann took Henry by the hand, and brought him forward. There was some attempt at resistance on Mr. Springer’s part, and he was spluttering in an effort to articulate.

“Papa and Mamma,” said Ann, in affected speech. “Mr. Springer has promised to marry me.”

“Naughty Henry!” croaked the old lady at the head of the table.

“I have considered his proposal. He is a good man, papa. He loves me dearly, mamma. I don’t think I can find it in my heart to refuse him.”

“What’s all this!” stuttered Mr. Springer. “What’s all this, all this, all this, this, this?”

“Henry, I will marry you,” said Ann, and her arms went about Henry’s neck, her weight bore him down.

“No, I say, dem it,” cried Henry. “No, no, no. Not in the presence of one’s wife!”

“Your wife!” cried Ann.

“My wife,” said Henry. “Dem it all, Susan, what’re you doin’ here? What, what, what, what?”

“Good evening, Henry,” croaked the old lady.

“It’s a beastly trap, by jove,” said Henry. “A dooced ungentlemanly thing to do, dooced ungentlemanly, dooced ungentlemanly to introduce a fellow’s wife at such a time, time, time, time.”

“Naughty, naughty boy, Henry!” piped the ancient female.

“I’m going,” said Henry. “It’s a dashed insult. I-I-I-I”

His leg went back on him as he broke for the door, and he hit the jamb with his nose.

Mr. Quigley went after Mr. Springer, and Henry’s exit from the house was most undignified.

Of course it was Ann who had hunted Mrs. Springer’ out, and had arranged this dramatic finish for her two-act comedy. Ann is quite content with the denouement, and the farce has gone into her extensive repertoire.

“Henry is always marrying someone or another,” said the old lady as Ann parted with her that night. “I don’t often interfere with him now.”

Miss Jane Gaby was one of the many joys of Ann’s life. Miss Gaby was a professional lady, who came by the day, hiring out her services as a specialist at the moderate rate of four shillings and sixpence per diem.

Miss Gaby was a wonderful washer. You’d hardly have thought it to look at her, but appearances are proverbially deceitful. The fact is Miss Gaby bestowed so much soap and water and such excess of “elbow grease” upon other people’s goods she had little to spare for her own, consequently this expert cleanser was never quite clean.

I have heard it said that shoemakers’ children are always ill-shod. For the same reason, possibly, washerwomen are often ill-washed. Miss Jane Gaby, washerlady, was invariably ill-washed. She was small, she was sparse—so sparse, in fact, that she hadn’t flesh to spare for the adequate covering of her bones.

“She looks like a collapsed balloon filled with sticks,” said Ann Quigley.

That was fairly descriptive of Jane’s figure. Jane’s face was browned and toughened with much exercise over many copper fires, and by the wear and tear of wind and weather braved in the hanging out of untold washing.

Jane might have been twenty-eight, or forty-five, or anything in between. You realised, at any rate, she was no longer a girl, and you perceived from her ant-like energy when on the job that she was not hopelessly old. The rest was mere conjecture.

Jane Gaby came to “business” dressed up and carrying her working clothes in a string-bag.

“Don’t want ev’rybiddy t’ know yer bizness,” said Jane. “A washer and scrubber’s got ez much right t’ dress like a lydie ez a servinkt has, I sez.”

Ann Quigley applauded the sentiment. “Of course she has, Jane. Don’t let yourself down. Keep up appearances. Why shouldn’t you look elegant?”

Jane Gaby smoothed her little bit of fur. Originally that bit of fur was bear; now it was almost bare. It had been given to her by a generous mistress long, long ago. Jane called it a “tippet,” but it looked like an onion net that had unaccountably grown whiskers. “I thought I’d put on me furs this mornin’,” said Jane.

“Quite right, Jane,” said Ann demurely, her eyes twinkling. “Where’s the sense in keeping smart things stowed away for thieves to steal?”

“Or fer the moths to get at ’em,” said Jane. “Do you think me ’at’s too gay? Dinny sez it’s puttin’ on dorg.”

“Not a bit, Jane. I’d even put a few plums in if I had them.”

“To go with the cherries? Sorry I ain’t got any. I put in all the hartificial grapes an’ cherries I ’ad, an’ Mrs. Rogers gave me this wax happle.”

“All the fruits in season,” said Ann, solemnly,

“Yes, miss. Bein’ ez how fruit’s in, it orter be fash’nible in ’ats.”

Subsequently Miss Ann Quigley made a collection of artificial fruits for the further decoration of that hat. Jane’s hats were an undying delight to Ann. She begged old flowers and feathers from her friends to add to the marvels and mysteries of Miss Gaby’s hats, and Jane, poor simple soul, accepted all with the greatest gratitude, and added the lot to her headwear.

The present hat looked like an ordinary kitchen bowl with a close-curled rim, and Jane had sewn it liberally with mixed fruits, and very stale mixed fruits at that. Jane’s notions of hat trimming were unique in their simplicity. If she were trimming with feathers, she seized all the ill-used feathers in her large collection of “trimmings” and attached them to her tile. So, too, with fruits, flowers, or ribbons. You may gather what Jane’s large assortment of trimmings amounted to from her confidential report.

“I love t’ go scrubbin’ out where there’s bin a shiftin’, Miss Quigley,” she said. “You can get sich heaps iv trimmin’s. People movin’ acts ez if they was never a-goin’ t’ wear ’ats again.”

Ann, hovering in the steam, fishing for Jane’s confidences, preserved a face of preternatural gravity. “Yes,” she said sympathetically, “I’ve noticed you don’t go short of hats. None of my friends, some of them rich people, have such a variety.”

“I make it a pint never t’ go out three times runnin’ in the same ’at,” said Jane. “Why should I? I’m doin’ scrubbin’ fer three ’ouse an’ land agents —that means one empty ’ouse t’ scrub every week sometimes more, an’ every empty ’ouse has its ’at, often two. At one place last month I got three, an’ a ’ole harmful iv trimmin’s.”

“Lucky girl!” said Ann. Ann was externally composed—internally she was simmering with laughter.

“You know that bronze coat with the ostridge hair collar you was admirin’ lars’ Monday, Miss Quigley?” resumed Jane in a burst of confidence. “Well, I got that at a shiftin’. The larst tenant left it ’angin’ behind the kitchen door.”

“Me best boots, too—them pemellers—I got in a hempty ’ouse I ’ad to scrub out. Wonderful the things you can pick up in hempty ’ouses. Dinny sez: ‘Me girl, alwiz keep yer eyes open in a hempty ’ouse. I got him a ’ole new suit in a cupboard in a scrub-out once. ’Twas a bit worn on the edges, but he got five shillin’s fer it et a ’ole close shop.” Dinny was Jane’s young man. Jane had often spoken of him to Ann, and Ann was consumed with eagerness to behold the hero. Many a happy half-hour she had given to the work of pumping Jane for details of the life and adventures of Dinny Smith.

“You know, miss, Mr. Smith’s a gentleman,” said Jane.

“A gentleman?” interrogated Ann, with the expected air of happy surprise.

“Yes. You can’t get Dinny t’ do a single hand’s turn. A perfec’ gentleman, he is.”

“How nice!” said artful Ann. “But how does he live?”

“Oh, there’s alwiz counter lunches,” said Jane, “an’ mostly people is very good to him. He has such takin’ ways, Dinny has, an’ he’s so ’andsome an’ stylish scarcely anyone can refuse him anythink. He took me to the livid pickshers the other night. I wore me noo more-on-tick yer mother give me, an’ me fruit ’at; but ’twas all wasted, coz Dinny, he wouldn’t go in till the lights was out.”

“That was a pity, Jane. I’m sure you would look chic in that gown.”

“Shick, miss? I gi’ you my word, I ’adn’t tasted—”

“No, no, not ’shic’—chic, smart, you know.”

“Oh, I did. But it’s a curious thing Dinny never will go into them livid pickshers till the lights is out. He alwiz sez there’s someone in there might wanter borrer money off him. Dinny’s father was a great politician, you know, miss. Rang the bell at ’lection-eerin’ meetin’s, he did.”

There were many stories of Dinny’s escapades, and often Jane dwelt rapturously on his sheer manly beauty.

“Dresses like a torf, he does,” said Jane; “carries his stick with the best of ’em, and his watch-chain’s almost gold. He ain’t got a watch, but he sez he’ll ’ave one yet, an’ he will, too. Dinny gets everythink he sets his ’eart on.”

“When are you to be married, Jane?” asked Ann one day, as she stood in the steam of the wash-house, while Jane flogged a trough of soapy linen.

“I dunno yet,” Jane replied simply. “We’ve on’y bin engaged five years; but it won’t be long, I think, coz Dinny ’ates long engagements. He’s savin’ up fer it.”

“But if Mr. Smith will not work, how can he be saving up, Jane?”

“Oh, easy, miss—he’s savin’ up my money.”

“How kind of him. He must be a nice man. I wish I could see him.”

“It wouldn’t be no use, miss,” said Jane innocently, grimacing fiendishly over the wringing of a shirt. “There ain’t no woman in the world fer him but me.”

For a long time Ann Quigley had been delighting her friends with little bits of Jane Gaby, washerlady. Jane was one of Ann’s most popular impersonations, and Jane’s revelations, as translated by Ann, were certainly the most piquant comedy.

One day a young man of about twenty-eight, tallish, fairly well dressed and rather good-looking, after the raffish manner of a bookmaker’s amanuensis, entered by the Quigley’s back gate. He came upon Ann in the garden.

“Is Miss Gaby here?” he asked. “Might I see her for a minute?”

Jane and the young man conversed closely under an apple tree, and Ann, the rogue, from good cover, kept an eye on the pair. She saw Jane count some silver into the palm of the stranger, who then kissed the high angle of Jane’s left cheekbone in a perfunctory manner, and went away.

“That was ’im, miss,” said Jane.

“Mr. Dinny Smith—your intended?” exclaimed Ann. She was not able to wholly conceal her surprise this time.

“Yes, miss. Didn’t I tell you he was a gentleman? Oh, it ain’t on’y the lydies what can get a fine gent. Did yeh ever in yer life see anythin’ ’andsomer?”

“He is rather good-looking.”

“Nothing wrong with Dinny, there ain’t, bar that scar by his eye. He got that rescuin’ a fair lydie.”

“A fair lady? How romantic!”

“Yes. He rescued her from a policeman, an’ the cop ’it ’im with ’is stick. The fair lydie was drunk et the time.”

“He’s quite a hero.”

Ann Quigley had now her own suspicions of Mr. Dinny Smith, gentleman, and when she gave this new bit of Jane Gaby—the tale of the rescue of the fair lady, with a vivid description of the hero—Olivia Anderson uttered a cry.

“A scar,” she cried, “here by the eye, shaped like a triangle, a little ruddy brown moustache, black eyes! That’s Alfred Holmes, our Martha’s young man. Martha is our servant, you know. She’s fat and thirty-five. She’s awfully soft on Alfred, and he comes to see her—generally on pay night.”

“We’re getting warm,’’ said Ann. “I must investigate Dinny.”

About a fortnight later Ann had a great tale for her friends.

“I’ve found out all about Mr. Dinny Smith,” she said. “I asked Cooper, the detective, if he knew anything of such a man, and he knew him perfectly. ‘Now, miss, I wouldn’t expect you to have any dealings with a crook like Jessop,’ he said. I explained that I was merely curious about the blackguard. ‘Well,’ said Cooper, ‘he’s known as Genteel Jessop. He’s a cheap spieler. His best play is imposing upon silly women. For three years in Sydney he was kept, and well-kept, too, by a lot of servant girls scattered through the suburbs, to whom he’d engaged himself.

“There must have been twenty or thirty of them, and he bled them to the extent of about 10/- a week a-piece. I wouldn’t be surprised if he was at the same game here. Do you know anything, miss?’ Of course I didn’t. I didn’t want police interference to spoil my play.”

“But he is doing the same here,” cried Olivia. “He’s robbing our Martha, I’m sure.”

“Of course he is. And he is robbing poor old silly Jane; but there is something to be made out of this, and I want you girls to come along on Friday night. I’ve got an idea for a little al-fresco comedy. Olivia, you bring Dick. I shall have Billy Crowther. Meanwhile, keep it dark.”

Mrs. Quigley had engaged Jane’s services for a whole week for a special spring cleaning; but on the Friday evening Jane was unexpectedly liberated at 7 o’clock, and went off in her fruit hat and her bronze coat trimmed with “ostridge hair” to do the pictures.

Ann’s guests all arrived at the appointed time, and Ann, preserving a great mystery, disposed of them all in hiding in the big fruit garden at the back.

‘‘Don’t move, don’t speak,” said Ann. “If you do, you will spoil all.”

Ann left them there, and about ten minutes’ later a whistle was blown at the back gate. It was repeated twice before Jane Gaby appeared. Jane came down the moonlit garden path. There was no mistaking Jane’s peculiar, slip-shod walk, Jane’s peculiar figure caved in from the back, and, above all, Jane’s peculiar hat.

The gate opened, and Mr. Dinny Smith, alias Arthur Holmes, alias Genteel Jessop, went up the path to met her.

“Well, old dear,” he said, “where’s the gonce?”

“Yes not pertickler lovin’ t’night, Dinny, is yer?” said Jane, and there was no mistaking Jane’s quaint enunciation.

“Oh, cut the soft stuff, Skin,” said Mr. Smith. “Take this in passing.” He kissed Jane aimlessly, and it landed on her ear. “And please clean up the dibbs, I’m hasty.”

“I don’t think I orter give you any more money, Dinny.”

“You don’t think! Well, get your thinker going at once, and wish up five dollars or I stand out.”

“Wot! yid turn me down after all I done for yeh, after all the money yiv ’ad! Ev’ry penny I ever earned yiv ’ad, Dinny.”

“Of course I have, and isn’t it hung up where I can get it, safe and sound, accumulating interest. Thirty per cent. I’m getting on that money, and you’d stick it away in an old boot where it wouldn’t earn a bean.”

“I want it all back. I want it now, too. If you don’t gimme it I’ll call the p’lice.” Jane had seized him by the coat.

“You’ll what?”

“I’ll have the cops on yeh. They’re ’andy, waitin’. Gimme me money.”

Mr. Smith was perturbed. “Here Jane, old dear, don’t be a nark,” he said. “I haven’t got a bean on me; but you’ll get your stuff all right.”

“I don’t b’lieve it. I ’eard all about you, Mister Harther ’Olmes, Mr. Genteel Jessop, doin’in poor girls fer their earnin’s. You done me in, an’ I ain’t going t’ let you off too easy. Take that, yeh dirty robber!” Jane produced a pot-stick from under her coat, and it cracked on Mr. Smith’s occiput, Mr. Smith went down. “Take that,” said Jane, “an’ that, an’ that, an’ don’t you never come near again, ’r Mister Detective Cooper ’ll stick you in gaol fer seven years. I’ve torked t’ ’im about you, yeh dirty, loafin’ ’ound! Take that!”

Mr. Dinny Smith was going on hands and knees towards the gate, and Jane was beating him lustily as he went. He tore at the latch under a rain of blows, and as he fled into the right-of-way the pot-stick, thrown with great spirit, took him between the shoulder-blades.

Mr. Dinny Smith had gone out of Jane Gaby’s life for good and all, and Jane, after shrilling a few objurgations in the wake of the villain of the piece, went shuffling back towards the house. Ann’s guests trooped after her; but Jane fled into the apartments temporarily set apart for her, and the others passed on to the drawing-room in silence, respecting her sorrow.

Ann joined her friends a few minutes later. Ann was flushed and breathless, but otherwise undisturbed.

“Well,” she said, “did you enjoy the performance?”

“It was ripping,’ said Billy. “Didn’t the old girl dealt it out to him.”

“She did,” Ann grinned wickedly. “But now we must keep all this from Jane, or she might spoil the good work.”

“Keep it from Jane?” gasped Sylvia. “Why—who—what—”

Ann fell into a Jane attitude—Ann assumed the Jane voice. “With the help of a few properties I was the avenging angel,” she said.

Then the laughter began in earnest. It had not quite died away when the real Jane Gaby returned gaily from the “livid pickshers” nearly two hours later.

“Beautiful!” said Ann. “Lovely,” she said. Oh, and that ruby set! Isn’t it sweet?”

Ann was enraptured as Mrs. Shoppie lifted article after article from the crystal case in which her jewels were contained.

“But, aren’t you afraid of thieves, dear?” said Ann anxiously.

“Not in the least,” replied her friend. “Thieves don’t break into a simple, uncompromising little cottage like mine on spec, and nobody knows about my jewels excepting my friends, none of whom appear to be sufficiently covetous to be tempted to burglary.”

“If I had all these,” said Ann enviously, “I’d want to load myself down with the whole display, and flash myself upon a first-night audience at the theatre—a veritable blaze of glory.”

“Like a Queen of Sheba,” smiled Mrs. Shoppie.

“Or a chandelier,” replied Ann.

“I love jewellery, dear, but I never wear it. I take the interest in nice jewels that a philatelist takes in rare old stamps.”

“That’s funny,” Ann said regretfully. “I would as soon think of collecting oysters, or fricasseed crayfish, or roast pigeons for the pleasure of feasting my eyes on them.”

“If I were in the habit of wearing them I certainly would be fearful of keeping them about the house,” the widow said.

“They must be worth hundreds,” sighed Ann.

“I would not take a thousand pounds for this and its contents.” Mrs. Shoppie held up the crystal casket and its glittering contents in her small plump hands.

Mrs. Shoppie’s hands were her most attractive attribute, neat and white. They were the hands of a girl of sixteen, whereas the widow was forty-five, a little too heavy for her height, her full cheeks a little too red, her dark hair already grained with silver. But there were no rings on her fingers, her full, rather short neck was guiltless of jewels, and her tiny ears were unadorned with gems.

Ann had a sumptuous taste for jewellery. Her own round arms displayed bracelets and bangles, and about her white neck was laced a long chain of round beads, almost gold.

“I’m brummy, and Sis is brummy,” said Ann sadly, in reference to these adornments: “but with industrious polishing I hope to pass the family paste off as the genuine thing, and here are you hoarding up hundreds and hundreds of pounds’ worth of the real goods, just for the satisfaction of feasting your eyes on them once in a way. You are an undeserving wretch; you are unfit to possess these blessings of Providence.”

Mrs. Shoppie held up a string of pearls. “Beware, woman!” said Ann Quigley, scowling in the manner of the dark and lustrous adventuress in the melodrama. “Do not tempt me too far. I could inbrue my hands in gore for less than this!”

The widow Shoppie was a new acquaintance of Ann’s. Our Miss Quigley had an amazing faculty for making friends, especially among women. Ann was unique in this—that, although most men were ready to make love to her, all women were prepared to be friendly with her. Cynics have said it is impossible for women to like the women men love. But women did like Ann, and certainly the masculine elements were always propitious.

There was something in Ann’s humor that appealed most directly to her erring sisters. For the delectation of one woman she could closely imitate all the peculiarities (facial and fanciful) of all her best friends, and with a touch of caricature that made them grotesque. We might dwell on the notion that this manifests the peculiar cattishness of women, were it not for the lamentable fact that man is equally unworthy, and rejoices just as keenly in the misfortunes of his best friend, as enlarged by the caricaturist or the comedian.

Mrs. Shoppie had taken to Ann spontaneously. “You are like champagne, dear,” she said. “I love champagne, but it gives me a deplorable head. You stimulate me, and don’t give me a head. You must come and see me, and do that bit of old Mrs. Crowther all over again just for me. Do, do. I must get even with old Mrs. Crowther. She has bored me to extinction a score of times, and to be able to sit and laugh right out at her as you act her (and you do her to the life, dear), is such a comfort, you really wouldn’t believe.”

Ann was just as ready to make friends, and here she was in the widow’s little home, a free recipient of the widow’s confidences, be-deared, and kissed, and applauded, possessed of the story of the widow’s life —an old and valued bosom friend of fifty-two hours’ standing.

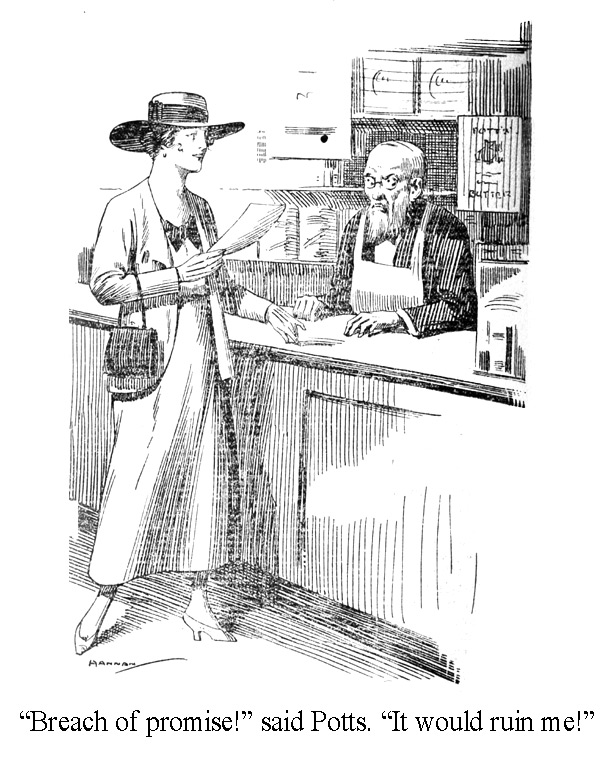

The two had dined together. It was a delightful little dinner Mrs. Shoppie provided.